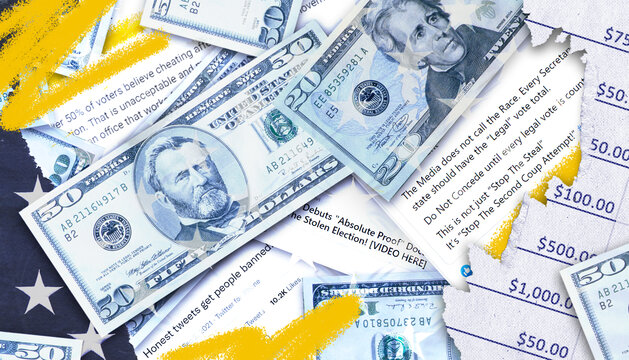

Across the country, states are holding elections for offices like secretary of state that will play key roles in running the 2024 elections. In many states, the parties’ nominees are known, and the general election is already underway. These races are attracting far more attention this year than in recent memory. Part of the reason for the increasing visibility of election officials is the spread of the Big Lie that voter fraud “stole” the 2020 race from President Trump. In state after state, campaigns focus on election denial as a central issue.

In this series, the Brennan Center examines the finances and political messages in contests that are important to the future of election administration. Throughout 2022, we regularly look at relevant contests in battleground states that had the closest results in the 2020 presidential election. As candidates file disclosure forms and information becomes available, we examine questions such as how much money is raised, who the biggest donors are, and how much outside spenders, like super PACs and dark money groups, spend.

Here are some of our newest key findings:

- Across six states with a secretary of state election this year, fundraising by candidates has totaled $16.3 million, more than double that raised by an analogous point in 2018. The biggest increase is in Nevada, where candidates have raised $2.6 million — more than five times the last cycle.

- Out-of-state money is rising as well, showing that the increase is not coming only from constituents of these state offices. Arizona has seen the largest boom in money from other states, almost four times more than in 2018.

- Across all six states, 12 election denial candidates have together raised $7.3 million. That’s less than the $8.1 million collected altogether by the 10 candidates who have taken a stance against election denial — most of which was raised by incumbents, who have an inherent fundraising advantage. Without incumbents, the six remaining opponents of election denial have together raised $4 million.

- Outside spenders are active in secretary of state races, in which super PACs and dark money groups have spent at least $8.8 million, with $5.6 million in Arizona alone. While some of this spending pushes election denial messages, most of what we have found opposes election denial candidates and appears to be funded by traditional Republican groups or liberal organizers, including labor. We have also seen outside spending involving election denial in local races in Nevada and Wisconsin.

- Prominent election deniers have attracted large donations — often the legal maximum — from donors who are active in multiple states. Several prominent donors have ties to the January 6 insurrection and other challenges to the 2020 election result, including former Overstock CEO Patrick Byrne, construction software CEO Michael Rydin, and packing supplies magnate Richard Uihlein. Most of the donors we identified had not given to secretary of state candidates before this election.

At this point in the primary season, the November ballot is set for races for governor or secretary of state in several states in our sample, and election denial candidates have seen mixed results. Election deniers advanced in seven of the ten contests for statewide office where parties have either held a primary or endorsed a presumptive nominee. In the coming months, there will be six more primary elections in four states where election deniers are running for statewide office.

In Georgia, incumbents beat back challenges from election denialists in Republican primaries for governor and secretary of state. Michigan’s state Republican Party has endorsed an election denier for secretary of state, who will face the incumbent in November. In Minnesota, the GOP has endorsed election deniers for both governor and secretary of state. Nevada’s Republican gubernatorial nominee has acknowledged that Biden won, although he has questioned whether it was “fair and square,” and an election denier won the primary for Nevada secretary of state. Republican gubernatorial nominees in Florida and Pennsylvania have cast doubt on the 2020 election.

In addition, a number of local races we are tracking have seen election deniers advance to the general election. Election deniers will be on the November ballot in multiple Nevada counties, including challengers who beat their own party’s incumbent in Storey County and Washoe County. And voters in Travis County, Texas, will see an election denier on the ballot in November.

These trends are not unique to our sample of battleground states, of course. There will be at least 120 election deniers on general election ballots in federal and state races this year.

Some candidates who lost primaries this year have used election denial narratives to claim their own losses were illegitimate. Joey Gilbert, defeated in the Republican gubernatorial primary in Nevada by approximately 26,000 votes, said after the race was called, “I will concede nothing.” He also claimed that there were several violations of election law in the primary. In July, he filed a lawsuit contesting the result. The suit claims that the reported result violates mathematical laws that govern the ratio between mail, early, and Election Day vote totals — claims similar to debunked arguments about 2020. The suit claims votes for Gilbert in the Republican primary were somehow transferred to the incumbent running in the Democratic primary.

The phenomenon is not limited to the battleground states in our sample.Tina Peters (R) lost her primary bid for Colorado secretary of state by 88,000 votes after a campaign in which she questioned the 2020 results and defended herself against criminal charges that, as clerk of Mesa County, she allowed unauthorized access to election systems. When her race was called, Peters said, “We didn’t lose, we just found evidence of more fraud . . . they’re cheating and we’ll prove it once again.”

At least one candidate has turned denying the legitimacy of his loss into fundraising success. Joe Dill lost the Republican primary for a county council seat in Greenville County, South Carolina, and sought to overturn the result by pointing to “irregularities” like voters being told to vote in precincts other than where they live and problems with voting machine calibration. Dill raised 66 percent of his funding for the cycle — $7,665 — after the June 14 primary.

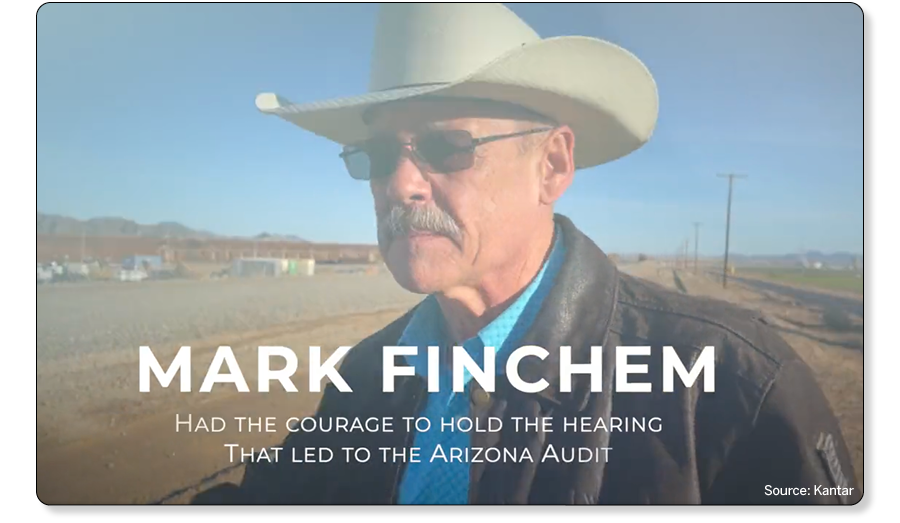

Even without a loss, some candidates are making claims of election fraud in this year’s primaries. The winner of the Nevada GOP primary for secretary of state, Jim Marchant, expressed doubts about the June election, saying there were “anomalies — malicious or accidental,” and “I’m surprised that I won.” And in Arizona, candidates have suggested that the upcoming primary will be tainted. Gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake (R) said a primary opponent “might be trying to set the stage for another steal.” Mark Finchem (R), running for secretary of state, said in June: “Ain’t gonna be no concession speech coming from this guy. I’m going to demand a 100 percent hand count if there’s the slightest hint that there’s an impropriety.”

This week, Arizona and Michigan hold primaries that will determine nominees for governor or secretary of state. Next week, on August 9, there will be primaries in Minnesota and Wisconsin.