The early 2020s will likely be remembered as the beginning of the deepfake era in elections. Generative artificial intelligence now has the capability to convincingly imitate elected leaders and other public figures. AI tools can synthesize audio in any person’s voice and generate realistic images and videos of almost anyone doing anything — content that can then be amplified using other AI tools, like chatbots. The proliferation of deepfakes and similar content poses particular challenges to the functioning of democracies because such communications can deprive the public of the accurate information it needs to make informed decisions in elections.

Recent months have seen deepfakes used repeatedly to deceive the public about statements and actions taken by political leaders. Specious content can be especially dangerous in the lead-up to an election, when time is short to debunk it before voters go to the polls. In the days before Slovakia’s October 2023 election, deepfake audio recordings that seemed to depict Michal Šimečka, leader of the pro-Western Progressive Slovakia party, talking about rigging the election and doubling the price of beer went viral on social media.

Other deepfake audios that made the rounds just before the election included disclaimers that they were generated by AI, but the disclaimers did not appear until 15 seconds into the 20-second clips. At least one researcher has argued that this timing was a deliberate attempt to deceive listeners. Šimečka’s party ended up losing a close election to the pro-Kremlin opposition, and some commenters speculated that these late-circulating deepfakes affected the final vote.

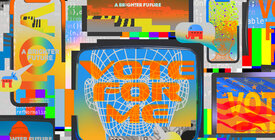

In the United States, the 2024 election is still a year away, but Republican primary candidates are already using AI in campaign advertisements. Most famously, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’s campaign released AI-generated images of former President Donald Trump embracing Anthony Fauci, who has become a lightning rod among Republican primary voters because of the Covid-19 mitigation policies he advocated.

Given the astonishing speed at which deepfakes and other synthetic media (that is, media created or modified by automated means, including with AI) have developed over just the past year, we can expect even more sophisticated deceptive communications to make their way into political contests in the coming months and years. In response to this evolving threat, members of Congress and state legislators across the country have proposed legislation to regulate AI.

As of this writing, federal lawmakers from both parties have introduced at least four bills specifically targeting the use of deepfakes and other manipulated content in federal elections and at least four others that address such content more broadly. At the state level, new laws banning or otherwise restricting deepfakes and other deceptive media in election advertisements and political messages have passed in recent years in states as ideologically diverse as California, Minnesota, Texas, and Washington. Federal and state regulators may also take action. Recently, for example, the advocacy group Public Citizen petitioned the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to amend its regulations to prohibit the use of deepfakes by candidates in certain circumstances.

However, even as policymakers move to update laws and regulations in the face of new and more advanced types of manipulated media, they must be mindful of countervailing considerations. Most important among these considerations is the reality that manipulated content can sometimes serve legitimate, nondeceptive purposes, such as the creation of satire or other forms of commentary or art. These types of expression have inherent value and, in the United States, merit considerable legal protection under the First Amendment. U.S. law specifies that even outright deception with no redeeming artistic or other licit purpose, while typically entitled to less constitutional protection, cannot be prohibited simply for its own sake. The government must still provide an independent justification for any restriction and demonstrate that the restriction in question is appropriately tailored to its stated goal.

These constraints are not a reason to shy away from enacting new rules for manipulated media, but in pursuing such regulation, policymakers should be sure to have clear and well-articulated objectives. Further, they should carefully craft new rules to achieve those objectives without unduly burdening other expression.

Part I of this resource defines the terms deepfake, synthetic media, and manipulated media in more detail. Part II sets forth some necessary considerations for policymakers, specifically:

- The most plausible rationales for regulating deepfakes and other manipulated media when used in the political arena. In general, the necessity of promoting an informed electorate and the need to safeguard the overall integrity of the electoral process are among the most compelling rationales for regulating manipulated media in the political space.

- The types of communications that should be regulated. Regulations should reach synthetic images and audio as well as video. Policymakers should focus on curbing or otherwise limiting depictions of events or statements that did not actually occur, especially those appearing in paid campaign ads and certain other categories of paid advertising or otherwise widely disseminated communications. All new rules should have clear carve-outs for parody, news media stories, and potentially other types of protected speech.

- How such media should be regulated. Transparency rules — for example, rules requiring a manipulated image or audio recording to be clearly labeled as artificial and not a portrayal of real events — will usually be easiest to defend in court. Transparency will not always be enough, however; lawmakers should also consider outright bans of certain categories of manipulated media, such as deceptive audio and visual material seeking to mislead people about the time, place, and manner of voting.

- Who regulations should target. Both bans and less burdensome transparency requirements should primarily target those who create or disseminate deceptive media, although regulation of the platforms used to transmit deepfakes may also make sense.