The November 2020 election has been called the “most secure in American history” by the federal government’s cybersecurity agency. This is good news that all Americans should celebrate, but it does not mean the work to protect our elections is done. Election security is a race without a finish line. 2020 offers important lessons for how to protect future elections from cyberattacks and technical failures. We detail five of them below.

Preparation is key to election security

While there were reports of malicious activity from foreign actors in the weeks leading up to Election Day, we avoided the type of debilitating attack that many experts feared. This was not just good fortune. After a wake-up call in 2016 — when Russian agents engaged in extensive probing of the country’s election infrastructure — election officials worked with federal authorities and security experts to understand vulnerabilities in their systems, upgrade infrastructure, invest in training and technical support, and put in place backup measures to recover from technical failures.

Greater collaboration between the federal government and state and local election authorities represented one of the most critical areas of progress. In January 2017, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) designated the nation’s election systems as “critical infrastructure.” Since then, federal agencies like the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) have stepped up to increase information sharing, support, and resources to help election officials understand and meet the challenges of cybersecurity. The agency deployed intrusion detection sensors on election related systems, conducted risk and vulnerability assessments, and helped train election officials on cybersecurity best practices.

Attacks against our elections didn’t stop after 2016. But we are now better prepared to defend ourselves against these intrusions. As former deputy director of CISA Matt Davis noted, “there were intrusion attempts and other kinds of mischief on election day [in 2020],” but states were “better prepared” and were able to “[bat] them down” before they caused any harm.

While our investment and preparation paid off this year, threats will evolve and that means our defenses must too. Recent reports that Russian government hackers breached Treasury and Commerce Department networks — and possibly those of other federal agencies — are a wake-up call that we still have much work to strengthen cybersecurity nationally.

What more can be done to protect our election infrastructure in the coming years?

Most importantly, Congress must make a long-term commitment to funding election security. Before 2018, Congress had not appropriated funds for elections since the Help America Vote Act passed in 2002. Since 2018, Congress has invested $805 million to secure our elections. While this funding helped states put themselves in a much stronger position to face cybersecurity threats in 2020, onetime investments without the certainty of continued funding can mean that important investments are never made. Indeed, election officials are often wary of implementing systems and processes that require long-term maintenance for fear that they will be left to pick up the tab once federal funds run out. Sustained federal funding would allow officials to create programs with longevity in mind.

Election security promotes voter access, and voter access promotes security

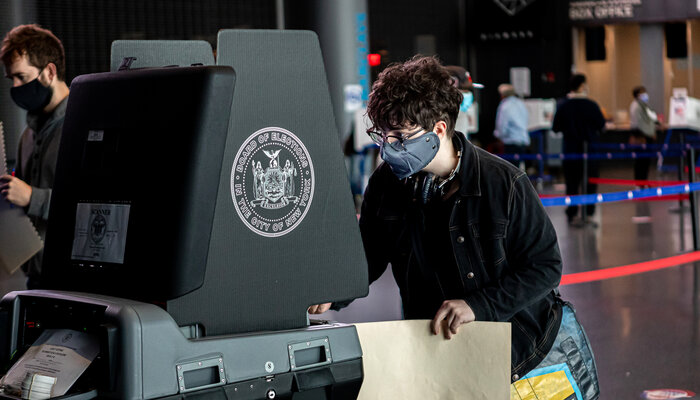

Election security improvements not only made our elections more resilient, but also had the welcomed effect of increasing voter access. Strengthened infrastructure meant that when government offices closed due to Covid-19, upgraded election websites were equipped to handle the increased demand caused by voters shifting to online registration. And when voters showed up to their polling places, recently upgraded voting machines were less likely to malfunction and cause voters to wait in long lines.

Election officials also prepared for a potential cyberattack by supplying polling places with paper-based backups. While we didn’t see a cyberattack shut down equipment this year, these contingency plans meant that voting could continue on Election Day during routine technical glitches. This fall, election workers in Fulton County, Georgia, provided voters with emergency paper ballots when voting equipment was slow to start; Franklin County, Ohio, switched to paper backup pollbooks when electronic pollbooks malfunctioned; and voters in Chesterfield County, Virginia, had the option to vote on provisional ballots when the state’s voter registration database became inaccessible during early voting.

Critically, the spillover benefits worked both ways in 2020: not only did efforts to strengthen election security promote voter access, but increased voter access in turn promoted security and resiliency. In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, states expanded access to mail voting, extended early in-person voting periods, and opened early more locations. These efforts paid off, as states saw record levels of early and mail voting.

More voting options meant that the impact and stress on election systems was spread out over a longer period and that there were more opportunities to discover and resolve issues before the end of the voting period. For instance, after overwhelmed electronic pollbook systems drastically slowed voting during the start of early voting in Georgia, the secretary of state’s office worked with the vendor and resolved the issue by the third day of early voting. Record-setting early voting meant that challenges that might have otherwise appeared for the first time on Election Day were detected earlier, when there was still time to fix them before most voters had cast their ballots. In states like Georgia, voters that showed up to the polls on Election Day experienced shorter wait times than they had in previous elections.

Congress failed in its obligation to adequately fund the 2020 election

When the pandemic reached the United States back in March, the Brennan Center estimated that election officials would face about $2 billion in extra costs to take the steps necessary to hold safe and secure elections in November (and up to $4 billion for all elections in 2020). That was on top of the normal costs of election administration that would exist even without a public health crisis. But states received just a fraction of that amount from Congress.

So how did election officials manage? In part by relying on private actors to fill the gaps left by policymakers. This included a $400 million contribution from Mark Zuckerberg — an amount equal to what Congress contributed — to fund election administration grants in more than 2,500 jurisdictions across the country.

And Zuckerberg was not the only private contributor to elections this year. The Schwarzenegger Institute at the University of Southern California distributed more than $2.5 million in grant funding for activities such as hiring additional election workers and keeping polling places open, according to the institute. NBA owners opened up their stadiums for free use as polling places or canvassing facilities. A coalition of businesses led by Business for America and the National Election Defense Coalition donated PPE and other critical supplies to polling places. Numerous businesses and nonprofit organizations took on the role of public education to help voters navigate their safe voting options this year and ensure that their ballot would be counted.

Further, hundreds of thousands of individuals stepped up to become first time poll workers in place of high-risk individuals, even when jurisdictions were unable to provide hazard or increased incentive pay for this work. Through initiatives like Time to Vote, private companies aided these efforts by paying employees who took Election Day off to work as poll workers.

To understand what November could have looked like without these volunteer and charitable efforts, we only need look at the primary elections from earlier in the year. Before additional assistance arrived, voters across the country dealt with polling place closures, fewer early voting opportunities, long lines, and mail ballot delays that led to their vote not being counted. All of these issues occurred when most states experienced turnout that was less than half of the record breaking activity we saw for the general election.

Absent a once in a lifetime pandemic, it is not at all clear the private actors will again jump into the void to ensure local jurisdictions can run their elections. And even if they are willing, it is a dangerous game to force jurisdictions to become reliant on private actors to be able to perform the most basic function of ensuring free and fair elections for all Americans. In a democracy, running and paying for elections is a core governmental responsibility. Congress must make sure that jurisdictions have the funds they need to run their elections going forward.

Paper ballots are necessary to secure voting equipment and build public confidence

Few aspects of our election system have received as much attention and ire from security experts as paperless voting machines. These machines pose a significant risk to election integrity: if election officials were to discover a hack of these machines, paperless systems provide no independent record that can be used to verify their accuracy.

States have prioritized the replacement of antiquated paperless voting machines over the past four years. In 2016, 14 states used paperless voting machines as the primary equipment in at least some of their counties and towns. Eight states have since replaced these machines, and the states that didn’t still saw more votes on paper ballots that in the previous election due to increased absentee voting.

The broad availability of paper records is one reason that former CISA director Chris Krebs said that this year’s election was our most secure ever. He noted that 95 percent of the ballots cast had a paper record associated with it in 2020, compared to only 82 percent of ballots cast in the 2016 election.

Even when a hack does not occur, election officials can increase confidence in election results by checking the paper records during an audit after the election. Within a week of Election Day, Georgia conducted a statewide audit of paper ballots, a historic first for the state, which reaffirmed the outcome of the presidential race as originally reported. Arizona, Nevada, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin — battleground states where partisans have questioned the validity of results without evidence — all have paper records and will conduct postelection audits.

But while there’s been a lot of progress in getting rid of paperless machines since 2016, six states still don’t have a paper record for every vote. In 2019, the Brennan Center found that many election officials wanted to replace their equipment before the 2020 elections but did not have the funds to do so.

Election administration is increasingly reliant on private vendors who face little oversight and accountability

Cyberattacks are not the only cause of technical failures. Whether the source of a failure is malicious or not, the impact on voters can be the same: making it difficult or impossible to cast a valid ballot. This year we once again saw problems with voting equipment, demonstrating the need for more robust standards for election systems. But the most common technical problems we saw came from electronic pollbooks used to check in voters, for which there are currently no federal standards.

Many of these electronic pollbooks were manufactured by a single vendor, a stark reminder of how widespread problem can become when there are issues with just one product or provider.

Private vendors play a critical role in every aspect of our elections. This was more apparent than ever in 2020, as election officials depended on private vendors to adjust their systems and meet the challenges of Covid-19. Most of these vendors came through. But some jurisdictions saw problems with voters receiving the wrong ballots, ballot tracking systems malfunctioning, and ballot printers backing out of obligations.

Election vendors face little federal oversight. Unlike in comparable critical infrastructures sectors, election system vendors are under no obligation to disclose ownership, report cybersecurity incidents, practice secure hiring practices, or ensure supply chain integrity. Because of this, state and local election officials often have no independent source to assist them as they outsource critical election work.

Congress must play a more aggressive oversight role in this space and ensure that vendors are taking the steps necessary to mitigate security risks.

It’s possible to make the next election even more secure. The key is to learn from the last one, keep investing in infrastructure, and build off the progress we’ve made.