A New Framework for Election Vendor Oversight

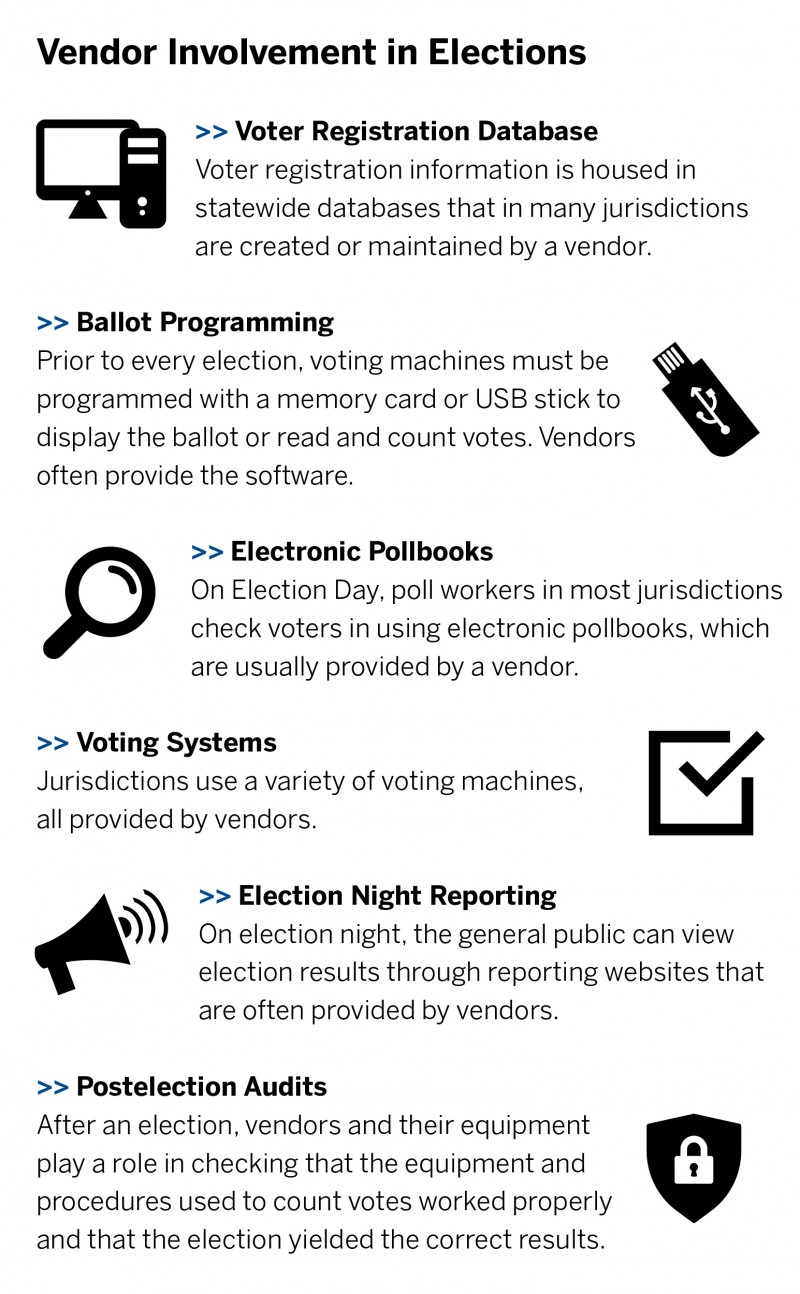

Under the Brennan Center’s proposal, the Election Assistance Commission’s oversight role would be substantially expanded. Oversight would extend beyond voting equipment to election vendors themselves. The current voting system testing is intentionally quite limited: it occurs at the end of the design, development, and manufacture of voting system equipment. It does not ensure that the vendors have engaged in best supply chain or cybersecurity practices when developing equipment or when servicing or programming it once it is certified. Nor does the system ensure that the vendor has conducted background checks on employees or set up controls limiting access to sensitive information.

Despite its limitations, the EAC’s Testing and Certification Program — a voluntary program that certifies and decertifies voting system hardware and software — provides a good template for a vendor oversight program. A variety of bills, including the Election Security Assistance Act proposed by Rep. Rodney Davis (R–IL) and the Democratic-sponsored SAFE Act and For the People Act, have called for electronic pollbooks, which are not currently considered voting systems and covered by the program, to be included in its hardware and software testing regime.

Currently, the Technical Guidelines Development Committee, a committee of experts appointed jointly by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the EAC, sets certification standards for voting systems. These guidelines, known as the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSG), can be adopted, with modifications, by a majority of EAC commissioners. Once approved, they become the standards against which voting machines are tested for federal certification. The VVSG ensures that voting systems have the basic functionality, accessibility, and security capabilities required by the Help America Vote Act (HAVA).

Future iterations of the VVSG and certification process may change slightly: commissioners have suggested that they may support a new version of the VVSG that adopts high-level principles and guidelines for the commission to approve, along with a more granular set of certification requirements, which staff could adjust from time to time.

Once new voting system guidelines are adopted, the EAC’s Testing and Certification Division tests the systems (per the VVSG), certifies them, monitors them, and, if critical problems are later discovered, decertifies them. The EAC conducts field tests of voting machines only if invited or given permission by a state election official. It does not do this on a routine basis. Rather, election officials using the certified voting machines have the option to report system anomalies to the EAC. If the EAC deems a report credible, it may begin a formal investigation and work with the vendor to address the problem. If the vendor fails to fix the anomaly, the EAC is obligated to decertify the voting system.

With some important modifications, we recommend a similar regime for certifying election system vendors. The commissioners should adopt a set of principles and guidelines for vendors recommended by a Technical Guidelines Development Committee, as well as a more detailed set of requirements that could be adjusted as needed by EAC staff. We recommend that the EAC routinely monitor certified vendors to ensure ongoing compliance and establish a process for addressing violations of federal standards, including through decertification.

A Voluntary Regime

Federal certification will only be meaningful if state and local governments that contract with election system vendors rely on it when making purchasing decisions.

For this reason, some have recommended that state and local governments be required to use only vendors that have been federally certified. For instance, the Election Vendor Security Act proposes that state and local election administrators be banned from using any vendor for federal elections that does not meet some minimum standards.

There are obvious benefits to a mandatory regime. Most important, it would ensure that all jurisdictions throughout the country use vendors that have met minimum security standards. But there are drawbacks as well. Not least of these is that some states and localities might view a federal mandate to use certain vendors as a usurpation of their power to oversee their own elections, making the creation of a federal program politically challenging.

Moreover, since private vendors are so deeply entwined in the running of our elections, requiring towns, counties, and states to use only certified vendors could present problems. If a vendor failed the certification process (or decided not to apply for certification), some counties would not be able to run their elections. Others might be forced to spend tens of millions of dollars to purchase new equipment and services before they could run elections again, even if they had determined that they could have run their elections securely.

A voluntary approach — leaving it to the states and local jurisdictions to decide whether to contract with non–federally certified vendors — could draw states into the voting system certification process. It may also be more politically feasible. A voluntary approach would give state and local jurisdictions the flexibility to take additional security measures if their current vendors did not obtain federal certification. In selecting new vendors, most states and local election officials would likely rely on federal certification in making purchases, as they do with voting machines. Democrats in Congress opted for this approach in the For the People Act and the SAFE Act. Both measures would incentivize participation by providing grants to states that acquire goods and services from qualified election infrastructure vendors or implement other voting system security improvements.

The drawback of a voluntary program is that states and vendors may ignore it. But there is reason to believe that there would be wide participation in a voluntary federal program. Even though the current voting machine certification program is voluntary, 47 of 50 states rely on the EAC’s certification process for voting machines in some way. Another voluntary program, DHS’s Election Infrastructure Sector Coordinating Council, was founded in 2018 to share information among election system vendors. Numerous major election vendors have supported it as organizing members.

Guidelines Developed by an Empowered, More Technical Committee

A new Technical Guidelines Development Committee, with additional cybersecurity experts, should be charged with crafting vendor certification guidelines for use by the Election Assistance Commission, incorporating best practices that election vendors must meet. These guidelines should go into effect unless the EAC overrides the recommendation within a specified period of time. This deference to the technically expert TGDC in the absence of an override by policymakers is necessary to avoid the kinds of lengthy delays that have stood in the way of prior attempts to update the VVSG. The NIST cybersecurity framework should be the starting point for these best practices, and the TGDC need only apply election-specific refinements to this existing framework.

The TGDC is chaired by the director of the NIST. Its 14 other members are appointed jointly by the director and the EAC. We recommend that Congress authorize NIST to expand TGDC’s membership to include the wider range of expertise necessary to fulfill its role in defining vendor best practices. These new members should explicitly be required to have cybersecurity expertise. Congress should also mandate that a representative from the new DHS Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), a leading voice in cybersecurity defense, including in the elections sector, join the TGDC. The Vendor System Cyber Security Act of 2019, introduced by Sen. Gary Peters (D–MI), would require this step. Similarly, Congress should mandate the inclusion of a representative from the National Association of State Chief Information Officers (NACIO) with expertise in cybersecurity.

Reconstituting the TGDC in this manner would not only ensure that it has the relevant expertise to set guidelines for vendors but also that there are more members with technical backgrounds.

As noted above, we recommend permitting the guidelines developed by the TGDC to take effect in the event that the EAC fails to act on them within a specified time period. We also recommend that vendors seeking certification must always meet the most recent set of guidelines. This, along with the expanded membership of the TGDC, will provide the necessary assurance that best practices are updated in a timely fashion and that vendors seeking certification meet the most up-to-date standards.

The new TGDC will be responsible for developing federal certification guidelines that vendors must satisfy to sell key election infrastructure and services for use in federal elections. Areas that should be covered in such guidelines include

- cybersecurity best practices,

- background checks and other security measures for personnel,

- transparent ownership,

- processes for reporting cyber incidents, and

- supply chain integrity.

Below, we discuss the importance of each of these items, what guidelines in each of these areas could look like, and how to ensure compliance.

Cybersecurity Best Practices

The lead-up to the 2016 presidential election provided numerous examples of the devastating consequences of failing to heed cybersecurity best practices. Through a series of attacks that included spearphishing emails, Russian hackers gained access to internal communications of the Democratic National Committee (DNC). The DNC reportedly did not install a “robust set of monitoring tools” to identify and isolate spearphishing emails on its network until April 2016, which, in retrospect, was far too late. The chairman of Hillary Clinton’s campaign, John Podesta, fell prey to a similar attack. These threats did not end in 2016; in the run-up to the 2018 elections, hackers targeted congressional candidates including Sen. Claire McCaskill (D–MO) and Hans Keirstead, who ran in a Democratic Party primary in California.

Guarding against spearphishing emails is Cybersecurity 101. Yet the numerous reports of successful spearphishing attacks suggest that many individuals and organizations fail to meet even that low bar of cyber readiness. Are vendors guarding against these (and other) attacks? Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report on 2016 election interference indicates that an employee at an election vendor fell victim to a spearphishing attack, enabling malware to be installed on that vendor’s network. The vendor, which many assume is VR Systems, has denied that that the attackers were able to breach its system. Under the current regime, which lacks any meaningful visibility into vendors’ cybersecurity practices, we simply do not, and cannot, know.

The new Technical Guidelines Development Committee should craft cybersecurity best practices that include not only equipment- and service-related offerings but also internal information technology practices, cyber hygiene, data access controls, and the like. Various bills have proposed that the TGDC take on this role, including the SAFE Act, the Election Security Act, and the For the People Act.

Vulnerability to attacks by insiders is a threat separate and apart from a hack over the internet.

The NIST Cybersecurity Framework should be the starting point and be supplemented by election-specific refinements. NIST advises that “the Framework should not be implemented as an un-customized checklist or a one-size-fits-all approach for all critical infrastructure organizations. . . . [It] should be customized by different sectors and individual organizations to best suit their risks, situations, and needs.”

When seeking Election Assistance Commission certification, vendors should have to demonstrate that they meet the TGDC’s cybersecurity best practices. The EAC should consider providing a self-assessment handbook or other form of guidance to facilitate vendor compliance with this requirement.

Such a self-assessment handbook exists in the defense sector for contractors that handle certain sensitive information. Department of Defense contractors “that process, store or transmit Controlled Unclassified Information must meet the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement minimum security standards” and certify that they comply with published requirements. An EAC resource along these lines would provide vendors with clarity about how to assess compliance and agreed-upon metrics.

Similarly, DHS has published resources associated with its Cyber Resilience Review program, which “align[s] closely with the Cybersecurity Framework . . . developed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology.” They include a self-assessment package and a “Question Set with Guidance,” which could prove useful in developing analogous resources for the EAC.

Background Checks And Other Security Measures For Personnel

Much of the conversation about election cybersecurity has imagined attackers in distant lands reaching our election infrastructure through the internet. But some of the most effective cyberattacks of recent years have involved insiders. To mitigate these risks, vendors should demonstrate during certification that they have sound personnel policies and practices in place.

At a minimum, vendors should describe how they screen prospective employees for security risks, including background checks, and how they assess employees for suitability on an ongoing basis, including substance-abuse screening. The Election Assistance Commission should also require vendor disclosure of controls governing staff access to sensitive election-related information. Since the bulk of such sensitive information would presumably not constitute classified information, which is subject to its own set of robust controls, the EAC’s scrutiny of vendor personnel risk management will be critical.

Vulnerability to attacks by insiders is a threat separate and apart from a hack over the internet, demanding entirely different controls and defensive measures. Without adequate personnel screening and other safeguards, vendors that provide critical election services could be exposed to malfeasance from within. The FBI’s thorough background checks for Justice Department attorneys and other law enforcement personnel provide a good model for aggressively vetting personnel. In the event election vendors require access to formally classified information, examples abound in the defense, nuclear, and other sectors of how to handle security clearances.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) regulates personnel in ways potentially relevant to election vendors. Its fitness-for-duty program requires that individuals licensed to operate a nuclear reactor meet several performance objectives, including “reasonable assurance” that they

- “are trustworthy and reliable as demonstrated by the avoidance of substance abuse,” and

- “are not under the influence of any substance, legal or illegal, or mentally or physically impaired from any cause, which in any way adversely affects their ability to safely and competently perform their duties.”

These programs also include “reasonable measures for the early detection of individuals who are not fit to perform the duties.” The regulations include training requirements and penalties for violations, as well as robust substance-abuse testing protocols. The NRC also regulates access to national security information and nuclear-related restricted data by individuals working for entities regulated by the commission.

The defense sector also tightly circumscribes processes on personnel clearances and the handling of sensitive classified information. For example, the National Industrial Security Program Operating Manual (Department of Defense guidance on the regulation of contractors in the industrial security sector) addresses contractors’ protection of such information and the processes for contractor personnel to obtain clearances.

Failure to have robust and adequate personnel safeguards can lead to significant harm inflicted by those on the inside. The Swiss financial institution UBS provides a telling example. A systems administrator who worked for UBS in New Jersey, Robert Duronio, wreaked havoc on company systems after reportedly expressing dissatisfaction with his salary and bonuses. Duronio planted a “logic bomb” in UBS’s systems that activated after his departure and brought down roughly 2,000 UBS computers. The attack cost the company more than $3 million in repairs, in addition to lost revenue stemming from crippled trading capability. (Duronio was sentenced to 97 months in prison.)

We should assume that determined foreign adversaries are capable of hiring programmers who can damage American elections. We have certainly seen foreign governments engage in similar actions against private companies. In 2006, Dongfan “Greg” Chung, a former engineer at Boeing, was arrested for hoarding trade secrets about the U.S. space shuttle program with the intent to pass this information to the Chinese government. Federal agents found sensitive documents in his home, along with journals detailing his communications with Chinese officials. Chung was convicted in 2009 of economic espionage and acting as an agent of China, and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Transparent Ownership

Lack of transparency into ownership and control of election vendors can mask foreign influence over an election vendor and corruption in local certification and contracting. We recommend mandated disclosure of significant — more than 5 percent — ownership interests and a prohibition on significant foreign ownership or control (with the option to request a waiver, if certain conditions are met). The purpose is not only to deter malfeasance and corruption but also to reassure voters that the motives of election vendors are aligned with the public’s interest in free and fair elections.

The threats posed by foreign influence over a U.S. election vendor — including the heightened potential for foreign infiltration of the vendor’s supply chain or knowledge of client election officials’ capabilities and systems — should be obvious. A federal framework for securing elections should limit significant foreign ownership of election system vendors.

Over the last several years, the topic of foreign ownership of election vendors has occasionally made headlines. In 2018, the FBI informed Maryland officials that a vendor servicing the state, ByteGrid LLC, had been under the control of a Russian oligarch with close ties to President Vladimir Putin. In 2019, ByteGrid sold all of its facilities and customer agreements to a company called Lincoln Rackhouse.

At the same time, lack of insight into election vendor ownership presents a serious risk that vendor-led influence campaigns and public officials’ conflicts of interest will escape public scrutiny. Officials might award vendor contracts in exchange for gifts or special treatment rather than to those that would best facilitate free and fair elections. Transparency into ownership and control is required for the public to assess whether officials engaged in procurement and regulation have been improperly influenced.

There are a range of approaches to these problems of improper foreign and domestic influence. We recommend a stringent yet flexible standard: a requirement to disclose all entities or persons with a greater than 5 percent ownership or control interest, along with a ban on foreign ownership in that same amount, with an option for the EAC to grant a waiver after consultation with DHS. While this proposal would address instances of foreign control over election vendors, such as ByteGrid, it could also impact companies such as Dominion Voting Systems, the second-largest voting machine vendor in the United States, whose voting machines are used by more than one-third of American voters and whose headquarters are in Toronto. Similarly, Scytl Secure Electronic Voting, which offers election night reporting and other election technologies to hundreds of election jurisdictions around the United States, is based in Barcelona. A waiver would provide a means for these and other vendors with foreign ties to disclose those relationships and put in place safeguards to prevent foreign influence and alleviate security concerns, thus offering a reasonable path for a wide range of vendors to participate in the election technology market. Beyond this initial disclosure requirement, vendors should have an ongoing obligation to notify their customers and the EAC of any subsequent changes in their ownership or control.

The EAC can look to other sectors for examples of vendor disclosure of ownership or control agreements. The Department of Defense’s National Industrial Security Program Operating Manual is instructive. It requires companies to “complete a Certificate Pertaining to Foreign Interests when . . . significant changes occur to information previously submitted,” and it requires vendors to submit reports when there is “any material change concerning the information previously reported by the contractor concerning foreign ownership control or influence.”

Lawmakers have already introduced legislation to improve transparency in ownership or control of election system vendors, with mechanisms ranging from disclosure requirements to strict bans on foreign ownership or control. One approach recently adopted in North Carolina requires disclosure of all owners with a stake of 5 percent or more in a vendor’s company, subsidiary, or parent, so that the state’s Board of Elections can consider this information before certifying a voting system.

On the other end of the spectrum, the For the People Act and the SAFE Act would require that vendors in states receiving federal grants be owned and controlled by U.S. citizens or permanent residents, with no option for a waiver. Similarly, the Election Vendor Security Act would have required each vendor to certify that “it is owned and controlled by a citizen, national, or permanent resident of the United States, and that none of its activities are directed, supervised, controlled, subsidized, or financed, and none of its policies are determined by, any foreign principal” or agent.

Other proposals would prohibit foreign control but provide for a waiver, as we suggest. For instance, the Protect Election Systems from Foreign Control Act would require vendors to be “solely owned and controlled by a citizen or citizens of the United States” absent a waiver. Such waivers could be granted if the vendor “has implemented a foreign ownership, control, or influence mitigation plan that has been approved by the [DHS] Secretary . . . ensur[ing] that the parent company cannot control, influence, or direct the subsidiary in any manner that would compromise or influence, or give the appearance of compromising or influencing, the independence and integrity of an election.”

With respect to defining an ownership or control interest of greater than 5 percent, the EAC could borrow from the approach used by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). The FCC typically defines foreign ownership, including indirect ownership, by multiplying the percentage of shares an owner has in one company by the percentage of shares that company owns in a regulated broadcast or common carrier licensee. For instance, if a foreign person owned 30 percent of company A, and company A owned 25 percent of company B, the foreign person would be deemed to own 7.5 percent of company B. For purposes of voting shares, the FCC treats a majority stake as 100 percent, whereas for equity shares, the actual percentages are used.

Processes For Reporting Cyber Incidents

Both the public and local and state governments are often kept in the dark about security breaches that affect election vendors. This state of affairs can undermine faith in the vote and leave election officials unsure about vendor vulnerabilities. To address these concerns, vendors should face robust incident reporting requirements and a mandate to work with affected election authorities.

Federal oversight should require vendors to agree to report security incidents as a condition of certification. The Election Assistance Commission should require that vendors report to it and to all potentially impacted jurisdictions within days of discovering an incident. The EAC’s existing Quality Monitoring Program requires only that vendors with certified voting equipment “submit reports of any voting system irregularities.” At present, the reporting requirement extends only to vendors of voting systems and does not encompass any other facets of those vendors’ services, equipment, or operations. Election officials have long complained that vendors do not always share reports of problems with their systems. Compounding the problem, a single vendor often serves many jurisdictions.

Some legislation has already sought to mandate more fulsome incident reporting by vendors. The Secure Elections Act, which had bipartisan support before losing momentum in 2018, included a mandatory reporting provision. Under the bill, if a so-called election service provider has “reason to believe that an election cybersecurity incident may have occurred, or that an information security incident related to the role of the provider as an election service provider may have occurred,” then it must “notify the relevant election agencies in the most expedient time possible and without unreasonable delay (in no event longer than 3 calendar days after discovery of the possible incident)” and “cooperate with the election agencies in providing [their own required notifications].”

Absent robust incident reporting, election officials and the public can be left unaware of potential threats that vendors might introduce into elections. As previously discussed, there is still considerable uncertainty concerning the alleged spearphishing attack and hack of a vendor involved in the 2016 elections. Much of what is known stems from the leak of a classified intelligence report obtained by the Intercept, which identified the hacking victim as a Florida-based vendor, coupled with Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report to the attorney general and indictment of 12 Russian intelligence officers. Further complicating the picture of what happened, the Florida-based vendor, VR Systems, responded to an inquiry from Sen. Ron Wyden (D–OR) via letter, claiming that “based on our internal review, a private sector cyber security expert forensic review, and the DHS review, we are confident that there was never an intrusion in our EViD servers or network.” This uncertainty offers little for the vendor’s clients to rely on in assessing the vendor’s ongoing cyber readiness and whether to continue to contract with the vendor in future elections.

With mandated incident reporting, the EAC could provide the necessary assurance to election officials regarding the security of vendors by sharing information with election officials who need it, as well as by requiring appropriate remedial action, up to and including decertification.

Supply Chain Integrity

Federal regulators should require vendors to follow best practices for managing supply chain risks to election security. The new Technical Guidelines and Development Committee should define categories of subcontractors or products that pose serious risks, such as servers and server hosting, software development, transportation of sensitive equipment such as voting machines, and information storage. For instance, Liberty Systems, one of Unisyn Voting Solutions’ regional partners, would likely be covered, given that it “provides election and vital statistics, software, and support throughout counties in the State of Illinois.” The TGDC’s guidelines could then require that vendors have a framework to ensure that high-risk subcontractors and manufacturers also follow best practices on cybersecurity, background checks, and foreign ownership and control, as well as reporting cyber incidents to the vendor.

This approach is being used in other areas of government, where a growing recognition of supply chain risk to national security exists. The Department of Defense has recently stepped up its enforcement of supply chain integrity and security standards, requiring review of prime contractors’ purchasing systems to ensure that Department of Defense contractual requirements pertaining to covered defense information and cyber incident reporting “flow down appropriately to . . . Tier 1 level suppliers” and that prime contractors have procedures in place for assessing suppliers’ compliance with those requirements.

The Department of Defense now requires that contractors handling controlled unclassified information (CUI) “flow down” contractual clauses to subcontractors whose “performance will [also] involve [the department’s] CUI.” The TGDC should develop an analogous category of subcontractors and manufacturers for which the same cybersecurity, background check requirements, and foreign ownership concerns that apply to election vendors would apply, based on the subcontractor’s role and the opportunity for election security risk to be introduced.

Monitoring Vendor Compliance

To make its oversight most effective, the Election Assistance Commission must have the ability to confirm that federally certified vendors continue to meet their obligations. The fact that a vendor was, at some point in time, certified as meeting relevant federal standards is no guarantee that circumstances have not changed. Failure to stay in compliance should lead to appropriate remedial action by the EAC, up to and including decertification.

The EAC’s Quality Monitoring Program for voting systems provides a starting point for how this might work. The EAC offers a mechanism for election officials on the ground to provide information about any voting system anomalies present in certified voting machines. If an election worker submits a credible report of an anomaly, the EAC distributes it to state and local election jurisdictions with similar systems, the manufacturer of the voting system, and the testing lab that certified the voting system. According to the EAC’s certification manual, “the Quality Monitoring Program is not designed to be punitive but to be focused on improving the process.” The program, then, is focused more on compliance than certification or decertification, although decertification can result in cases of persistent noncompliance.

The SAFE Act and the For the People Act call for the testing of voting systems nine months before each federal general election, as well as for the decertification of systems that do not meet current standards.

A critical difference between the ability to monitor voting equipment and the practices of an election system vendor is that thousands of election officials and poll workers, and hundreds of millions of voters, interact with voting equipment on a regular basis. They can report anomalies when they see them. By contrast, most of the work of election system vendors happens out of public view.

For this reason, vendors must be obligated on an ongoing basis to remedy known security flaws or risk losing federal certification. Congress should provide the EAC with a mandate to ensure that vendors contract with independent security firms to conduct regular audits, penetration testing, and physical inspections and site visits, and to provide the results of those assessments to the EAC. One legislative proposal — the Protect Election Systems from Foreign Control Act — sought to do something similar by subjecting vendors to an annual evaluation to assess compliance with cybersecurity best practices. The EAC’s effectiveness in its new oversight role would be diminished absent some power to monitor vendors’ efforts on this front — a power Congress ought to provide.

The EAC could require regular penetration testing by third parties to assess vendors’ cyber readiness in real time. Such testing would give the EAC (and vendors) an opportunity to identify and remediate security flaws, hopefully before adversaries take advantage of them. The EAC should also consider using bug bounty programs, which have become a common tool deployed by private industry and government entities, including the Department of Defense. Under bug bounty programs, friendly so-called white-hat hackers earn compensation for reporting vulnerabilities and risks to program sponsors. The For the People Act calls for such a program, as does the Department of Justice’s Framework for a Vulnerability Disclosure Program for Online Systems.

Certified vendors should be required to submit to extensive inspection of their facilities. To assess compliance with cybersecurity best practices, personnel policies, incident reporting and physical security requirements, and the like, the EAC must be granted wide latitude to demand independent auditors’ access to vendor systems and facilities. This should include unannounced, random inspections of vendors. The element of surprise could serve as a powerful motivator for vendors to stay in compliance with EAC guidance.

The Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA) performs an analogous, if broader, role for military contractors. Serving as the Defense Department’s “information brokers and in-plant representatives for military, Federal, and allied government buying agencies,” DCMA’s duties extend to both “the initial stages of the acquisition cycle and throughout the life of the resulting contracts.” In that latter stage of a contract, DCMA monitors “contractors’ performance and management systems to ensure that cost, product performance, and delivery schedules are in compliance with the terms and conditions of the contracts.” This function includes having personnel in contractor facilities assess performance and compliance. Although our proposal does not envision the EAC performing an ongoing contract compliance role, the EAC’s enhanced oversight role could take some cues from DCMA’s inspection protocols and ability to closely scrutinize vendors.

The NRC similarly holds inspection rights over those subject to its regulations, including companies that handle nuclear material and those holding licenses to operate power plants. The NRC regulation requiring that those regulated “afford to the Commission at all reasonable times opportunity to inspect materials, activities, facilities, premises, and records under the regulations in this chapter” is of particular relevance to potential EAC oversight. The NRC also has an extensive set of regulations concerning physical security at nuclear sites and of nuclear material. Although these requirements are probably more onerous than those needed in the election sector (especially since nuclear material poses unique physical security risks), they could nonetheless prove instructive in crafting physical security requirements for vendors. Such requirements should go hand in hand with the cybersecurity best practices discussed above.

Enforcing Guidelines

It is critical to have a clear protocol for addressing election system vendor violations of federal guidelines. If states require their election offices to use only federally certified vendors, revocation of federal certification could have a potentially devastating impact on the ability of jurisdictions to run elections and ensure that every voter is able to cast a ballot.

Again, the Election Assistance Commission’s process for addressing anomalies in voting equipment through its Quality Monitoring Program is instructive. If it finds that a system is no longer in compliance with the VVSG, the manufacturer is sent a notice of noncompliance. This is not a decertification of the machine but rather a notification to the manufacturer of its noncompliance and its procedural rights before decertification. The manufacturer has the right to present information, access the information that will serve as the basis of the decertification decision, and cure system defects prior to decertification. The right to cure system defects is limited; it must be done before any individual jurisdiction that uses the system next holds a federal election.

If decertification moves forward after attempts to cure or opportunities to submit additional information, the manufacturer may appeal the decision. If the appeal is denied, then the decertified voting system will be treated as any other uncertified system. The EAC will also notify state and local election officials of the decertification. A decertified system may be resubmitted for certification and will be treated as any other system seeking certification.

The EAC’s application of this process to the ES&S voting system Unity 3.2.0.0 provides an example of how this can happen. Certification of this system was granted in 2009. In 2011, the EAC’s Quality Monitoring Program received information about an anomaly in the system and began a formal investigation. A notice of noncompliance was then sent to ES&S in 2012, listing the specific anomalies found in the voting system and informing ES&S that if these anomalies were not remedied, the EAC would be obligated to decertify the voting system. ES&S attempted to cure the defects, as was its right, and produced a new, certified version of the Unity system. The vendor then requested that its old system be withdrawn from the list of EAC certified systems.

Decertification of a vendor would need to be handled thoughtfully, so that local election officials are not left scrambling to contract new election services close to an election. In this sense, close coordination among federal and local officials and relevant vendors to proactively identify and fix issues would be necessary for any scheme to succeed. The EAC would also have to be left with the flexibility to decide what, if any, equipment and services could no longer be used or sold as federally certified. To that end, decertification should incorporate these key elements:

- A voting system decertification should not necessarily result in a vendor decertification and vice versa. For instance, a voting machine vendor might be found to be out of compliance with federal requirements for background checks on employees. If the EAC determines this noncompliance did not impact the security of voting machines already in the field, it could leave the voting system certified but ban the vendor from selling additional machines (or certain employees from servicing existing machines) until the failure is remedied. Alternatively, it could allow the vendor’s voting machines to continue to be used for a limited time, subject to additional security measures, such as extra preelection testing and postelection audits.

- There should be a clear process ahead of a formal decertification, with notification to affected state and local officials and plenty of opportunities for the relevant vendor to address issues before the EAC takes more drastic action. Only the most urgent and grave cybersecurity lapses should truncate this decertification process.

- Any decertification order should include specific guidance to state and local officials on how existing vendor products or services are affected, assistance to those officials with replacing those goods or services (if necessary), and a road map for the vendor to regain certification.