You’re reading The Briefing, Michael Waldman’s weekly newsletter. Receive it in your inbox.

President Trump’s budget bill grinding its way through Congress is loaded with pork and problems, as these bills tend to be. It makes millions of people ineligible for Medicaid — the biggest health care cut, ever. It preserves tax cuts for the rich. It vastly increases funding for the increasingly out-of-control ICE. It would impose heavy financial burdens on plaintiffs seeking to block illegal government actions.

All of these have gotten headlines. But some provisions quietly slipped into the dense language of this 1,000-page bill may have an impact that is deeper and wider than realized.

Here’s one to worry about: Did you know that the bill would deregulate artificial intelligence?

AI is transforming the economy, social life, and political life. Millions of jobs will be altered or eliminated. Medicine and science may be transformed. States are enacting laws governing everything from privacy to deepfakes to safety rules for driverless cars. What to do about this promising but convulsive technology is a great public policy challenge. AI may feel like a magical being with a life of its own, but AI is a choice.

This budget bill, remarkably, would ban states from setting rules for AI for a full decade, with few exceptions. It would prevent enforcement of laws limiting or regulating AI systems, AI models, and “automated decision systems.” It sounds like something ChatGPT might hallucinate, if the prompt were “write a dystopian science fiction novel, combined with a critique of K Street.”

How did that get in there? Google was feeling lucky, apparently, as were Meta and OpenAI. They all pushed for federal policy that would grant sweeping immunity from state regulation. As it turns out, sitting among Trump’s family and cabinet picks at the inaugural has its perks.

Let us quote, gulp, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene: “I am adamantly OPPOSED to this and it is a violation of state rights and I would have voted NO if I had known this was in there. We have no idea what AI will be capable of in the next 10 years and giving it free rein and tying states hands is potentially dangerous. This needs to be stripped out in the Senate.”

The truth is we don’t fully understand the power and potential of AI — or even how it works.

One dire prognostication, AI 2027, sketches a potential timeline for AI development over the next few years. (Vice President JD Vance says he has read it.) It predicts a future of AI employees, AI arms races, and eventual AI takeover. “We predict that the impact of superhuman AI over the next decade will be enormous, exceeding that of the Industrial Revolution,” the authors warn.

Apple, on the other hand, recently debunked the claim that we are within months of artificial “general intelligence.” Complexity leads to “a complete accuracy collapse,” its engineers report.

Dark forecasts may be wrong. But few can doubt that this technology will bring “creative destruction” on an epic scale.

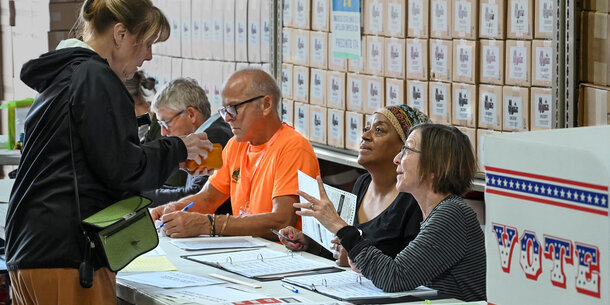

Here’s one policy we at the Brennan Center know a great deal about: voting. AI has the ability to imitate election officials, candidates, and public figures to fuel misinformation and influence elections. And, as more election officials incorporate AI into their work, our election systems risk becoming more biased and error-ridden and less transparent.

In response, Washington veers between timidity and boosterism. President Biden imposed some rules by executive order, but Trump undid them: He appointed David Sacks, an AI investor, to guide policy. Sam Altman of ChatGPT hovers.

When the federal government is silent or paralyzed, it makes good sense for states to step forward — to be the “laboratories of experimentation” described by Justice Louis Brandeis at a time of similar technological change.

In fact, this bill’s override of the states may be illegal. The Supreme Court has said that such “preemption” only occurs when it resolves a conflict between federal and state law. Faced with a technology that could lead to social and economic upheaval, the feds cannot simply refuse to act but also stop states from acting.

Why is this cosmically consequential plan tucked into a budget bill? Because such measures only require 51 votes to pass. They are so big that party members fall in line, forced to vote up or down. In a flawed bid to pass muster under Senate budget rules, Senate Commerce Committee Republicans have suggested that the committee’s version of the moratorium would apply to states that receive funding for broadband access. (It may in fact apply to all states.) Meanwhile, industry lobbyists swarm.

In the early days of the internet, government chose to stand back. Regulation, it was feared, would choke off innovation. Much good came of that, of course. But now we see the harms — a political system flooded by disinformation, massive concentration of wealth, social media that worsens isolation, anger, and depression.

This time we don’t have to wait and see. The risks of legislative inattention, lobbyist prowess, and technological hubris are already in plain sight.