Recent Changes Amplify the Risk of Errors and Privacy Breaches

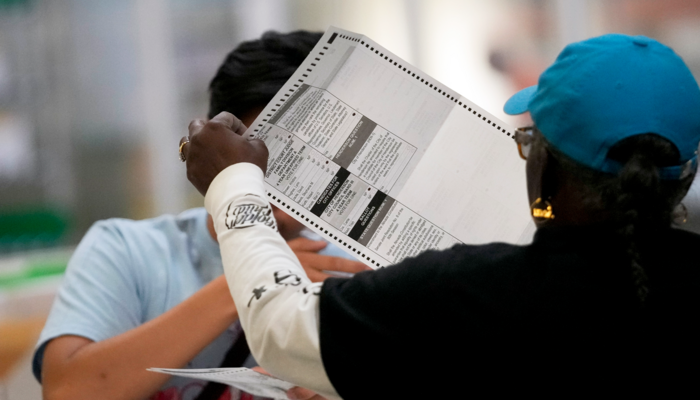

DHS and DOGE recently announced a dramatic overhaul of the SAVE program. Sweeping changes implemented in May allow user agencies to search SAVE using just social security numbers, names, and dates of birth, which expand the search universe beyond people who had gone through the DHS immigration system or had applied for a citizenship certificate. DHS and the Social Security Administration have given the SAVE program access to information about vast numbers of citizens born in the United States in the administration’s central social security number database. And DHS now permits user agencies to query SAVE for information about hundreds of thousands of voters in a single search. Previously, searches could only be conducted for one individual at a time.

USCIS claims that access to social security information will help root out fraud in voter registration, but this claim is misleading. The Social Security Administration’s central social security number database, Numident, does not provide definitive citizenship information in every instance. Only in 1972 did Congress first require the Social Security Administration to establish the citizenship of applicants for social security numbers. The agency only began asking for and maintaining citizenship information for all applicants in 1978. As such, the database does not have comprehensive citizenship information for Americans born before 1978. Naturalized citizens may also not have updated citizenship information in the Social Security Administration database if they did not take action to notify the agency of their naturalization.

These changes follow DOGE intrusions into other federal data systems — those of the Department of Labor and the Internal Revenue Service, among others — that have prompted widespread consternation about DOGE’s access to and handling of Americans’ personal data. They also occur amid revelations that DOGE has fudged or mishandled data to falsely inflate the perceived significance of its activities.

States that collect full social security numbers can conduct bulk SAVE searches with social security numbers in their voter file. But few states currently collect full social security numbers as part of voter registration, rendering this option moot for those states for the time being. Searches in SAVE may also generate a large volume of non-matches because of missing, outdated, or inconsistent citizenship information in the Social Security Administration database and DHS immigration records. In recent guidance, USCIS itself appeared to acknowledge that SAVE’s use of outdated Social Security Administration information may result in non-matches.

Moreover, if a voter cannot be identified using their social security number, the user agency is prompted to resubmit the search using a DHS-issued identification number or direct the voter to the Social Security Administration to update their record. This puts the user agency back in the same position it was in prior to the SAVE program overhaul, or it puts the onus on voters to correct federal records when they are likely already eligible to vote.

Additional Privacy and Oversight Challenges

Beyond its tendency to provide false information, the updated SAVE program raises privacy concerns. Depending on how DHS and DOGE use or disclose data obtained from the Social Security Administration, it may run afoul of federal law, including the Privacy Act and the Administrative Procedure Act. As of publication of this article, the new access to social security data comes without any new or updated system of records notice, required by the Privacy Act to explain to the public how agencies use their data. The Privacy Act also prohibits federal agencies’ unauthorized disclosure of citizens’ and permanent residents’ personal information — a concern in other instances involving DOGE access to similar data. The Administrative Procedure Act, meanwhile, guards against federal agency action that is “contrary to law,” such as a violation of the Privacy Act.

Further exacerbating risks for voters and the election process, oversight of programs like SAVE — and the data that feeds them — is ineffective, with many agencies overseeing themselves. As the Brennan Center has previously explained, internal oversight offices within these agencies can serve to sideline DHS’s main civil rights, civil liberties, and privacy offices instead of fostering accountability in their own programs.

Recent government decisions further undermine oversight. In a unilateral move, the administration largely shut down the USCIS ombudsman and the DHS Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, potentially in violation of statutory obligations. In doing so, it cast aside approximately 600 civil rights investigations, review of intelligence activities, and training for state and local police. This office, alongside privacy and legal advisers, participates in a council that oversees data transfers. With the new changes, the board’s fate remains unknown. So too do the impacts on USCIS, SAVE, and similar programs. But what is clear is that weakened oversight can only hinder steps to ensure data quality, unbiased use, and constraints on inappropriately expansive applications.