When 1965 began, federal voting rights legislation was far from the minds of most in Washington.

After all, Congress had just finished a bruising battle the year before to pass the Civil Rights Act. That bill had been a heavy lift, requiring supporters to overcome a 54-day filibuster by Southern senators that had all but ground other business in the Senate to a halt.

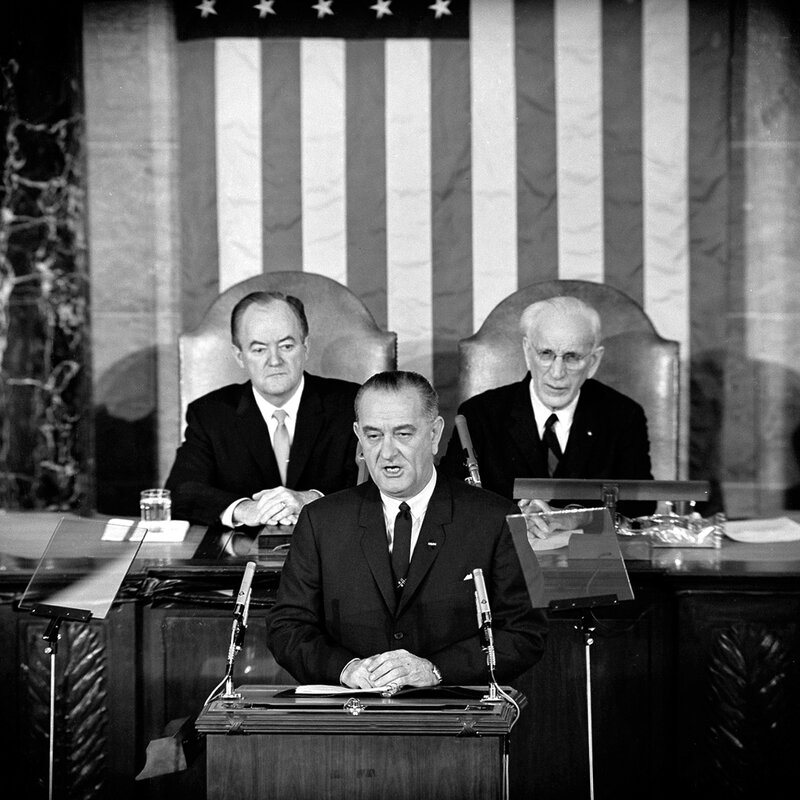

In the new year, it would be enough of a challenge for President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration to oversee the implementation of a law that, among other things, barred discrimination in public accommodations and racial discrimination in schools. Indeed, compliance in the South was already proving predictably uneven and slow going.

President Johnson was also eager to move forward on other priorities on his Great Society agenda, including watershed legislation to create the Medicare and Medicaid system and reform the nation’s outdated and racist immigration laws. Based on lawmakers’ experience passing much more limited voting rights legislation in 1957 and 1960, taking on new voting rights legislation promised an all-consuming fight that could easily derail these and other high priority bills.

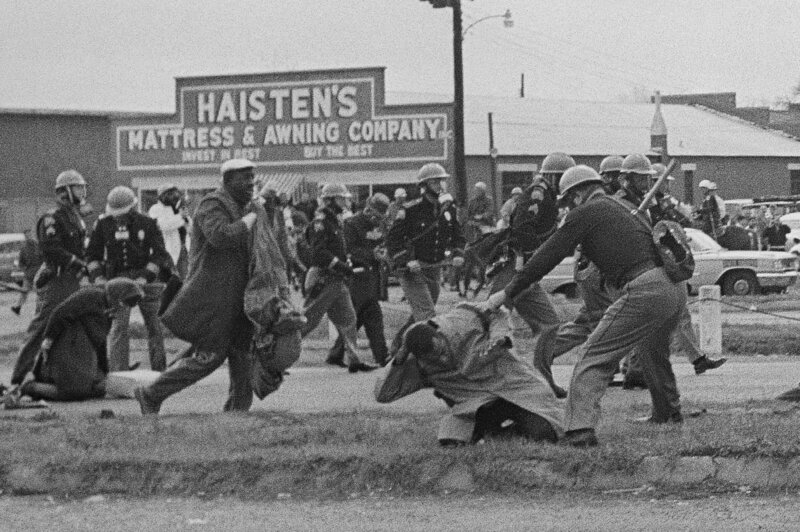

But sometimes history has a way of overtaking plans.

By the end of summer, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 would be signed into law, requiring states to honor the 15th Amendment’s guarantee that the right to vote not be denied because of race.

These are six key moments in the story of how, against all odds, a law that transformed American democracy came to be.