In the spring of 1961, Black and white civil rights activists traveled together on public transportation, setting out on Freedom Rides, to test the segregation laws that defined the Jim Crow South. The interracial bus and train trips were conceived by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) after after two Supreme Court decisions in 1946 and 1960 that found that segregation on interstate buses, and later in facilities for interstate travel, was unconstitutional.

The riders attempted several different trips, such as Washington, DC, to Birmingham, Alabama, and New Orleans to Jackson, Mississippi. They bravely intermingled in the “whites only” sections of buses, trains, restrooms, waiting rooms, and terminals. They were frequently met by violence from angry mobs of white supremacists, prompting federal intervention and drawing national attention to the civil rights movement.

The Freedom Rides influenced other efforts to fight discrimination, and this week marks 60 years since the historic passage of the Voting Rights Act, which banned racial discrimination in voting.

Ahead of the anniversary, we talked with Joan Browning, a white Freedom Rider born and raised in Georgia. She discussed what motivated her to join a Freedom Ride at the age of 19, the significance of voting, and a path forward after the Supreme Court has chipped away at key portions of the Voting Rights Act.

Kendall Verhovek: You joined a Freedom Ride in 1961 between Atlanta and Albany, Georgia. What happened on that ride?

Joan Browning: It was a Sunday afternoon in December. There were nine of us. When we got inside the passenger car, the conductor tried to move us, but none of us would. He finally said, “Well, I guess they’re just deaf.” While we were on that three-hour train ride, I remember us having a picnic, singing songs, and telling stories. The train stopped in Macon, halfway to Albany, for half an hour before we made it.

At the Albany train station, you exit the train at the back side of the station, and then you go into either the white or the colored waiting room. When we reached Albany, we all got off and went into the white waiting room. Our plan was to sit there just long enough to say we sat down before exiting the train station and meeting with people waiting for us to take us home and feed us supper.

When we sat down, the police chief came in and ordered us out. There were an estimated 400 Black people waiting to greet us at the front of the station. When they saw us come out, they started cheering. That upset the police chief, so he ordered to have us arrested. Eight of us were arrested.

Verhovek: You spent the night in a jail cell alone. Can you share that experience?

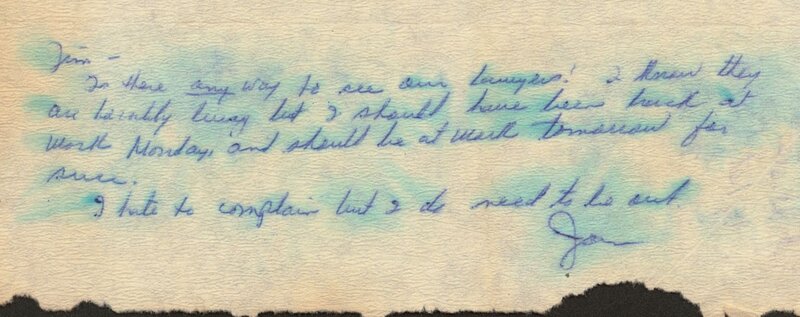

Browning: I was afraid. I was also shocked that when they arrested us, I was separated from the two Black women who were on the Freedom Ride. I thought if you were bad enough to go to jail, you could at least go with your friends. I was in a cell all by myself, as the only white woman who was arrested. But we wrote notes back and forth to each other.

Browning: The wonderful thing about the Freedom Rides is we were so bonded to each other that we looked out for each other. I knew that there were people looking out for me the best they could under the circumstances. We weren’t sure we were going to come back. When the Freedom Rides started, the expectation was, “Don’t sign up for the Freedom Rides if you’re not willing to lose your life over it.” Anything short of not being murdered would be progress.

After we were arrested, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. came down to Albany, gave a speech, and then he led 200 people down to the jail. He was arrested. Later, people would say to me, “Well, did you follow Dr. King to jail?” And I remember being sassy at 19, and I said, “Well, no, he followed us.”

Verhovek: What was the goal of the Freedom Rides?

Browning: The goal was really simple: These were our friends, and we wanted to be able to sit with them on public transportation. We thought this was a simple objective, unlike, say, registering voters. If we could break this one thing, it might help us open doors to voter registration, with supporting candidates for public office, with opening up universities to Black students.

Verhovek: Speaking of voter registration, you have long been an advocate for voting rights. August 6 marks the 60th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act. The effect of the law was immediate: In the first four years after its passage, nearly 1 million Black Americans were registered to vote. And after the 1966 elections, the number of Black elected officials in the South more than doubled, from 72 to 159. Why was it so important to you for the legislation to pass?

Browning: I thought if we could get the Voting Rights Act enforced, it would lead to a total upheaval in who got elected, especially in the South. And it did. It was dramatic, and it was wonderful to see that people finally get to choose their own representatives at different levels of government. In the immediate aftermath, we saw this wonderful change in who sat in these offices, including John Lewis, who first ran for city council several years after the Voting Rights Act passed. But it’s been whittled away at terribly since then.

Verhovek: Yes — over the last decade or so especially, the Voting Rights Act has been severely weakened by the Supreme Court. You lived through this moment where people were beaten and bloodied to just get this legislation, among other civil rights legislation, passed. Now it’s being dismantled. How do you square those two things?

Browning: I think things are now headed back to as repressive as they were before the Voting Rights Act. I can only hope that enough people rise up and say, “We’ve got to make sure that everybody can cast a ballot.” I’ve seen things this bad before, and what it took, and it took some people dying. People actually died. People pay a price for this, but it’s a price well worth paying. I would pay it myself if it were required of me.

I think things are bad enough now, we just got to start over and fix it again.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.