This study has been published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics. The un-paywalled academic version can be found here.

Over the past 18 months, there has been an unprecedented wave of anti-voter legislation introduced and passed across the country. In 2021, at least one bill with a provision restricting access to voting was introduced in the legislature of every state except Vermont. By early May of this year, nearly 400 restrictive bills had been introduced in legislatures nationwide.

Legislators and researchers have given different explanations for this wave. The mostly Republican lawmakers supporting these bills often argue that the new provisions are necessary to protect election integrity, despite the absence of widespread fraud in American elections. Commentators argue that Republican legislators are pushing to change election laws to guarantee political advantages for their party. Some past research supports this argument, demonstrating that certain restrictive voting policies are most likely to be adopted in electorally competitive states controlled by Republicans. Other scholarship shows that states pass restrictive voting laws when Americans of color have strong and growing political power.

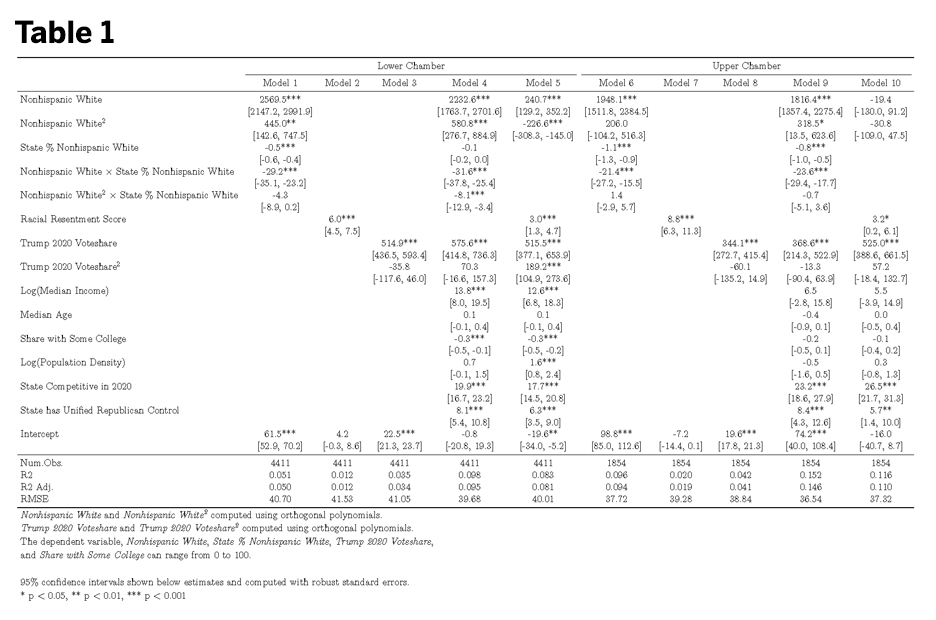

The Brennan Center has developed a unique data set for testing these explanations. Specifically, we tracked every restrictive voting provision introduced in every state legislature in 2021 (as we do every year) and used Legiscan data to identify the sponsors of these bills. We then examine which district-level characteristics are most correlated with whether a lawmaker sponsored a restrictive voting bill.

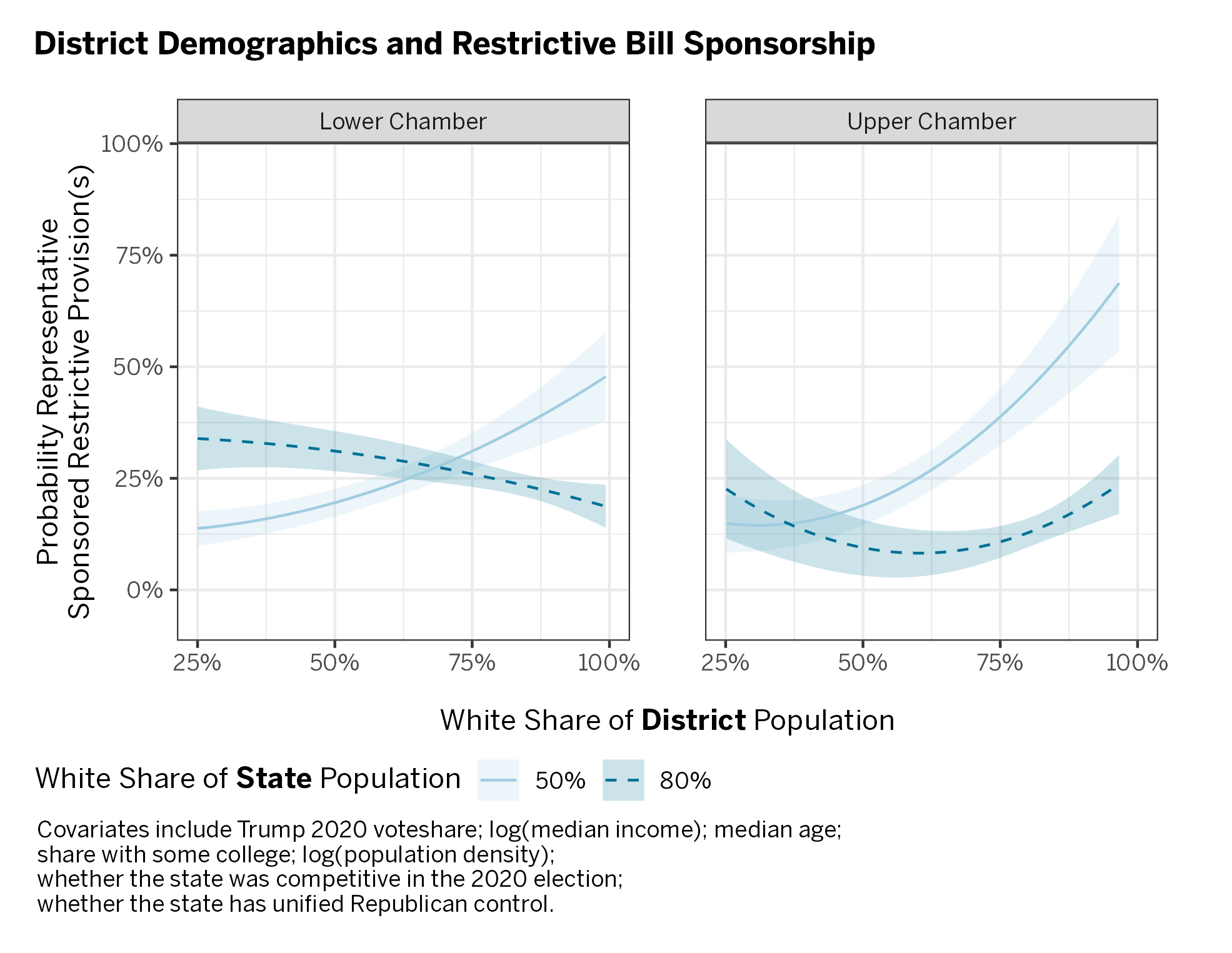

We tested several factors, including the partisan and racial makeup of legislative districts and states as well as the racial opinions of constituents. Our research shows that racial factors were powerful predictors of sponsorship. This is consistent with the theory that “racial backlash” — a theory describing how white Americans respond to a perceived erosion of power and status by undermining the political opportunities of minorities — is driving this surge of restrictive legislation. To be sure, the data also confirm that partisanship is a powerful predictor of sponsorship. But even after accounting for racially polarized voting in the United States, we show that racial demographics are a powerful factor independent of party in determining where restrictive voting laws are introduced and passed.

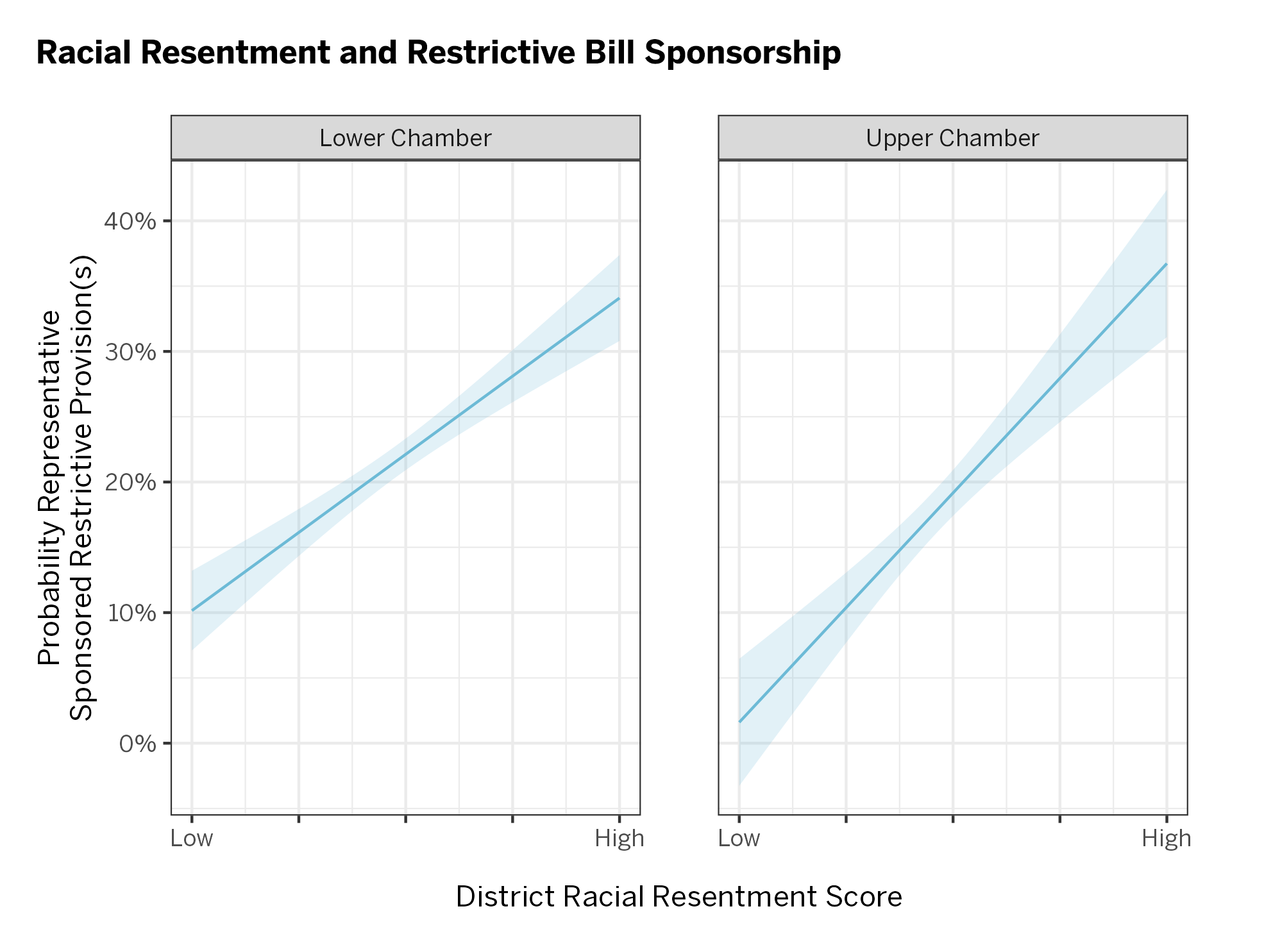

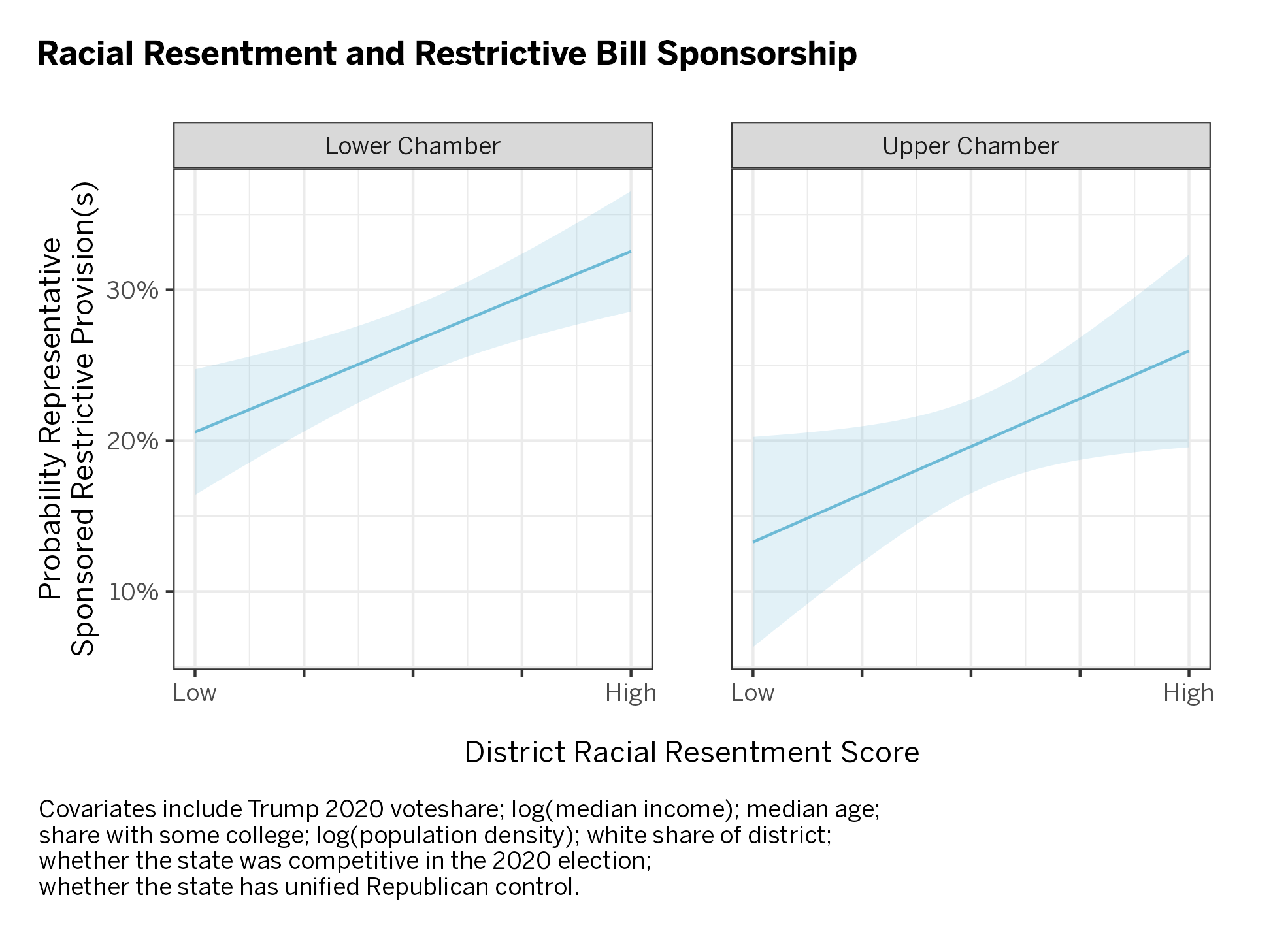

To evaluate the impact that race has on sponsorship, we use two measurements. First, we look simply to the racial makeup of the districts represented by the bill sponsors and their home states. Second, we use responses to a survey called the 2020 Cooperative Election Study (CES). We leverage responses to two questions that have been used for years to measure what political scientists call “racial resentment.”1It’s important to note that this measure does not and cannot identify whether, as the Brennan Center’s Ted Johnson explains, there’s “a racist bone in your body.”

Instead, it measures how white Americans think about the role of race in politics, and it is generally a good proxy — in the aggregate — for how racially conservative Americans are. These scores cannot be used to neatly rank each and every legislative district according to how “racist” it is. Rather, we argue that districts with higher racial resentment scores on the survey are generally more likely to feel threatened by America’s growing racial diversity. The fact that higher scores are associated with higher rates of sponsorship even after accounting for partisanship underscores the explanatory power of these questions.2

Our key findings at the legislative district level include:

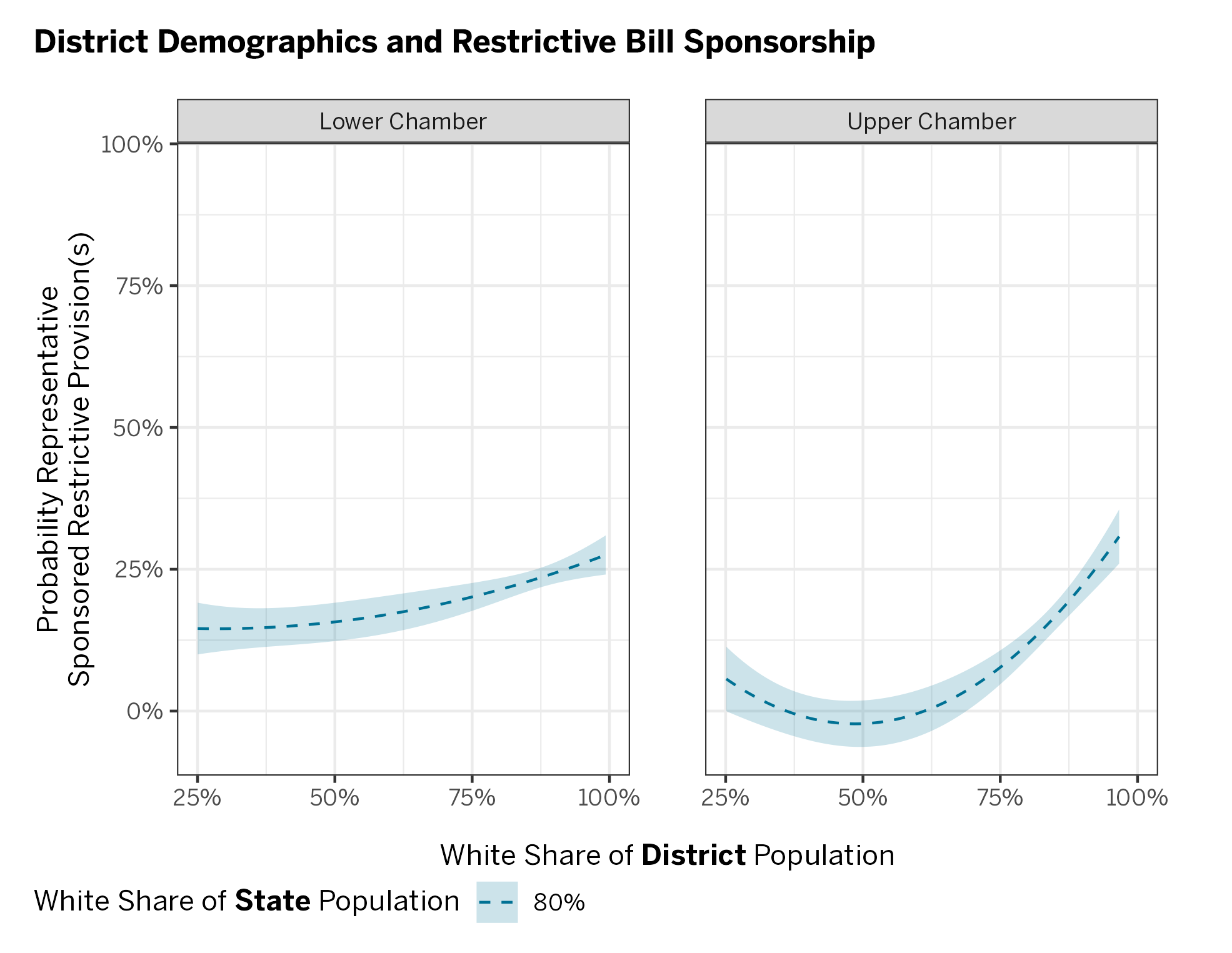

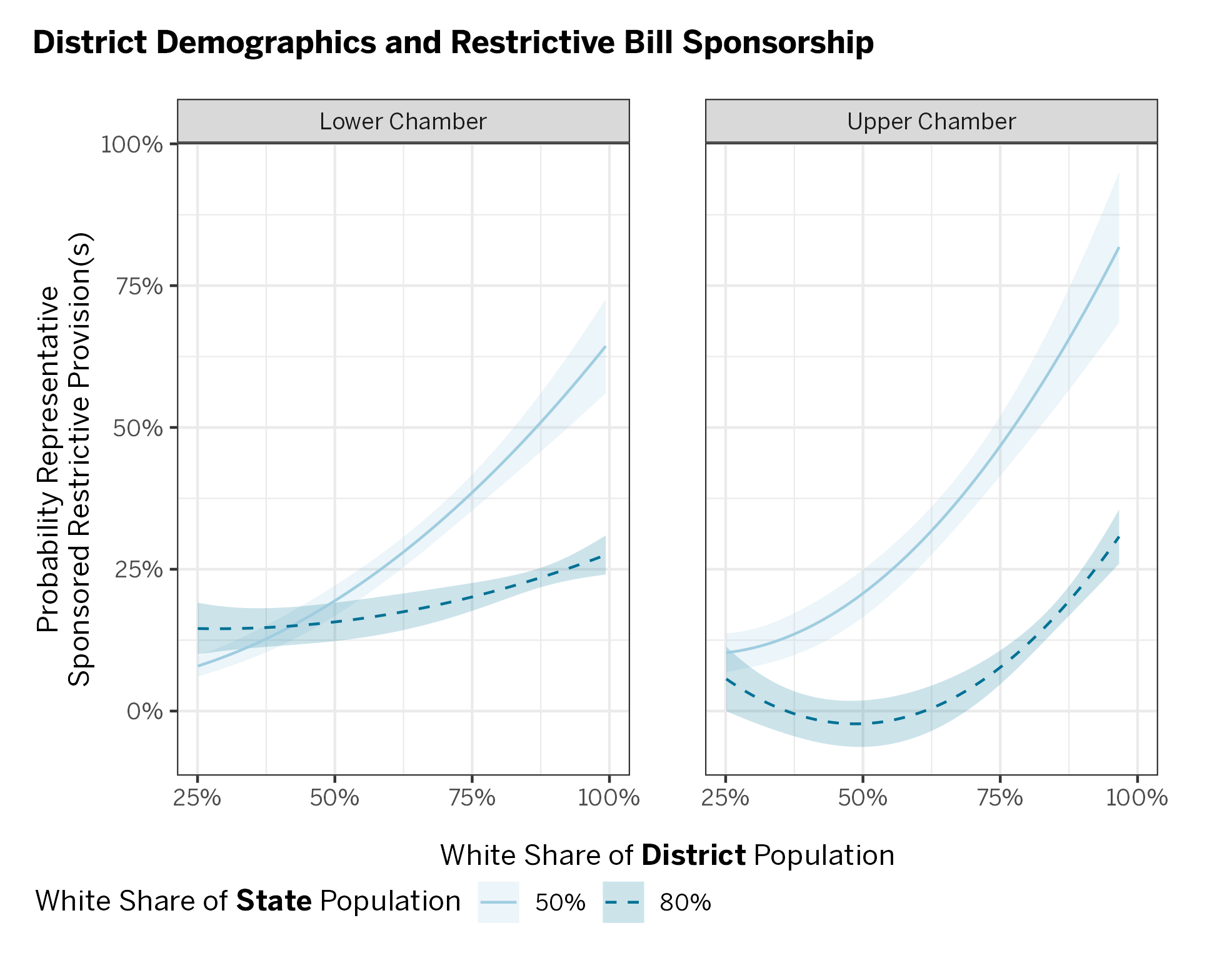

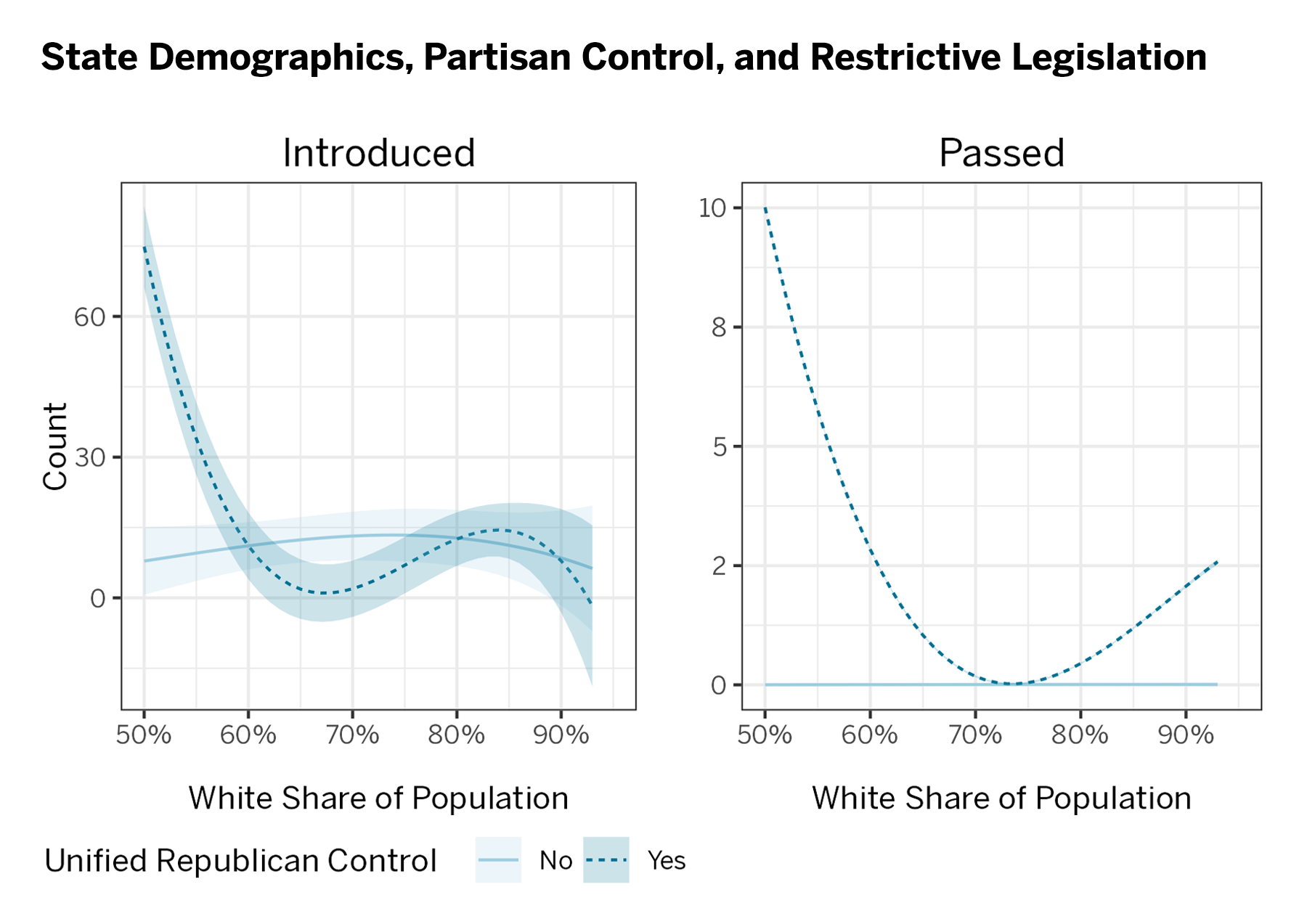

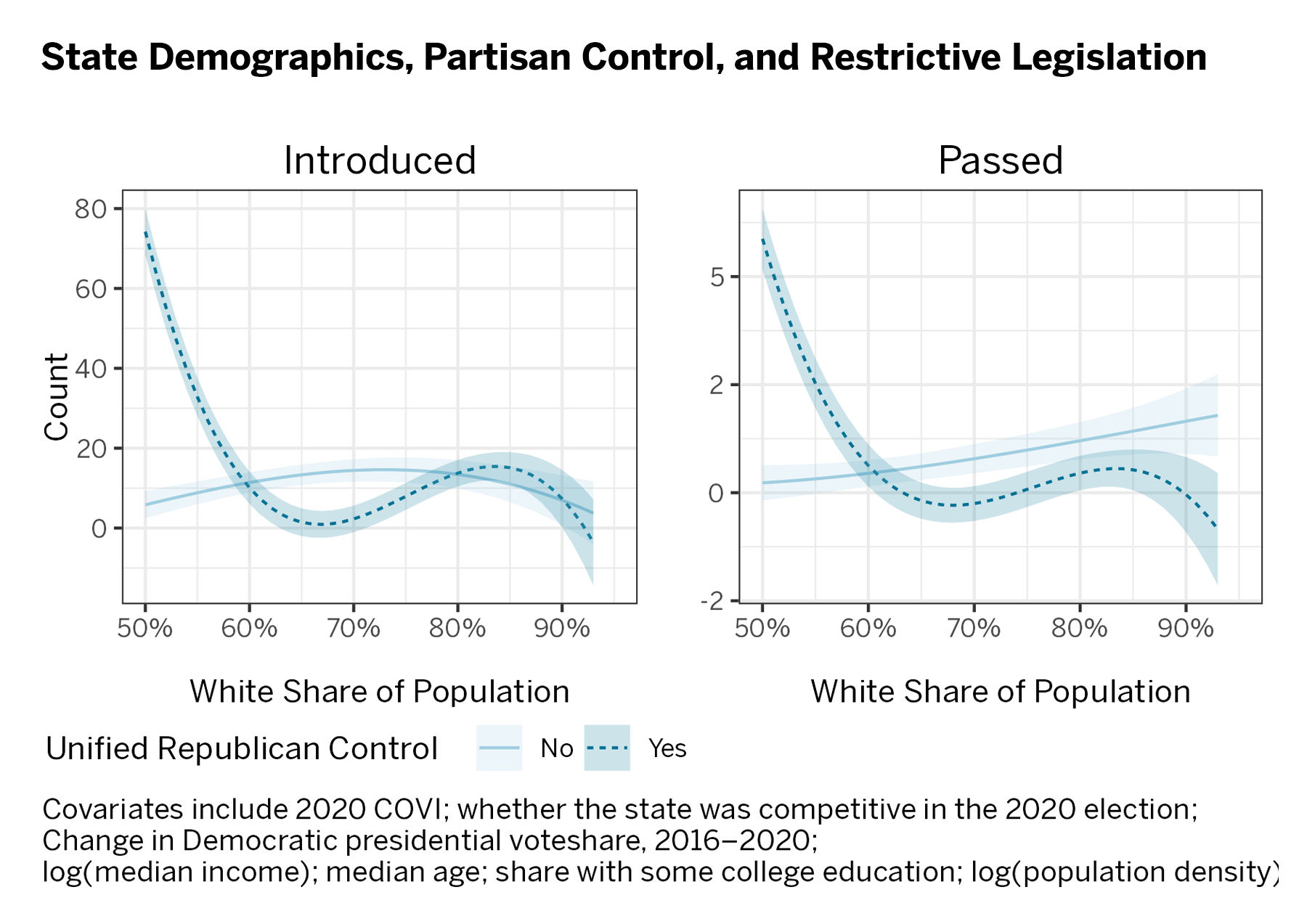

- Representatives from the whitest districts in the most racially diverse states were the most likely to sponsor anti-voter bills.

- Districts with higher racial resentment were more likely to be represented by lawmakers who sponsored restrictive bills.

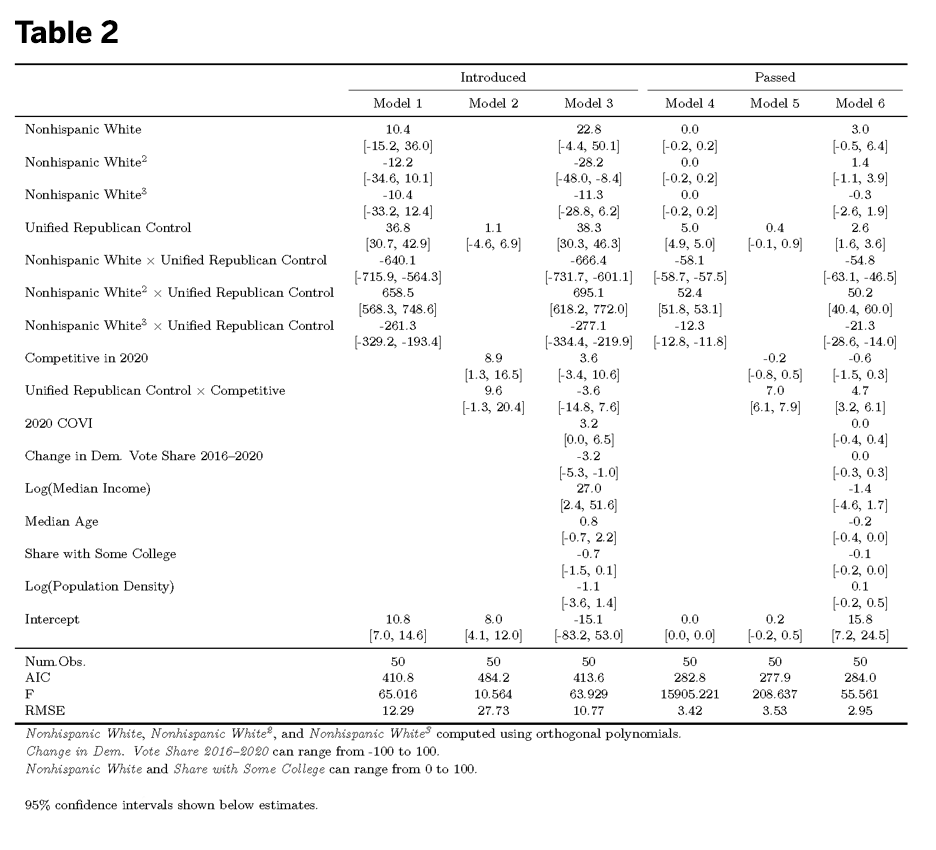

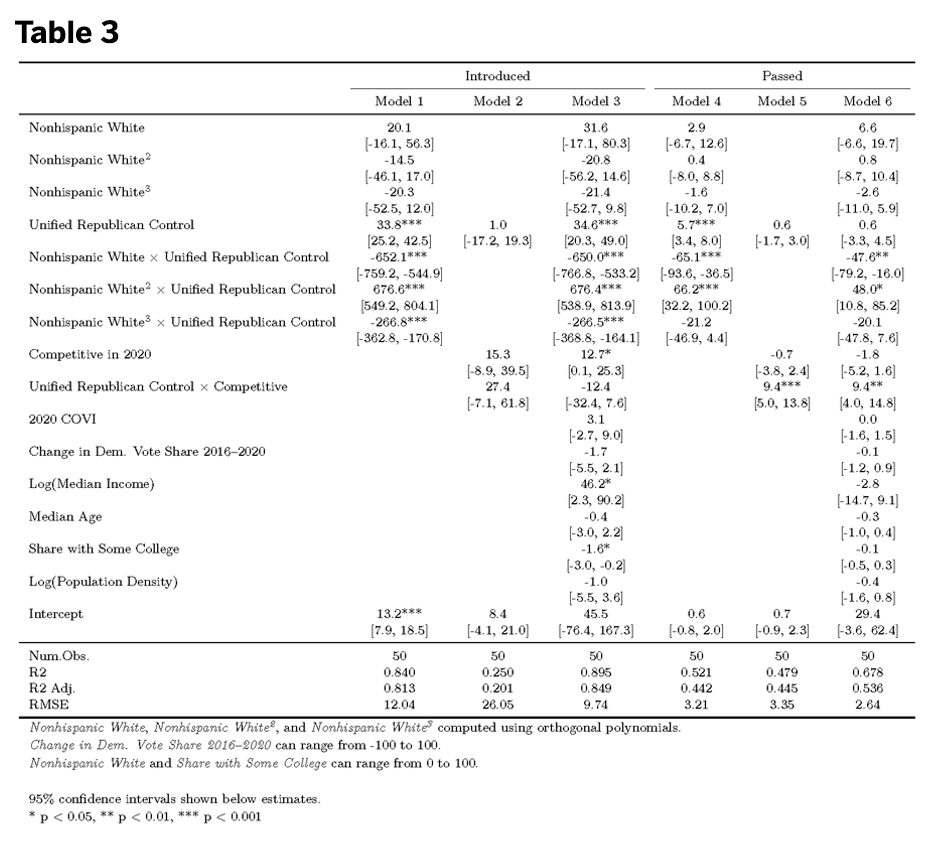

At the state level, we find:

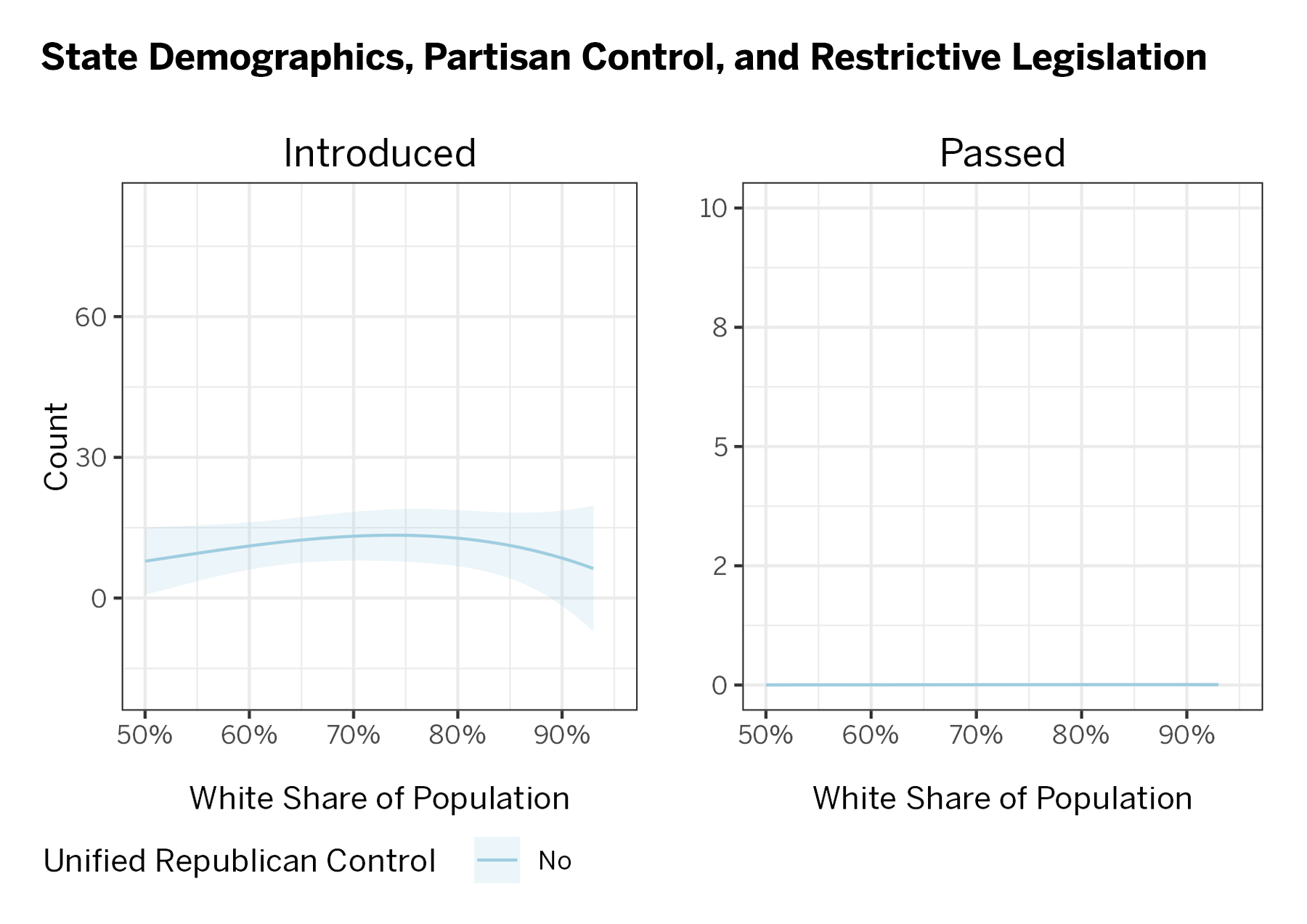

- It is the interaction between race and partisanship that matters. States with unified Republican control are not uniformly likely to introduce or pass restrictive provisions. In fact, predominantly white states are unlikely to introduce or pass restrictive provisions, regardless of which party controls the legislature. But racially diverse states controlled by Republicans are far more likely to introduce and pass restrictive provisions.

Endnotes

-

1

Respondents are asked how much they agree with the following statements on a scale of 1 to 5: “Irish, Italians, Jewish and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without any special favors” and “Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for blacks to work their way out of the lower class.” We reverse code agreement with the second statement. -

2

Some researchers disagree about what precisely these questions capture, given how correlated they can be with other conservative beliefs like individualism, limited government, and self-reliance (see, for instance, this paper). Nevertheless, most political scientists agree that the racial resentment score captures important information about Americans’ racial views, and it remains central to scholarship on race and politics in the United States.