Election denial poses an ongoing threat to U.S. democracy. Despite its widespread rejection in the 2022 midterms, efforts to undermine electoral systems have proliferated and expanded beyond Donald Trump’s charge that the 2020 presidential election was stolen.

This analysis examines the role that election denial played during the midterms and makes an early assessment of how it will continue to evolve ahead of the 2024 election. It does so by outlining 14 tactics deployed by election deniers throughout the 2022 election cycle: (1) election deniers’ bids for office, (2) election deniers’ refusal to concede, (3) counties’ refusal to certify election results, (4) efforts to discredit voting machines, (5) efforts to tamper with sensitive voting data and equipment, (6) massive public records requests, (7) efforts to recruit election deniers to serve as poll watchers and workers, (8) threats against election officials and workers, (9) voter intimidation, (10) mass challenges, (11) election police forces, (12) anti-voter lawsuits, (13) anti-voter legislation, and (14) disinformation.

For each tactic, the analysis walks through what happened during the midterm election cycle as well as new trends that have emerged in 2023. Its findings suggest that a number of these tactics will continue to play a significant role in the next election cycle — including conspiracy-driven attacks on election infrastructure, threats to election officials and workers, election police forces and other government-sponsored initiatives to target voter fraud, increasingly brazen measures to restrict access to voting, and disinformation-fueled efforts to undermine election results. It concludes with an overview of steps that states can take to safeguard our elections in time for 2024.

Tactic 1: Win control of election administration

Pushing false narratives of widespread election fraud, election deniers will continue to run for local and state offices that oversee elections.

Nearly 300 election deniers ran for state and congressional offices in 2022. These candidates, led by notable election deniers, including Kari Lake and Mark Finchem of Arizona, Kristina Karamo of Michigan, and Doug Mastriano of Pennsylvania, promoted a variety of false narratives ranging from allegations of rampant ballot stuffing at drop boxes to claims that electronic voting machines are inherently susceptible to fraud.

Voters repudiated many of these candidates. In six battleground states — Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin — voters uniformly rejected election deniers who ran for statewide offices that oversee elections. In fact, election deniers in secretary of state contests underperformed compared to other non–election denier statewide candidates who lost their races. In states like Nevada, for example, thousands of voters supported the Republican Senate candidate and new governor but rejected the election-denying candidate for secretary of state. According to States United Action, the “election denier penalty” for those candidates amounted to 2.3 to 3.7 percentage points less of the vote than expected. In other words, voters in those states, regardless of party, did not want election deniers running elections. Public polling confirmed that democracy weighed heavily on voters, with 44 percent reporting that concern over the “future of democracy” ranked as their primary concern in the midterms.

Nevertheless, many other election-denying candidates won their races. In Alabama, Indiana, South Dakota, and Wyoming, election deniers now control statewide offices that oversee elections. In battleground states such as Nevada, they secured victories in local election offices in key jurisdictions, including Nye and Storey counties. And at the congressional level, after the midterms, the House now has at least 180 members who questioned or denied the 2020 election results, while the Senate has 17 such individuals.

These victories suggest that election deniers will continue running for office. A January 2023 internal report issued by theRepublican National Committee warns of a “continuing onslaught of Democrat election manipulation,” including “unregulated drop boxes” and “vote collection vans.” The report proposes building a large new organization to counter this fabricated threat, signaling that election-denying candidates will have a more coordinated and sophisticated election denial campaign at their disposal in 2024.

Tactic 2: Refuse to concede electoral defeat

Election deniers will likely continue to protest their losses and file groundless lawsuits in an effort to raise their national profiles.

Most of the election-denying candidates who lost in 2022 conceded defeat. For example, although Wisconsin gubernatorial candidate Tim Michels repeatedly questioned the 2020 presidential election results during his campaign, he admitted defeat in a frank concession speech hours before the Associated Press even called his race. Many others who ran on election denial rhetoric followed suit (albeit reluctantly) in the days after the election.

The following prominent election deniers, however, refused to concede:

- Nevada secretary of state candidate and vocal election denier Jim Marchant did not contest his election’s outcome, but to this day, he has made no official concession statement.

- Michigan secretary of state nominee Kristina Karamo claimed her election was “unlawful” but stopped short of requesting a recount or filing a lawsuit. Of course, Karamo had already filed a pre–Election Day lawsuit that sought to disqualify tens of thousands of absentee ballots cast by Detroit voters.

- In Arizona, attorney general candidate Abe Hamadeh has filed not one, but two suits challenging his defeat after a recount confirmed his loss to Democrat Kris Mayes.

- Arizona secretary of state candidate Mark Finchem filed a suit challenging his loss despite losing by over 120,000 votes. The trial court judge issued sanctions against both Finchem and his lawyer, finding the suit “groundless and not brought in good faith.” Finchem has since called the sanctions “payback” from a “liberal judge” and vowed to appeal.

- Arizona gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake serves as the most visible example. After losing her election by a narrow margin, she pressed on with a highly publicized lawsuit to overturn the results. The Arizona Supreme Court recently rejected six of Lake’s claims, which argued that problems with the ballot printers on Election Day stemmed from intentional misconduct. The court remanded Lake’s last remaining claim to the trial court, where she will face the heavy burden of proving that Maricopa County’s signature-matching process for early mail-in ballots not only violated state law but also altered the outcome of the election in a substantive way.

While Finchem’s court losses will provide some deterrent effect, Karamo and Lake appear to have benefited from their refusal to concede. Karamo, once relatively unknown, became the chair of the Michigan Republican Party in 2023. Lake has floated running for Senate. Hamadeh’s lawsuits have also kept him in the news, as have reports that Jennifer Wright, the former head of Arizona’s Election Integrity Unit, joined his legal team. As these former candidates continue to deny the results and drive election denial discourse as prominent GOP figures, refusals to concede will remain a threat to watch for in 2024.

Tactic 3: Refuse to certify results

With election deniers on the ballot and newly in charge of local election offices, more local officials may refuse to certify elections in 2024.

Local election officials have a nondiscretionary duty to certify elections. But even though certification should function as a ministerial act, the following counties refused to certify or delayed certification processes in 2022:

- Otero County, New Mexico: In the months leading up to New Mexico’s June 7 primary, former professor and attorney David Clements traveled across the state to persuade local leaders not to certify election results. Otero County’s canvassing board followed Clements’s advice and voted to not certify its primary results, citing unsupported concerns about Dominion voting machines. The board eventually relented and certified the results in a 2–1 vote, but only after the New Mexico Supreme Court ordered the canvassing board to fulfill its “nondiscretionary duties.”

- Esmeralda County, Nevada: Just days after the vote to not certify in Otero County, local officials in Esmeralda County, Nevada, voted to delay certifying its primary results in response to one resident’s unspecified complaints of voter fraud; they chose to delay so county officials could recount the county’s 317 ballots by hand. Officials eventually certified the results just hours before the state’s certification deadline on June 24, but not before they and several aides spent more than seven hours conducting a hand recount.

- Berks, Fayette, and Lancaster counties, Pennsylvania: Berks, Fayette, and Lancaster counties refused to properly certify election results by excluding certain ballots from their totals following the state’s May 17 primary. The three counties rejected mail-in ballots that were received before the state’s 8 p.m. deadline on Election Day but were missing a date on the outside envelope. In an opinion issued several months after the primary, a state court ordered the counties to include those “undated mail-in ballots” in their certifications of the returns. They complied within several days of the court’s order.

- Luzerne County, Pennsylvania: During the general election, the board of elections in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, deadlocked over whether to certify its election results. The dispute centered on Republican board members’ claims that paper shortages on Election Day resulted in widespread voter disenfranchisement. A candidate filed suit shortly after the board missed the certification deadline, but the lawsuit was short-lived. The board ultimately certified the results after county officials contacted 125 election officials from the county’s 187 precincts, none of whom reported any voters turned away due to paper shortages.

- Cochise County, Arizona: Most notably, the board of supervisors in Cochise County, Arizona, voted against certifying the county’s returns, citing concerns about whether voting machines had been properly certified. In an interview with the New York Times, one of the supervisors later conceded that their refusal to certify served purely as a protest against the election in nearby Maricopa County, where several Republican candidates made false claims that ballot-printing errors resulted in widespread voter disenfranchisement. The dispute ended after a state court judge ordered the board to certify the results without delay, explaining that the board had no discretion to refuse to certify under Arizona law. In a 2–1 vote, the board certified the results just 90 minutes after the court order.

- Mohave County, Arizona: Mohave County’s board of supervisors also voted to delay certification as a protest against the election in Maricopa County, acknowledging that it was “purely a political statement.” The board eventually voted to certify the results a week later, although two board members noted that they did so “under duress.”

Efforts to refuse to certify and delay election results picked up steam in 2022 but ultimately failed — in large part due to swift, decisive court intervention. They may also prove politically unpopular; in Cochise County, residents are circulating petitions to recall the dissenting supervisor who refused to certify the election results after the state court’s order. In North Carolina, a watchdog group’s complaint prompted the state board of elections to remove two members of the Surry County Board of Elections who (unsuccessfully) sought to block certification. Nevertheless, few of the local officials who voted against certification have faced consequences. With election deniers newly in charge of local election offices, and a likely slate of election-denying candidates on the ballot in 2024, certification disputes may continue.

Tactic 4: Discredit voting machines

Election deniers continue to claim that voting machines are susceptible to fraud and should be replaced by hand-counts.

Election deniers targeted voting machines throughout the midterms. Rooted in conspiracy theories that Dominion voting machines were rigged to alter the 2020 election results, attacks focused on barring the use of machines to record and count votes and shifting to hand-counts of paper ballots.

Vocal conspiracy theorists organized and disseminated the disinformation behind these attacks. MyPillow CEO Mark Lindell claimed that hackers could access voting machines through the internet and tamper with them to steal elections. Nevada secretary of state candidate Jim Marchant similarly argued that “electronic voting machines are so vulnerable and so uncertifiable, I don’t see how we can trust them.” Funding from groups tied to Lindell and former Overstock chief executive Patrick Byrne boosted the movement to eliminate machines, as did Marchant’s organizing efforts; he established a coalition of like-minded secretary of state candidates dedicated to, among other things, banning voting machines in favor of exclusively hand-counting paper ballots.

The hand-count movement in particular gained traction throughout 2022. While useful in limited instances, such as postelection audits, requiring the hand-counting of all ballots creates opportunities for significant delays and errors. Historically, only a handful of localities — mostly small jurisdictions in New England and Wisconsin — have counted ballots by hand rather than with electronic tabulators. But in 2022, at least six states considered legislation to require hand-counts. Localities, including a dozen New Hampshire towns and Washoe County, Nevada, floated similar proposals. Before the April primary, Arizona candidates Mark Finchem and Kari Lake filed a joint lawsuit arguing that Arizona’s voting machines were inherently inaccurate and insecure such that all ballots in the state must be counted by hand (the suit failed, and the court recently issued sanctions against the candidates’ attorneys).

Ultimately, the hand-count movement culminated in two notable showdowns. First, Cochise County, Arizona, made an unsuccessful attempt to conduct a hand-count of all the county’s returns before the general election. In rejecting the county’s plan, an Arizona judge made clear that the county had violated both Arizona law and the state’s election rules, which require counties to conduct manual audits in small, incremental batches. Cochise County later launched a second attempt to conduct a hand-count but withdrew the complaint after the election.

Second, after Marchant personally lobbied officials in Nye County, Nevada, to adopt a hand-count, County Clerk Mark Kampf took up Marchant’s call and insisted on conducting a hand-count of all the county’s ballots in the general election. Although the Nevada Supreme Court ultimately allowed the count to go forward, it did so in part based on Kampf’s decision to scale back his plan to a “parallel” hand-count that would serve as a “test” and not impact the official returns. Notably, Kampf himself conceded at the time that the hand-count had a “very, very high” error rate.

As of the publication of this resource, none of the statewide hand-count bills have passed. And in the most prominent pushes for hand-counts in 2022, one court disallowed the practice under Arizona law, while the other effort saw its main proponent concede that the practice was inherently flawed. The $787.5 million settlement in Dominion’s defamation lawsuit against Fox News may also make attacks on voter machines a less viable strategy.

But after ballot-printing machines in Maricopa County, Arizona, experienced technical problems on Election Day, former President Trump, Lake, and others quickly capitalized on the situation to spread allegations of widespread election fraud. Already in 2023, four states have introduced at least five bills that would ban the use of voting machines to conduct initial ballot counts in any election.

Beyond state legislation, election deniers continue to advocate for hand-counts at the county level. As recently as January 2023, a pressure campaign centered on voting machine conspiracy theories forced officials in Lycoming County, Pennsylvania, to conduct a hand-count of 60,000 ballots from Election Day 2020. Shasta County, California, recently ended its contract with Dominion after similar pressure, buoyed by Lindell’s public support and promises of financial and legal aid. As prominent election deniers like Lindell continue to argue that machines are susceptible to fraud, it appears that hand-counts and related efforts to eliminate voting machines will remain a threat worth watching ahead of 2024.

Tactic 5: Tamper with sensitive voting data and equipment

Election deniers may continue their attempts to gain illegal access to voting equipment and data.

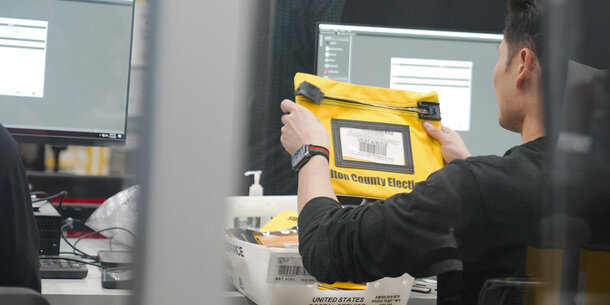

Throughout 2022, officials continued to uncover incidents across the country in which election deniers tried to illegally access equipment and data in an effort to “investigate” the 2020 presidential election results.

Some of these cases involved “insider threats” — incidents in which election officials with connections to conspiracy theorists gave access to or otherwise enabled such tampering. Mesa County Clerk and Recorder Tina Peters, for example, will go to trial on criminal charges related to her alleged role in facilitating a security breach of the county’s Dominion voting machines. The Georgia Bureau of Investigation continues to investigate Coffee County, where a forensic firm hired by Trump lawyer Sidney Powell worked with county officials to copy voting software and data. The same firm attempted to infiltrate election systems in other battleground states, including Michigan and Nevada. Ongoing investigations into these schemes suggest that they are interconnected; many of the people leading them have ties to and received funding from prominent election deniers like Mike Lindell and Patrick Byrne.

Ahead of the 2022 elections, states like Michigan and Colorado worked diligently to decommission any equipment that may have been corrupted. Many election officials also stepped up their preparedness and security measures to prevent and catch tampering. Although reports of potential breaches persisted in the midterms, states did not see the same level of widespread collusion between election officials and conspiracy theorists as in 2020.

As the multiyear investigations into the Michigan and Coffee County breaches demonstrate, collusive efforts between election officials and conspiracy theorists are difficult to track and unravel. For this reason, insider threats remain a seemingly rare but alarming threat ahead of 2024. Election officials and experts continue to advocate for greater protections and resources to safeguard election infrastructure, including but not limited to detailed standards to regulate who can access election infrastructure, funding for security measures like keycard access to facilities that hold voting systems, and state-mandated training for all election officials.

Tactic 6: Massive public records requests

Election deniers may repeat their attempt to overburden local election offices with an abusive volume of records requests and other forms of public access.

Records requests related to the 2020 election soared during the midterms. Election officials generally attribute the surge to prominent election deniers such as Mike Lindell, who urged people to request records at his “Moment of Truth Summit” in August 2022. Following the summit, election offices in nearly two dozen states and counties received overwhelming numbers of identical public records requests.

In North Carolina, for example, hundreds of requests arrived at state and local offices in a single day, while in Massachusetts, requesters used templates distributed by Terpsichore Maras-Lindeman, a podcaster who promotes election-related conspiracy theories. The clerk and recorder in El Paso County, Colorado, received as many as 20 requests a week before the election, up from about one a month before the 2020 election. Officials reported that they were “shrill” in tone and full of conspiracy theories about the 2020 election. Many sought nonexistent documents.

When used properly, state laws that allow access to public records requests can play an important role in increasing government transparency and holding officials accountable. But the 2020 requests effectively weaponized those laws to burden and intimidate officials rather than seek information. State law often requires officials to respond to each request, and even those requests that do not require a response still receive careful consideration and review. The sheer number of these demands forced election offices to divert valuable, already limited resources that would otherwise have been devoted to the midterm elections while also imposing significant financial burdens.

Although attempts to flood election offices with records requests undoubtedly strained administrative resources, officials largely managed to avoid administrative crises. While it remains to be seen whether these tactics will continue into 2024, election officials continue to advocate for greater election administration resources and staff on the assumption that they will.

Tactic 7: Recruit election deniers to serve as poll workers and watchers

Efforts to install potentially disruptive individuals as poll workers and watchers will likely continue in 2024.

Throughout 2022, Cleta Mitchell led the Conservative Partnership Institute’s so-called “Election Integrity Network” — a coalition of conservative leaders, organizations, public officials, and citizen volunteers aimed at gaining control over election administration in battleground states. A critical part of this effort included recruiting and training election deniers as poll watchers and workers. In summits held across the country, network speakers outlined combative strategies for people in these positions to challenge voters and question routine election processes.

During the primaries, these strategies garnered significant media attention and appeared to filter down to the local level. Republican Party officials instructed aspiring poll workers and poll watchers in Michigan to call 911 and contact sheriffs for any election-related complaints at polling locations. A gubernatorial candidate encouraged poll workers to unplug election equipment if they saw “something [they] don’t like happening.” One North Carolina elections director who faced disruptive election-denying poll watchers called May’s primary “one of the worst elections I’ve ever worked.” But come November, the threat failed to materialize. Aside from a few rogue instances of misconduct, the general election saw no significant disruptions from poll workers or watchers at the polls.

Several factors may explain why the threat of rogue poll watchers and workers never came to fruition. First, local election officials have credited coordination between election officials and law enforcement as an effective method of preventing and defusing any disruptions on Election Day. Others have highlighted state and local efforts to educate the public on how ballot-counting procedures work, including on social media and in public information sessions. On an optimistic note, some officials observed that once election skeptics volunteered as poll workers and watchers, received training, and saw the system in action, their viewpoints changed.

While preventative measures may have worked in 2022, the Republican National Committee’s internal report — which purportedly recommends intensive new training models for poll workers and watchers — suggests that 2022’s efforts may have served as a dry run for a broader 2024 strategy. In an April presentation to GOP donors, Mitchell continued to emphasize the importance of “watch[ing]” officials throughout the next election cycle (along with voter suppression tactics, such as limiting voting on college campuses and voting by mail). In the more emotionally charged context of a presidential election, abuses may become more common.

A new wave of election deniers holding state party chair positions also may spur renewed recruiting efforts. State parties can play a significant role in nominating poll workers and watchers in many states. Already in 2023, several prominent election deniers who lost their elections in 2022 (including Karamo in Michigan, Mike Brown in Kansas, and Dorothy Moon in Idaho) have run for and won the GOP party chair position in their states.

Tactic 8: Threaten election officials and workers

Election denial rhetoric continues to fuel threats of violence and other forms of retribution against those who administer elections.

The 2022 election cycle saw a heightened climate of violence against election officials and workers. Just before the general election, the FBI warned that unusual levels of violent threats against election officials and workers persisted in seven states, all of which saw efforts to question the presidential election results in 2020. In Colorado, for example, dozens of election deniers observing a primary recount in El Paso County pounded on windows, yelled at election workers, and recorded them with cell phones. And in the weeks following the general election, social media threats forced one top election official in Maricopa County to be moved to an undisclosed location over safety concerns. These attacks — which often involved racist and gendered harassment — ultimately drove dozens of officials in Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin to leave their positions before the midterms.

Threats against election officials and workers also came in the form of politically motivated criminal penalties just for doing their jobs. Since the 2020 election, 26 states have enacted, expanded, or increased the severity of an estimated 120 election-related criminal penalties for people involved in the election process. In 2022, for example, laws passed in Alabama, Kentucky, Missouri, and Oklahoma responded to conspiracy theories about private funding for election administration by imposing criminal or civil penalties if an election official receives or spends private funding for an election-related activity. These penalties heighten an already fraught landscape for election officials, some of whom are still facing criminal investigations for actions they took to address the spread of Covid-19 during the 2020 election.

Threats against election officials and workers have continued into 2023. Already this year, New Mexico authorities arrested and charged a defeated Republican candidate who allegedly paid others to shoot at the homes of four public servants, including two local election officials. In Arizona, Cochise County’s longtime elections director, Lisa Marra, resigned, citing the emotionally and physically threatening work environment and the public disparagement she faced as she spoke out against the hand-count movement and calls to refuse to certify in Cochise County. The county has since replaced Marra with Bob Bartelsmeyer, who has repeatedly posted false claims of widespread election fraud. As Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold warned, the “extreme rhetoric is not stopping.”

These attacks have consequences. A Brennan Center survey of local election officials found that 45 percent of those surveyed feared for the safety of their colleagues. This fear has contributed to an exodus among election officials; the survey responses suggest that by the time the 2024 elections take place, we will have lost approximately 1.5 election officials per day since the November 2020 election.

Tactic 9: Intimidate voters

In a climate of election denial discourse, conspiracy theories, and reduced firearms regulations, voter intimidation remains a significant threat.

Election officials reported a modest but noticeable increase in voter intimidation throughout the 2022 election cycle. For example:

- Leading up to Election Day, pro-Trump canvassers around the country knocked on voters’ doors in an attempt to verify their voter registrations, resulting in faulty information that would later resurface in mass challenges, discussed below.

- Inspired by the film 2000 Mules and its claims of rampant ballot stuffing at drop boxes, multiple groups recruited and trained volunteers to monitor drop boxes ahead of the election. Melody Jennings, leader of Clean Elections USA, galvanized volunteers by lauding the film and warning of “mules” at Maricopa County drop boxes on Steve Bannon’s radio show and on Trump-owned social media platform Truth Social. Armed individuals affiliated with Clean Elections USA subsequently intimidated Maricopa County voters at drop boxes during early voting, compelling a federal judge to issue an emergency order prohibiting their behavior.

- Polling places saw occasional instances of intimidation. Most notably, in Beaumont, Texas, poll workers interrogated Black voters about their addresses, followed them around the polling location, and stood as close as two feet behind them while they cast their ballots.

Several explanations exist as to why voter intimidation and violence did not escalate further. For one, election officials and law enforcement engaged in a coordinated training and de-escalation effort to prevent disruptions on Election Day. These preventative measures took place against the backdrop of the swift Maricopa County ruling as well as the public prosecutions of those who participated in the January 6 insurrection, creating a credible risk that intimidation and violence would result in the full enforcement of the law. Civil society groups similarly organized de-escalation efforts across the country. Trump’s absence on mainstream social media sites like Twitter also may have played a mitigating role.

Facebook and Instagram have since reinstated Trump’s accounts. Escalating election denial rhetoric, dismantled firearm regulations, and ongoing efforts to disempower election officials from addressing misconduct may significantly increase the risk of voter intimidation in 2024.

Tactic 10: File mass voter challenges

Election deniers may continue to file mass challenges in an effort to burden election offices and intimidate voters.

Armed with information pulled from amateur data matching, activists motivated by false claims of widespread voter fraud flooded election offices with mass challenges to disqualify voters or remove them from the rolls across Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Michigan, and Texas. In Georgia, the state legislature invited mass challenges by passing S.B. 202; after the law made clear that individuals could challenge an “unlimited” number of voters in their county, groups and individuals in at least eight counties challenged an estimated 92,000 voter registrations. In Gwinnett County alone, the group VoterGA worked with local residents to challenge at least 37,000 voters (over 6 percent of the county’s active voters). In Michigan, Election Integrity Fund and Force attempted to challenge over 22,000 ballots from voters who had requested absentee ballots for the state’s August primary.

Several election denier–backed groups facilitated and funded the challenges. For example, the Conservative Partnership Institute distributed an instruction manual that walks through how local groups can vet voter rolls. The America Project, launched by prominent election deniers Michael Flynn and Patrick Byrne, funded VoterGA’s efforts in Gwinnett County. Former Sen. Kelly Loeffler similarly funded Greater Georgia — an organization that sponsored a training session on filing challenges in the name of protecting “election integrity.”

Fortunately, local officials largely rejected these challenges. In Georgia, local election officials threw out most of the challenges to voter registrations, though they upheld at least several thousand. In Michigan, the secretary of state’s office rejected the 22,000-ballot challenge from Election Integrity Fund and Force in its entirety. This outcome suggests that challengers may have placed too much faith in local boards aligning with their efforts. Instead, boards appeared to heed warnings that mass challenges violated state and federal law. But this caution may not hold in those jurisdictions where partisan actors can populate local boards with activist election deniers.

Although the challenges did not formally succeed, they nonetheless may have confused or intimidated the many voters who faced challenges to their eligibility such that they refrained from voting altogether. They also placed an immense burden on local election offices, which struggled to review the challenges while also performing their other election duties. For example, VoterGA’s challenges forced Gwinnett County’s election board to divert 5 to 10 of its staffers, six days a week, to sort through the 37,500 challenges.

It remains to be seen whether mass challenges will continue in 2024. The prognosis may depend in part on the landscape in Georgia; there, legislators are considering yet another bill to make it even easier to disqualify voters through mass challenges, while a pending lawsuit against True the Vote argues that the group’s mass challenges in 2022 amounted to voter intimidation and coercion under the Voting Rights Act.

Tactic 11: Create election police forces

States continue to create and deploy election police forces in an effort to deter eligible voters from participating in elections.

Promises to crack down on supposedly widespread voter fraud played a central role in political campaigns and discourse throughout the midterms. Most tellingly, just five days before Florida’s 2022 primary, Gov. Ron DeSantis announced that the state’s new Office of Election Crimes and Security had arrested 20 people with past felony convictions for allegedly voting while ineligible in the 2020 election. Already, several judges have questioned whether those prosecuting the charges have the authority to do so. And jurisdictional problems aside, the arrests rely on weak evidence that has made local prosecutors reluctant to pursue charges.

The timing of the arrests, coupled with Governor DeSantis’s efforts to drum up publicity around them, suggests that the state intended the new unit and these prosecutions to deter eligible people with felony convictions from voting in the midterm elections. Already, a report by the Marshall Project found that the prosecutions in Florida discouraged people with prior convictions from voting across the country. And there is good reason to believe that Florida’s election crime force will disproportionately target and intimidate Black voters: thus far, the vast majority of individuals arrested by the office are Black.

Virginia and Ohio joined Florida in creating similar units to investigate election fraud in 2022, while Georgia expanded the power of its bureau of investigation to pursue election violations. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton added a new General Election Integrity Team to the state’s existing election integrity unit, although a recent Texas Court of Criminal Appeals ruling has called his prosecuting authority into question. While none of these units have secured significant convictions thus far, they have provided powerful political fodder to state officials, who promoted their efforts to root out fraud on the campaign trail.

Election police forces show no signs of slowing down. In Florida, state legislators circumvented reluctant local prosecutors by passing a bill that expands statewide prosecutors’ authority to pursue voter fraud charges. In Texas, legislators recently proposed allowing the secretary of state to appoint “election marshals” to investigate violations of election law. Even as election police forces secure few actual convictions, this momentum suggests that they will continue to serve as a significant campaign and intimidation tool throughout the 2024 election cycle.

Tactic 12: Use the courts to suppress votes

Election saboteurs and election deniers will likely continue to file lawsuits to limit the freedom to vote.

According to Democracy Docket, an estimated 93 lawsuits aimed to make it more difficult for individuals to vote in 2022. Rooted in conspiracy theories that mail voting resulted in widespread voter fraud in the 2020 election, the majority of these cases attacked access to mail voting and drop boxes in battleground states like Arizona, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Compared to 2020, an increasing number of anti-voter suits also attacked election administration processes. The suits argued, for example, that voting machines facilitated widespread fraud and that state laws compelled localities to hire specific numbers of Republican poll workers, despite a national poll worker shortage.

These lawsuits saw mixed success in the midterms. While courts rejected the vast majority of claims plainly rooted in conspiracy theories, some anti-voter suits succeeded. In Delaware, for example, a state court struck down the state’s mail voting statute less than two months before the general election. Further, the timing of these cases exacerbates their danger. Most were filed immediately before Election Day, sowing confusion about how and when people could vote.

Anti-voter lawsuits largely failed to change the outcome of elections in 2022. But without negative consequences for those who seek to use the courts to disenfranchise voters, even a low success rate will provide an ongoing incentive to file anti-voter lawsuits. Unprecedented fundraising for election litigation — major political parties raised $154 million in the 2021–2022 cycle — further signals that election-related lawsuits, including anti-voter disputes, will carry on into 2024.

Tactic 13: Pass anti-voter legislation

Legislators continue to introduce measures aimed at reducing voter participation and interfering with election processes.

In 2022, lawmakers in 39 states considered at least 408 restrictive voting bills. Ultimately, eight states enacted 11 restrictive voting laws, 5 of which were in place for the midterms (MS H.B. 1510, MO H.B. 1878, NH S.B. 418, OK H.B. 3364, SC S.B. 108). The restrictive voting laws passed in 2022 generally made mail voting and voter registration more difficult, especially for voters of color and other demographic groups who participate at lower rates. For example, Ohio H.B. 458 imposes strict photo ID requirements for voting and, among other things, eliminates a day of early voting, prohibits prepaid postage, and shortens the deadline to apply for and return mail ballots. Early studies suggest that these new restrictions have negatively impacted targeted voters and contributed to a growing racial turnout gap.

Lawmakers in at least 27 states also introduced 151 election interference bills — legislation that enables partisan actors to meddle in elections or target those who make elections work. At least seven states passed 12 of these bills, 11 of which were in place for the midterms (AL H.B. 194, AZ H.B. 2237, AZ H.B. 2492, FL S.B. 524, GA H.B. 1368, GA H.B. 1432, GA S.B. 441, KY H.B. 301, MO H.B. 1878, OK H.B. 3046, OK S.B. 523). The election interference laws passed in 2022 include laws imposing new criminal or civil penalties on election officials, redirecting authority to political actors to prosecute election-related crimes, and increasing partisan influence over election administration structures. For example, 2 laws passed in Georgia create a risk of interference in elections and election results by allowing partisan actors to replace current election superintendents and create new county boards of elections in Miller and Montgomery counties.

State legislatures have picked up speed in 2023. Already, lawmakers in 32 states have pre-filed or introduced 150 restrictive voting bills, many of which would limit mail voting or impose new voter identification requirements. Legislators have also pre-filed or introduced 27 election interference bills in 2023, including proposals that would impose new criminal penalties on election officials for doing their jobs and enable political actors to prompt, initiate, or conduct audits of elections. While it remains to be seen whether the rapid pace of introduction will translate into an increase in passed legislation, these bills suggest that lawmakers will continue to follow the same playbook ahead of 2024.

Tactic 14: Spread disinformation

Election deniers continue to spread false claims about elections.

Election deniers deployed four core, or “sticky,” false narratives during the 2022 election cycle: conspiracy theories depicting voting machines as vehicles for widespread voter fraud, false claims that mail voting and drop boxes are insecure, baseless accusations of votes cast by noncitizens or with the names of dead people, and false claims of fraud in vote counting. They often latched on to breaking news events to spread disinformation tied to these four false narratives, such as the printing issue that affected some Maricopa County voting machines on Election Day or the technical glitch that briefly impacted electronic poll books in Detroit.

Communities receptive to these false narratives clustered around notable “spreaders” who fueled viral rumors as they traveled online, such as Mayra Flores in Texas, Mark Finchem in Arizona, and Doug Mastriano in Pennsylvania. And as Election Day drew closer, online discussions of such fraud significantly increased. Although many election officials worked successfully to “pre-bunk” false information during the midterms, disinformation remained a powerful force, particularly in ”news deserts” that lack local newspapers and digital news sites.

Disinformation is here to stay. Recent attacks on the Election Registration Information Center (ERIC) reveal a new iteration of election disinformation that threatens to undermine even widely respected, bipartisan institutions aimed at preventing voter fraud.

Created in 2012, the data-sharing system has served as an important, if little-known, tool for helping states keep voter rolls up to date by identifying voters who may have died or moved out of state. In January 2022, a far-right website with a history of spreading election disinformation published the first of several blog posts about the system, falsely implying that “left-wing activists” created the program as part of a conspiracy to influence elections. Just seven days later, Louisiana became the first state to withdraw from the program. Suddenly, election officials who previously lauded the group as a “godsend” and “one of the best fraud-fighting tools that we have” reversed course.

Alabama announced its exit in late 2022, trailed by recent announcements from Florida, Iowa, Missouri, Ohio, and West Virginia in March 2023. The exodus may continue; Trump has since urged all Republican governors to sever their ties with the group. One of ERIC’s developers has pointed out the underlying irony: “States that leave ERIC will see more dead voters and voters who have moved away on their lists, and reduce their ability to detect double-voting. As a result, they will likely see longer voting lines, more undeliverable mail, and take longer to count ballots.”

• • •

Election denial remains a real and growing threat that could seriously undermine our electoral system if left unchecked. In many ways, the stakes will be higher in 2024 — a presidential election year that will include the same candidate who served as a lightning rod for violence in 2020. This year has already seen more frequent and forward-looking attempts to undermine elections than at this point in the 2022 cycle, when election deniers continued to focus primarily on the 2020 presidential election.

Fortunately, there is still time to prepare for and prevent election denial efforts ahead of 2024. Ideally, Congress should strengthen our democratic guardrails by enacting baseline standards that safeguard voting and the administration of federal elections. In the absence of congressional action, states can and should strengthen their laws to protect against the spread of false information, strengthen their laws to safeguard election administration and voting rights, counter election subversion, and prevent intimidation and violence against election personnel and voters.

A thorough state legislative agenda to promote election security and protect against election subversion should include, among other things, legislation that gives election officials more flexibility to count mail ballots faster (and thereby avoid the mistrust that comes with reporting delays), establishes restrictions to protect election systems from tampering and unauthorized access, and expands physical security and privacy protections for election officials and workers. This agenda should also ensure that adequate legal mechanisms exist to thwart efforts to subvert elections, including measures to clarify that certification is a ministerial and nondiscretionary duty, mechanisms for moving certification forward in the face of obstruction, and provisions empowering state courts to swiftly resolve election disputes. And it should prioritize adequately protecting voting rights and establishing clear standards for guaranteeing a clear and accurate count.

Forthcoming Brennan Center work will outline these and other state-level reforms in greater detail.