Election-related falsehoods corrode American democracy. Since 2020, lies about a stolen presidential election cropped up in dozens of campaigns for election administrator positions and spurred unprecedented threats to election officials. The result has been a deluge of resignations that drained expertise from election offices across the country. Further, public trust in elections has plummeted amid disinformation promoted by Donald Trump and other prominent election deniers.

The health of our democracy depends in part on our success in guarding against damage from election misinformation. That’s why last year, we launched the Midterm Monitor interactive tool to better understand the online conversation about the election. Our research surfaced striking patterns in election misinformation. It also revealed that certain strategies are likely to be more effective in combatting election falsehoods than others.

Starting in September, the Midterm Monitor collected posts and information from Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube accounts affiliated with candidates for the House, Senate, governor, and secretary of state. The monitor also collected posts and information from the accounts of influential national media outlets and pundits, top local media outlets in 10 battleground states, Spanish-language U.S. media outlets, and state media and diplomats associated with the Chinese, Iranian, and Russian governments.

Using the Midterm Monitor, we confirmed that high-profile election deniers rely on the same core false election-related narratives that are repeated time and time again. This pattern shows that internet and social media companies, election officials, journalists, and civic groups can “prebunk” many of the central elements of false stories ahead of Election Day.

Our research also showed that networks of important influencers and online communities helped election falsehoods spread in the midterms, demonstrating the usefulness of network analysis as a tool to track indicators of harm and slow the spread of election lies. And we unearthed key differences in the way election deniers use each social media platform that should be accounted for in crafting a comprehensive strategy to combat election misinformation.

Lesson #1: Election denial relies on core false narratives that recur and evolve.

Between mid-August and the end of November, a team of analysts read through thousands of social media posts captured by the monitor and conducted an automated analysis of tens of thousands of posts. We found that a large share of misinformation reflected themes that were the same or similar to those in the 2020 election. Our research empirically showed a phenomenon that others have observed: prominent election deniers rely on a core set of false narratives around voting machines, mail voting, and voter fraud. This pattern allows for potentially effective prebunking of these central themes.

These core false narratives are “sticky” — they recur, repeat, and evolve. Throughout the four-month tracking period, certain misinformation tropes turned up again and again: conspiracy theories depicting voting machines as vehicles for widespread voter fraud, false claims that mail voting and drop boxes are insecure, baseless accusations of votes cast by noncitizens or with the names of dead people, and false claims of fraud in vote counting.

To recycle these core themes, spreaders of misinformation often latched onto breaking news events to spread falsehoods. In the lead-up to the election, for example, some candidates exploited the news that a Dominion voter assist system for printing ballots ended up for sale on eBay to cast doubt on vote totals from voting machines.

On Election Day, influencers evoked the same deceptive theme in connection with an unfolding news story in Maricopa County, Arizona, where a printing issue affected a number of vote-counting machines for some time. The later-resolved technical glitch — which interrupted operations at about one in four poll sites — ignited a firestorm of false claims about voting machines. Some individuals cast doubt on whether ballots would be properly counted and accused election officials of changing ballots after the ballots were deposited in secure collection boxes. A widely shared video featuring a poll worker promoting the false claims got 4.5 million views in under a day.

Our election system has checks in place to prevent fraud in vote counting and to guarantee that machines count votes accurately. In Maricopa County, officials confirmed that all eligible voters had safe options to cast ballots throughout Election Day. However, the recipe of a familiar false trope combined with a specific, late-breaking event provided fertile ground for misinformation to thrive.

On Election Day, influential election deniers also seized on a quickly resolved technical glitch in Detroit to misrepresent, extrapolate, and connect the isolated issue to a major misinformation narrative. At the polls, some Detroit voters were issued ballot ID numbers that electronic poll books initially showed as matching an absentee ballot. This problem stemmed from a data issue with some poll books that officials quickly addressed, and all eligible voters were able to cast ballots. But Michigan secretary of state candidate Kristina Karamo (R) and other influential accounts capitalized on the issue to baselessly argue that mail voting leads to widespread fraud.

In our preelection tracking, we saw numerous social media posts falsely claiming that drop boxes, voting by mail, or absentee voting are vehicles for mass voter fraud. In fact, mail ballots have been successfully used in the United States for over 150 years, and in that time, states have developed multiple layers of security to protect against malfeasance.

The common arsenal of themes is part of the information infrastructure that election deniers operate in. Instead of having to start from scratch, they often hark back to the same themes and link them to the news of the day. Election deniers do not reinvent the wheel — and efforts to combat misinformation do not have to either.

Recommendation: Companies, officials, and organizations should more effectively “prebunk” core misinformation themes.

Our Midterm Monitor analysis offers lessons for effective and efficient prebunking and debunking of misinformation in future elections. In future elections, election officials, civic groups, news organizations, and social media and internet companies — including Facebook and Google — can get ahead of the curve and help stem the tide of election misinformation. In so doing, they can build on existing efforts to educate the public in timely and strategic ways.

Before elections, officials and organizations should take action to inoculate against common misinformation tropes. Social media sites should pin or host “information boxes” containing content from authoritative sources, including election offices, to explain existing election security safeguards, the reliability of voting and vote-counting machines, the trustworthiness of mail ballots, and the timeline for counting votes and certifying elections. News outlets can publish more stories on voting machines, mail ballots, and election results early and with important context. Civic groups should facilitate digital literacy trainings that prepare constituents to recognize common conspiracy themes.

Across party lines, election officials largely remain highly trusted sources of election information. They too can take proactive steps to rebut core conspiracies and stave off rumors and lies. In the lead-up to elections, these officials can run voter education campaigns and maintain tip lines and rumor-control pages where possible. They can build contact lists and relationships in secretary of state offices, within the media, in community groups, and with candidates of all affiliations to amplify accurate information. Internet companies should offer trainings to election officials on search engine optimization and keyword use to help boost critical information.

In the past election cycle, some election offices provided early, accessible, and transparent information to the public to prebunk core false narratives. Their actions offer a roadmap for officials who seek to preempt viral lies and rumors on or after Election Day and prepare the public to meet common election myths with a skeptical eye.

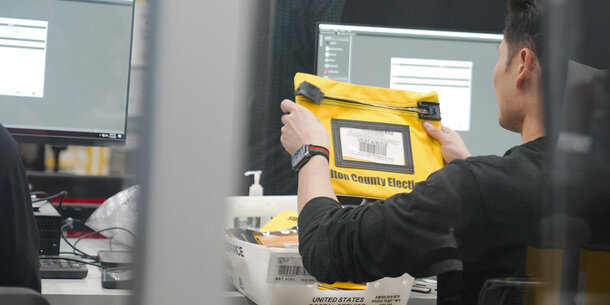

For example, the Ohio secretary of state created a detailed video about how absentee ballots are printed, mailed, and counted. In depicting election workers inside an election office, it reminded the public that election administration is a process conducted by community members in a professional setting, not a secretive sham unfolding behind closed doors.

In some Texas counties, election administrators invited members of the public to tour their offices and participate in accuracy testing for voting machines. And just before the polls closed on Election Day, the Michigan Department of State posted an infographic to Twitter with a timeline for vote counting. The post explained that absentee ballots take longer to process than votes cast in person and that voters could expect unofficial results 24 hours after polls closed.

On Election Day, crisis preparation is also key when innocent glitches occur and core false narratives evolve and take on new elements, as in Maricopa County and Detroit. Election workers in Los Angeles, for example, developed a crisis communications plan ahead of the 2021 gubernatorial recall election, identifying worst-case scenarios and stakeholders who could help share accurate information with specific communities. For election offices with fewer resources, standardized planning tools are available. For instance, the federal Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency offers incident response plans, infographics, and simulated disinformation scenarios.

Lesson #2: Networks facilitate the spread of falsehoods.

Our analysis showed that the dissemination of some election lies and falsehoods clusters around several online communities and important influencers. We used network analysis — a process that examines the relationships between individuals and groups — to show how many times each election denier in our data retweeted others between mid-August and the end of November. The result was a map in which each connection represented a retweet and clustering reflected key spreaders who retweet at the highest rates. Our network analysis showed that communities are clustered around notable “misinformation spreaders” who fuel viral rumors as they travel and grow online. The major nodes in the networks are also election deniers in different states — Mayra Flores in Texas, Mark Finchem in Arizona, and Doug Mastriano in Pennsylvania — pointing to the centrality of high-profile state messengers in networks that spread misinformation.

Recommendation: Social media platforms, public figures, and civic groups should push back against networks that peddle election misinformation and amplify content from election officials.

Our research shows how critical it is to pay attention to networks that nurture viral rumors and lies. It builds on Facebook’s finding in the wake of the January 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol that the social media giant had done too little to identify coordinated networks of actors peddling lies and calls for violence.

In future election cycles, social media platforms can analyze networks to better track misinformation trends and early indicators of harm. If an isolated election issue occurs on Election Day, platforms can limit false stories’ spread early in the viral process by slowing down related shares and reposts until information is checked for accuracy.

Political leaders, public figures, civic groups, and social media companies should also amplify accurate content from election officials so that it breaks through information silos and networks. If a local election issue spurs misstatements or turns into a false national narrative on or after Election Day, social media companies should amplify corrections from local election officials — even when local officials have low follower counts online. Platforms should promote and elevate content from local governments, secretary of state offices, and other authoritative election sources. The companies should also maintain open channels of communication with election workers as on-the-ground developments occur.

Lesson #3: Election deniers use different social media platforms in different ways.

The differences between the ways social media platforms are used underscore the importance of accounting for each platform’s distinct features and user base in devising a strategy to combat misinformation.

Our comparison of different social media platforms showed key differences in content and communities of users reflected in data from the Midterm Monitor. Compared with Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook, we found that Instagram had less election content, fewer false narratives, and less discussion of fraud. YouTube had the highest volume of discussions of fraud. Twitter and Facebook, meanwhile, both had a relatively high volume of false narratives about elections. The variation demonstrates that certain platforms play a greater role in misinformation about elections.

We also saw important differences in the kinds of content and candidates on platforms. Because of the nature of the platform, Twitter tended to feature shorter posts, but content was more likely to be reshared by a wider group. On Facebook, posts were longer in form, which allowed space for longer rants with more falsehoods. This suggests a difference in the way misinformation spreaders weaponize each of the platforms and the role that difference plays in perpetuating election falsehoods.

The conversation around elections on each of these platforms featured slightly different communities. Twitter had the most secretary of state candidates and seemed to be the center of the election security discussion. Each platform, moreover, has a different primary audience. According to other research, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to use Instagram and Twitter. Afro-Latino and Hispanic communities are more likely to use Instagram than the general population. These variations suggest that the content on each platform has different social implications.

Recommendation: A comprehensive strategy to combat misinformation should assess social media platforms’ distinct user communities and content, and it should incorporate news and civic organizations to reach broader groups.

The differences in the amount of false election content, user base, and content on each social media platform should be accounted for in crafting a comprehensive strategy for combatting misinformation on social media.

News and civic organizations can also reach broader groups and help stop rumors and lies from emerging and taking root. Journalists — including those with local, regional, and ethnic news outlets — can connect with local election offices and give voters context for innocent but disheartening glitches. Civic groups should give the public information in suitable languages and formats and act as a bridge between vulnerable communities, officials, and the media. When addressing lies and rumors, journalists and civic groups can provide accurate context, consult election experts, and use “no-follow” links to avoid boosting misinformation in search results.

• • •

Accurate voting information and trust in elections are critical to our democracy. A whole-of-society approach is needed to defend elections against the scourge of misinformation.