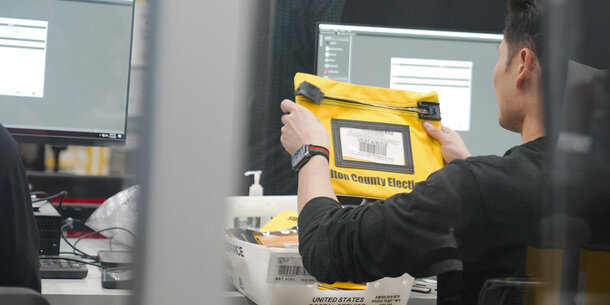

Election officials are confronting an extraordinary uptick in requests for access to sensitive election records and equipment.1 This trend is fueled by the spread of the lie of a “stolen” 2020 election. Requests for public records have flooded election offices, and both legislators and private litigants have attempted to use the subpoena process to obtain access.2 In rarer instances, rogue sheriffs have tried to seize equipment from election offices.3

This resource provides guidance to election officials who face requests for access to election records and equipment in their custody.

State laws providing access to public records are important for transparency, and election officials have a responsibility to fulfill requests. But some demands may go beyond what individuals are legally entitled to. Copying or providing access to election software and hardware, routers, and other associated equipment may pose security risks, and individuals may not have the legal right to access certain sensitive or confidential information, whether through a records request or civil subpoena. Police and sheriffs, meanwhile, typically have very limited legal power to seize equipment from election offices without a warrant.

When someone such as a lawyer, a judge, or a law enforcement official purports to have authority but makes what seems like a potentially illegitimate request for access or information, election officials may wonder what their options are. Some of the requests may be legitimate, but others may not be, and if accommodated, they may undermine the security of a jurisdiction’s election equipment.

When asked for sensitive records or equipment, election officials can and should respond in a way that complies with the law, protects staffers’ safety, and guards the security of our election systems. Three common scenarios and recommended plans of action are outlined below.

In all cases, election officials should consult with a competent attorney, including an attorney in their city or county legal department, as soon as possible. Where appropriate, they should also consult with their state’s association of local election officials, the office of their state’s chief election official, and other trusted and experienced election officials in their state. These officials may have advice on efficiently fielding similar requests, and sharing this information may help other officials facing similar situations. In particular, sham or rogue law enforcement activity is not common, and anyone engaging in this behavior may also be targeting other election officials.4

Endnotes

-

1

See Amy Gardner and Patrick Marley, “Trump backers flood election offices with requests as 2022 vote nears,” Washington Post, September 11, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2022/09/11/trump-election-deniers-voting/; see also Michael Wines, “Election Workers Face an Obstacle Course to Reach the Midterms,” New York Times, October 6, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/06/us/election-workers-midterms-polls.html. -

2

John Agar, “Kent County clerk objects to MyPillow founder’s demand for 2020 election records,” MLive.com, October 5, 2022, https://www.mlive.com/news/grand-rapids/2022/10/kent-county-clerk-objects-to-mypillow-founders-demand-for-2020-election-records.html. -

3

Peter Eisler and Nathan Layne, “Michigan sheriff sought to seize multiple voting machines, records show,” Reuters, August 30, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/article/usa-election-michigan-investigation-idCAKBN2Q01XM. -

4

Sue Halpern, “The Election Denier Who Tried to Prove ‘Stop the Steal,’” The New Yorker, September 7, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/american-chronicles/the-election-official-who-tried-to-prove-stop-the-steal (describing breaches of elections software in both Mesa County and Elbert County, Colorado, involving the same unauthorized persons).