A portion of a 1971 Supreme Court opinion sums up the intrinsic damage of Texas’s 2021 voter suppression law: “Sometimes the grossest discrimination can lie in treating things that are different as though they were exactly alike.”

The excerpt was quoted at closing arguments on Tuesday in LUPE v. Texas, a federal lawsuit challenging Senate Bill 1. Inside a San Antonio courtroom, attorneys argued that the law does not account for the social conditions in Texas that already set an unlevel playing field for people of color. The Brennan Center, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and other co-counsel challenged the law on behalf of voters, election administrators, community groups, civil rights and voting organizations, and faith-based groups for violating federal law and the Constitution.

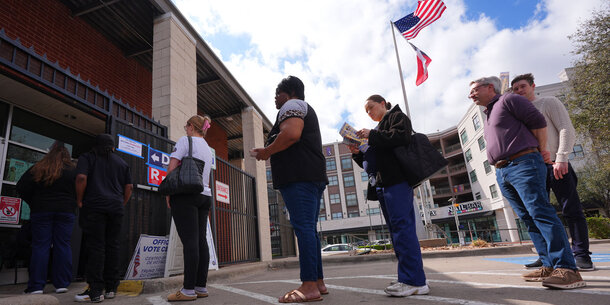

The arguments capped a nearly two-month trial that was held in the fall, when an array of witnesses testified about how the law saddles voters and election workers with significant burdens in a state where voting was already more difficult than most.

S.B. 1 imposes new restrictions on mail voting and hampers vote assistance for those who need it most, such as people with disabilities or limited English proficiency. It also curbs the ability of community and faith-based organizations to engage in nonpartisan voter outreach activities and puts election officials at risk of criminal prosecution for protecting voters from harassment by rogue poll watchers amid growing threats, intimidation, and violence.

Several of the law’s provisions make the franchise even more difficult to exercise, particularly for marginalized communities. For example, S.B. 1 bans drive-thru voting, an option that was particularly popular among voters of color during the Covid-19 pandemic. During the 2022 midterm elections, the first with S.B. 1 in effect, a single voter ID provision in the law led to disparate ballot rejections, with Asian and Latino voters more than 50 percent more likely than white voters to have a ballot rejected due to the new requirements. And for voters with disabilities, who often need help while voting, S.B. 1 now requires assisters to swear “under penalty of perjury” that the voter they are assisting “represented to me they are eligible to receive assistance” — layering unnecessary potential criminal penalties into the process.

Outside the courthouse immediately following arguments, Ray Shackelford of the Houston Area Urban League, spelled out how the nuanced restrictions of S.B. 1 work to disenfranchise voters.

“When you talk about access to transportation — how easy is it for people to get to and from the polls?” he asked rhetorically, as an example of the obstacles people with disabilities have to overcome before voting. “If someone is a shift worker — how realistic is it for them to be able to take off an hour or two when that could be the difference in paying your lights or putting food on the table?”

The law was part of a flood of anti-voter bills passed around the country, spurred by false claims of voter fraud after the 2020 election. Proponents of the legislation trumpeted lies and groundless conspiracy theories to claim that it would bolster election integrity. But Dana DeBeauvoir, a former Travis County clerk with over three decades of experience running elections, testified in September that alleged voter fraud is like “a unicorn.” It is “in the ones and twos out of millions of votes” and “in most cases unintentional.”

S.B. 1 sets itself apart from other voter suppression laws with its numerous provisions that harm election officials and workers in addition to voters. During closing arguments, Brennan Center attorney Leah Tulin zeroed in on one such measure, which makes it a crime for poll workers to “take any action” that would make a partisan poll watcher’s observation “not reasonably effective.” Tulin urged the court to block the poll worker provision as unconstitutionally vague, in violation of the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause.

Pointing back to the trial, Tulin noted that several county election officials, all with years of experience administering elections, told the court that after S.B. 1 was enacted, “they witnessed poll watchers behave in ways that made both election workers and voters feel uncomfortable, harassed, and intimidated."

“Poll watchers are being given the message from S.B. 1 that the law empowers them to decide whether their observation is effective,” she said, explaining that the poll watcher provision bases criminal liability on the subjective judgment of partisan poll watchers. As a result, election workers fear that they will face criminal penalties for trying to protect voters’ right to vote from disruptive or intimidating poll watchers.

A decision in the lawsuit is expected in the coming months.

Regardless of the outcome, the trial exposed the steep toll of Texas’s anti-voter law, which created unequal opportunities to vote. This fight is far from over, as Shackelford said after arguments concluded, “We still have a lot more work to do.”