This piece was updated on October 7 to add information about state and local restrictions on private militia groups and unauthorized security operations.

As Election Day nears, President Trump has increasingly threatened to instigate voter intimidation. First, he has insinuated that he will deploy law enforcement officers or call up the National Guard to root out election-related crimes at the polls. (Spoiler alert: voter fraud is vanishingly rare). The president has abused his authority over law enforcement before, most notably when he deployed federal agents — and threatened to deploy the military — in response to domestic protests earlier this summer.

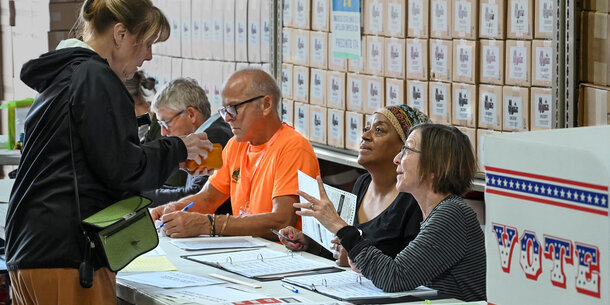

On top of this, in the first nationally televised presidential debate the president called for his supporters to “go into the polls and watch very carefully,” especially in Philadelphia. The Republican National Committee (RNC) claims to be gearing up for an aggressive “ballot security” operation involving 50,000 poll watchers, which many worry could include plans to intimidate voters. In 2017 a court freed the RNC from a 35-year-old consent decree that required the committee to obtain judicial approval of any such operations to ensure that they would not illegally intimidate or discriminate against voters or interfere with their right to vote.

There is a shameful history in parts of the country of armed officers, on duty or off, targeting Black voters and other voters of color for intimidation. Their mere presence in polling places could raise reasonable fears among groups that are frequently the target of racial profiling and police misconduct.

But the law is crystal clear: it is illegal to deploy federal troops or armed federal law enforcement officers to any polling place. State and local laws and practices place limits on the role of law enforcement and poll watchers. And a host of federal and state laws, many of which also carry severe criminal penalties, prevent anyone — whether a law enforcement officer or a vigilante — from harassing or intimidating voters.

The U.S. Military

Bottom Line: It would be illegal — and in many cases a federal crime — for the president to deploy the military to interfere with the election.

The Concern: President Trump has threatened to deploy the military to U.S. cities in response to protests; these threats have often been linked to his partisan attacks on Democratic mayors and governors. Although Trump has not explicitly said he would deploy troops to the polls, his threats to send in law enforcement echo his recent response to those protests. These threats, and Trump’s politicization of the military in other contexts, recently prompted two members of Congress to ask Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley whether he would obey an order to send active duty military to polling places.

Why It’s Illegal: Any deployment of troops or other armed federal agents to a polling place is a federal crime (unless the country is literally being invaded). The law, which dates back to 1948, says:

Whoever, being an officer of the Army or Navy, or other person in the civil, military, or naval service of the United States, orders, brings, keeps, or has under his authority or control any troops or armed men at any place where a general or special election is held, unless such force be necessary to repel armed enemies of the United States, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than five years, or both; and be disqualified from holding any office of honor, profit, or trust under the United States.1

Other federal statutes also prohibit the military from interfering in our elections.2 And the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 bars troops from being deployed on U.S. soil generally.3 There are exceptions to the law that Trump has tried to exploit, but they do not allow him to circumvent the explicit prohibition on using the military to interfere in elections.

In short, the president cannot deploy the military for any purpose connected to an election. The military knows this. A 2018 Defense Department directive confirms that military personnel “will not conduct operations at polling places.”4 Likewise, when asked by the two members of Congress whether he would send troops to polling places, General Milley made clear, “I do not see the U.S. Military as part of this process.” Any officers who try to cross this line could be prosecuted.

The Department of Homeland Security

Bottom Line: As with the military, it would be a crime for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to deploy any of its agents — including those from the Federal Protective Service, Customs and Border Protection, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) — in connection with an election.

The Concern: Over the summer, in response to civil unrest accompanying the wave of peaceful protests that followed the murder of George Floyd, the Trump administration recklessly deployed agents from the Federal Protective Service and Customs and Border Protection to Portland, Oregon, and other U.S. cities over the objections of state and local officials (a number of whom have filed lawsuits that are pending in federal court). The administration claimed that the agents had been deployed only to protect federal property, but they allegedly assaulted protesters and carried out arrests far from federal buildings. This history, coupled with the president’s recent threats, raises understandable fears that DHS forces might be deployed to intimidate voters.

False rumors are also now spreading about plans for ICE agents to patrol the vicinity of polling places and even arrest voters they suspect of being undocumented. Some of these rumors appear to have come from groups that are intentionally trying to suppress the vote among Latinos and other people of color. These rumors create real fear in communities ICE has targeted with increasingly aggressive tactics.

Why It’s Illegal: Any deployment of DHS agents in the vicinity of a polling place or any place where votes are being counted would violate the same criminal statute that applies to all armed federal officers. The Department of Justice’s own election crimes manual confirms that the statute bars any armed federal agent from election sites.5 Indeed, when asked about the president’s threat to send agents to the polls, the acting head of DHS responded point-blank: “We don’t have any authority to do that at the department.”

It is also illegal for anyone to intimidate or threaten voters, disenfranchise voters, or target voters based on their race or ethnicity — federal agents included. The use of federal agents to intimidate voters is a crime under section 11 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA).6 Courts have held that the law forbids tactics such as following alleged suspects, recording license plate numbers, and brandishing weapons.7 The consequence for an intentional violation? Up to five years in prison.8

Federal law also makes it a crime for people (including government officials) to conspire to deprive someone of the right to vote or the right to be free from discrimination.9 For this offense, violators face up to 10 years in prison. The Constitution too prohibits government officials (including ICE and other federal agents) from targeting voters of color for enforcement actions.10

Even aggressive DHS operations unconnected to an election may be out of bounds during the election. The Constitution limits otherwise legal federal law enforcement activities if they interfere with areas of fundamental state concern. For example, federal courts have blocked ICE agents from entering state judicial facilities to arrest undocumented immigrants because it disrupts states’ ability to operate their own court systems.11 The same logic would bar operations by ICE (or other parts of DHS) that could significantly interfere with a state’s ability to conduct a free and fair general election.12

The Department of Justice

Bottom Line: At the polls, the Department of Justice (DOJ) is limited to observing elections for compliance with federal voting rights laws for subsequent enforcement efforts. It cannot interfere with the voting process or send agents to investigate other laws.

The Concern: Attorney General Barr, who has frequently repeated the president’s lies about purported voter fraud, has asserted the right to send DOJ agents to the polls for a variety of reasons, including to investigate potential election crimes. His statements, coupled with the president’s own threats to have U.S. attorneys at the polls, have led to fears that Trump and Barr will seek to use DOJ’s authority to meddle in the election.

Why It’s Illegal: DOJ is subject to the same restrictions as other federal agencies, including the absolute bar on deploying armed agents to polling places or other locations where an election is being held. As the department’s own election crimes manual states, prosecutors have “no authority to send FBI special agents or [U.S. marshals] to polling places.”13 Even investigative activities anywhere near polling places require special permission.14

In short, Attorney General Barr, to the extent that he is asserting a right to deploy armed agents to the polls or other election-related sites while voting is ongoing, is simply wrong. If he did try to send armed agents to polling places during an election to investigate potential crimes or “enforce civil rights” (two pretexts he’s mentioned), he would be committing a federal crime. Legitimate election crime investigations should be conducted only after voting is complete, as typically happens, including most recently in the wake of revelations of absentee ballot tampering by a GOP operative in a 2018 North Carolina congressional race. Election Day disturbances should be handled by state officials.

While armed DOJ agents are not allowed at the polls, the department may under certain circumstances send unarmed representatives under its election observation and monitoring programs. These unarmed civilian federal employees are tasked only with observing and monitoring voting processes for compliance with the federal Voting Rights Act and the Help America Vote Act and reporting back to a court or DOJ’s Civil Rights Division.15 They have no power to enforce the law.16 In fact, monitors do not even have the authority to enter polling places without permission from state or local election officials.17 The federal observer program, which was severely limited by a Supreme Court decision that gutted a core provision of the Voting Rights Act,18 is now restricted to a small number of places where a court has ordered it (right now, just Evergreen, Alabama, and Pasadena, Texas).19

State and Local Law Enforcement

Bottom Line: State and local law enforcement can sometimes be at polling places, but never under orders from the president and always subject to numerous restrictions.

The Concern: The president’s threat to send law enforcement to the polls included local officials such as sheriffs. Even without such threats, the long history of discriminatory policing and official voter suppression in many places provides ample reason to worry that the presence of any law enforcement at the polls may intimidate some voters, especially voters of color.

What’s Legal and What Isn’t: The federal government, including the president, has no authority whatsoever over state and local law enforcement,20 and certainly no power to call them to the polls.

State and local law enforcement officers may have the right to be at the polls for the purpose of helping election officials ensure a safe voting environment. If, for example, private citizens try to interfere with the right to vote, election officials may call law enforcement in to protect the public and ensure no one is deterred from voting.

But there are a variety of legal restrictions placed on state and local law enforcement. In some states, including Pennsylvania and California, officers who show up to the polls without being called there by election officials have committed a crime.21 In a number of other states, including Florida, North Carolina, Ohio, and Wisconsin, officers at the polls must obey orders from election officials.22 And under no circumstances may state or local police intimidate voters, prevent people from voting, or target particular racial or ethnic groups. These are all violations of federal law.23 Many states also have their own robust voting rights protections.24

In practice, election officials and law enforcement typically develop plans ahead of elections to ensure that voting processes will be orderly and fair, including through intrastate working groups coordinated by election officials to game out and plan for a variety of scenarios.

The National Guard

Bottom Line: The president cannot deploy armed National Guard units to the polls or exert any control over units at the polls. There are also limits on states’ use of the National Guard, including the general prohibitions on intimidation and discrimination.

The Concern: As with the military and federal law enforcement, President Trump has misused his authority over the National Guard. His June deployment of eleven states’ guard units to counter protests in Washington, DC, was widely criticized. Given this history and the president’s recent statements, some worry about guard units being deployed to harass or intimidate voters or election officials.

What’s Legal and What Isn’t: National Guard units under federal command are part of the U.S. military,25 and so deploying them to the polls would be a federal crime, just like it would be for the other military branches. Moreover, using them for law enforcement purposes would in most circumstances violate the Posse Comitatus Act.

These prohibitions do not apply to guard units under the command of a state government. Some states, however, have laws of their own prohibiting the deployment of guard units to the polls. In California, for example, it is a misdemeanor for active-duty guard members (like other law enforcement officers) to enter voting locations in many circumstances.26 In every state, guard units under state command are also subject to the same federal and state voting rights and antidiscrimination laws as state and local law enforcement, which means that they would be subject to criminal penalties for voter intimidation or other forms of election interference.

During the primaries, in the face of a nationwide poll worker shortage due to Covid-19, several states did deploy guard units to serve as emergency election workers. Those units were generally unarmed and served as ordinary poll workers or performed other administrative tasks. Such a deployment, while appropriate in the case of last-minute emergencies, is generally a last resort; during the primaries the deployments came at the request and direction of election officials. There should be less need for similar deployments this November, as election officials have been working hard to recruit new poll workers. (In the event that guard members are needed to fill staffing gaps, they should wear civilian clothes and their duties should be limited to those of poll workers.)

Guard units may also be deployed in “hybrid” status, in which they serve a federal mission set by the president or secretary of defense (and are paid with federal funds) while remaining under state command and control.27 State governors, however, must consent to use their guards for the mission in question.28 Moreover, guard units in this status arguably act under the authority of the president or secretary of defense and therefore would still be subject to the criminal prohibition on federal military officers stationing “armed men” at the polls. Guard units in hybrid status are still subject to state laws limiting their use at polling stations, as well as all federal and state voting rights and antidiscrimination laws.

Off-Duty Law Enforcement

Bottom Line: Off-duty members of the military, National Guard, and law enforcement are entitled to vote in person, serve as poll workers, and engage in other democratic activities at the polls, but they must follow the same rules as other members of the general public.

The Concern: Decades ago, the Republican Party recruited off-duty police officers to show up to the polls armed and wearing official-looking uniforms to engage in so-called “ballot security” efforts targeting Black and Latino communities. As a result of the Democratic Party suing to challenge the practice, the GOP’s operations were monitored by a federal court for 35 years. In 2017 the court order that provided for that monitoring expired. This year, in the lead-up to the first presidential election free from such oversight, the Republican National Committee is reportedly preparing to send out tens of thousands of poll watchers. The concern is that history will repeat itself.

What’s Legal and What Isn’t: Poll watchers are allowed to monitor elections in most states. Off-duty military members and law enforcement may generally take part in such activities, and of course may also be at the polls to vote themselves.

But, as noted, voter intimidation and discrimination are illegal and often criminal. Many laws, such as the VRA, apply to private as well as governmental actors, and so would cover individuals who are off duty and acting in their personal capacities.

Many states also flatly prohibit openly carrying a gun into a polling place.29 Some states, including Texas, prohibit carrying concealed weapons as well.30 Many states prohibit weapons in specific types of polling places, such as government buildings.31 Others have specific rules against brandishing a firearm in a way that could intimidate voters.32

The tactics that the RNC used to intimidate Black and Latino voters are just as illegal today as they were in the 1980s. Anyone who knowingly engages in such tactics can and should face legal consequences.

Private Militias and other Vigilante Poll Watchers

Bottom Line: Voter intimidation by poll watchers is illegal, and there are legal restrictions on who can engage in poll watching and rules in place to ensure accountability.

The Concern: During the first presidential debate, President Trump called for his “supporters to go into the polls and watch very carefully,” and specifically suggested that they do so in Philadelphia. In the same debate, he told the Proud Boys, a violent extremist organization, to “stand by.” Especially in light of the expiration of the consent decree restricting the Republican Party’s “ballot security” operations, these statements have led to concerns of vigilante poll watchers engaging in voter intimidation.

Why It’s Illegal: Not just anyone can show up and watch the polls. Most states limit who can serve as a poll watcher, often to appointed representatives of a candidate or a party and, in some cases, to neutral, nonpartisan observers. In some states, such as Pennsylvania, poll watchers must be registered to vote in the county where they seek to observe the polls. These limits help deter misconduct and ensure accountability. In addition to limiting who can serve as a poll watcher, most states have strict limits on what poll watchers can do. States including Georgia, Florida, and Michigan prohibit poll watchers from speaking to voters.33 Many states allow poll watchers to challenge voter eligibility, but they must follow specified procedural and substantive limits. Poll watchers who abuse their roles may be ejected from the polling place.

State and local laws also restrict armed militias from appearing at the polls. Most states have laws or constitutional provisions prohibiting private groups from engaging in unauthorized paramilitary or law enforcement activities. Georgetown Law School’s Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection (ICAP) published a 50-state guide documenting the laws that state and local governments can use to stop private militias from engaging in paramilitary activities in public spaces.34

Armed groups or individuals who claim to offer security services at polling stations will also be in violation of state and local laws. Virtually all states have laws that strictly regulate the provision of private security services, particularly armed security services. These laws typically establish licensing and firearms-permitting procedures to ensure security guards are properly vetted, trained, and insured. Depending on the state, providing security services without a license can result in civil fines and/or criminal penalties.35

Even apart from all of these limits, both federal and state laws outlaw voter intimidation and conspiracies to prevent eligible Americans from voting, and election officials are prepared to respond and remove bad actors. State and local election officials also have plans and protocols in place to address any disruptions at the polls. Most have strengthened those plans as the threat level has increased. They will not be caught off guard.

Conclusion

Federal and state laws clearly prohibit any deployment of the military, law enforcement, or vigilantes to the polls to intimidate voters or engage in any operation unrelated to maintaining the peace while elections are being held. The president’s suggestions that law enforcement should act inappropriately or that vigilantes will storm the polls are simply designed to discourage voters, particularly voters of color, from voting and to undermine faith in our elections. It is important to call out Trump’s comments for what they are: not just calls for illegal action but also attempts at voter suppression. Voters should not be intimidated.

Endnotes

-

1

18 U.S.C. § 592. -

2

See 18 U.S.C. § 593 (punishing any officer of the military who seeks to “prescribe or fix . . . voter qualifications,” intimidate voters, or impose election regulations on a state “different from those prescribed by law”); 52 U.S.C. 10102 (“No officer of the Army, Navy, or Air Force of the United States shall prescribe or fix, or attempt to prescribe or fix, by proclamation, order, or otherwise, the qualifications of voters in any State, or in any manner interfere with the freedom of any election in any State, or with the exercise of the free right of suffrage in any State.”). -

3

18 U.S.C. § 1385. -

4

U.S. Department of Defense, Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA), Directive No. 3025.18, Mar. 19, 2018, 7, https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodd/302518p.pdf?v. -

5

Richard C. Pilger, ed., Federal Prosecution of Election Offenses, 8th ed., U.S. Department of Justice, December 2017, 9, https://www.justice.gov/criminal/file/1029066/download. -

6

52 U.S.C. § 10101(b) (2018); see also 18 U.S.C. § 594 (2018) (“Whoever intimidates, threatens, coerces, or attempts to intimidate, threaten, or coerce, any other person for the purpose of interfering with the right of such other person to vote or to vote as he may choose . . . shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than one year, or both.”). -

7

Democratic National Committee v. Republican National Committee, No. 81–3876 (DRD) (NJ 2009). -

8

52 U.S.C. § 10308. -

9

42 U.S.C. § 1985(3). -

10

U.S. Const. Amend. I, V, XV. -

11

See, e.g., State v. U.S. Customs and Immigration Enforcement, 431 F.Supp.3d 377, 392 (S.D.N.Y. 2019). -

12

One note of caution: if ICE agents try something illegal, poll workers and others should not take it upon themselves to call them on it. Anyone who tries to prevent an ICE agent from apprehending someone who may be in the United States unlawfully can themselves be held criminally liable, even if the agent is acting illegally. Anyone who witnesses ICE agents near the polls should immediately contact state and local election officials and immigrant and voting rights organizations — including by calling 866.OUR.VOTE, a nonpartisan voter protection hotline staffed by trained volunteers. -

13

Pilger, Federal Prosecution of Election Offenses, 9. -

14

Pilger, Federal Prosecution of Election Offenses, 9. -

15

Pilger, Federal Prosecution of Election Offenses, 85–86; and 52 U.S.C. §§ 10302(a), 10305(d). -

16

Pilger, Federal Prosecution of Election Offenses, 85n40. -

17

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, An Assessment of Minority Voting Rights Access in the United States, 2018, 268, https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/2018/Minority_Voting_Access_2018.pdf; cf. 52 U.S.C. § 10305(d) (authority to enter polling places granted to observers). -

18

See Shelby County, Ala. v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529, 557 (2013) (declaring coverage formula in 52 U.S.C. § 10303(b)); and 52 U.S.C. § 10305 (providing for observers in jurisdictions covered by the formula in § 10303(b)). -

19

Patino v. City of Pasadena, 230 F. Supp. 3d 667, 729–30 (S.D. Tex. 2017); and Allen v. City of Evergreen, Civil No. 13–107, 2014 WL 12607819, * 2 (S.D. Ala. Jan. 13, 2014). -

20

Printz v. U.S., 521 U.S. 898, 935 (1997) (“The Federal Government may neither issue directives requiring the States to address particular problems nor command the States’ officers, or those of their political subdivisions, to administer or enforce a federal regulatory program.”); see also New York v. U.S., 505 U.S. 144, 188 (1992). -

21

25 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 3520 (West 2020); Cal. Elec. Code § 18544 (West 2020); John Tanner, “Effective Monitoring of Polling Places,” Baylor Law Review 61 (2009), 60–61. -

22

Fla. Stat. Ann. § 102.031(2) (West 2019); N.C. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 163–48 (West 2020); Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 3501.33 (West 2020); and Wis. Stat. Ann. § 7.37(2) (West 2020). -

23

42 U.S.C. § 1983; 18 U.S.C. § 594. -

24

See, e.g., Fla. Stat. Ann. §104.0615 (West 2020); Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 168.733 (West 2020); Nev. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 293.710. -

25

10 U.S.C. §§ 10105, 10106 (2018) (“The Army National Guard while in the service of the United States is a component of the Army.”). Note that parallel statutes apply to the Air Force National Guard. -

26

California makes it a felony for any “person in possession of a firearm or any uniformed peace officer, private guard, or security personnel or any person who is wearing a uniform . . . in the immediate vicinity of . . . a polling place without written authorization of the appropriate city or county elections official.” Cal. Elec. Code § 18544 (West 2020); and Tanner, “Effective Monitoring of Polling Places,” 60–61. -

27

See, e.g., 32 U.S.C. § 502(f). -

28

See 32 U.S.C. § 502(f) (providing for duty on “operations or missions undertaken by the member’s unit at the request of the President or Secretary of Defense”). -

29

National Conference of State Legislatures, “Polling Places,” Aug. 18, 2020, https://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/polling-places.aspx. -

30

Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 46.03(a)(2) (West 2020). -

31

Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, “Location Restrictions,” accessed Sept. 28, 2020, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/gun-laws/policy-areas/guns-in-public/location-restrictions/. -

32

See, e.g., Pennsylvania Department of State, “Guidance on Rules in Effect at the Polling Place on Election Day,” 2016, 3 https://www.dos.pa.gov/VotingElections/OtherServicesEvents/Documents/DOS%20GUIDANCE%20ON%20RULES%20IN%20EFFECT%20AT%20THE%20POLLING%20PLACE%20ON%20ELECTION%20DAY%2010–16.pdf (“Individuals inside or outside the polling place who behave aggressively with a firearm or who ostentatiously demonstrate that they are carrying a firearm and that behavior either is intended to or has the effect of intimidating voters will be removed, reported to the appropriate authorities for investigation and prosecution.”). -

33

Ga. Code Ann. § 21–2–408(d); Fla. Stat. Ann. § 101.131(1); and Michigan Department of State Bureau of Elections, The Appointment, Rights and Duties of Election Challengers and Poll Watchers (Sept. 2020), 12, https://www.michigan.gov/documents/SOS_ED_2_CHALLENGERS_77017_7.pdf. -

34

“Prohibiting Private Armies at Public Rallies: A Catalogue of Relevant State Constitutional and Statutory Provisions,” Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection, September 2020, https://www.law.georgetown.edu/icap/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2018/04/Prohibiting-Private-Armies-at-Public-Rallies.pdf. ICAP has also published fact sheets for every state with recommendations for the public regarding what to do when private militias are observed near polling places. “State Fact Sheets,” Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection website, https://www.law.georgetown.edu/icap/our-work/addressing-the-rise-of-unlawful-private-paramilitaries/state-fact-sheets/. -

35

Links to each state’s licensing procedures and regulations can be found at websites promoting security guard licensing and training courses, such as securityguard-license.org and securityguardtraining.com.