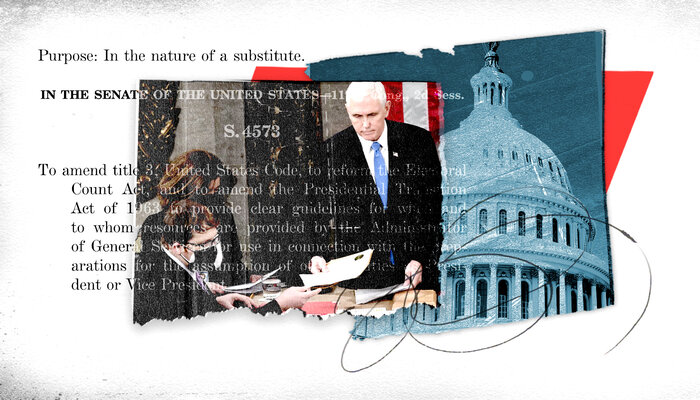

In December 2022, Congress passed the Electoral Count Reform Act to overhaul the poorly drafted 1887 Electoral Count Act, which governs the process of appointing presidential electors and tallying their votes. The law seeks to fix confusing and ambiguous provisions in the original law that helped pave the way for the unprecedented attempt to overturn the 2020 presidential election, culminating in the January 6 assault on the Capitol.

What is the Electoral College, and how many votes are needed to win?

The Electoral College is the body that elects the president and vice president of the United States every four years. It is established by Article II of the Constitution, which also provides that each state may select a number of electors equal to the number of its U.S. representatives and senators. The 23rd Amendment, ratified in 1961, assigns three additional electors to the District of Columbia, bringing the total number of electors to 538. To win, a presidential ticket must obtain a majority — 270 if all electors vote. Otherwise, the 12th Amendment provides that the House of Representatives chooses the president, with each state delegation receiving one vote, and the Senate chooses the vice president by majority vote.

Under the Electoral Count Reform Act, if the number of electoral votes cast decreases (e.g., because Congress votes to sustain an objection and not count a slate of electors, as described below), the number of votes needed to win also decreases. For example, if Congress discards 10 electoral votes, the total number of votes cast drops to 528, and the number of votes needed to win drops to 265. This reduces the incentive for supporters of a losing candidate to try to throw out electoral votes so that Congress can select the president. In the aftermath of the 2020 election, some Trump supporters hoped that if they could get Joe Biden’s electoral votes below 270, then the House could install Trump as president.

How do states choose electors?

Every state and the District of Columbia currently select electors by popular vote. A vote for a presidential ticket is thus technically a vote for the electors who have pledged to vote for that ticket (usually individuals selected by the political parties). The Electoral Count Reform Act makes clear that a state may not change its method of selecting electors after Election Day — in other words, state legislatures have no authority to set aside election results they do not like and choose electors by some other means, as some claimed they had the power to do following the 2020 vote.

The new law also bars a presidential election from being postponed past Election Day — set by statute as the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November — an idea Trump floated in the run-up to the 2020 vote. The law does allow states to extend voting for presidential candidates past Election Day, but only in extraordinary and catastrophic circumstances, such as a major natural disaster or terrorist attack.

Once state officials tally and certify presidential election results, the state’s “executive” must issue a “certificate of ascertainment” formally appointing the winning slate of electors no later than six days before the members of the Electoral College vote in mid-December.

Before the Electoral Count Reform Act, it was unclear which state officials had the power to appoint electors. Many states have multiple elected executive officials, and the law also seemed to leave open the possibility of state legislatures themselves appointing electors, as noted above. That created the potential for states to appoint multiple seemingly valid slates of electors in the event of a disputed election.

The reform act fixed this problem by making clear that “executive” refers to a state’s governor (and the mayor of Washington, DC) unless state law provides otherwise. The certificate issued by the governor or other legally designated official is “conclusive” unless ordered revised by a lawful court order, in which case the court-ordered revised certificate supersedes the prior one. These changes greatly reduce the possibility of a state sending more than one facially valid slate of electors to Congress.

What happens if there is a dispute about who won the election?

Of course, there are likely to still be disputes as to who won, particularly in closely divided battleground states. As in the past, these will for the most part be resolved in court. The Electoral Count Reform Act changed very little about this process, with one exception: if a candidate for president or vice president sues in federal court to challenge the issuance or failure to issue a certificate appointing electors, the case will go to a special three-judge federal court, with the possibility of an appeal straight to the Supreme Court. This expedited process is intended to create a mechanism for outcome-determinative lawsuits to be resolved before the electors meet to cast their votes.

How do electors vote?

The Electoral College “meets” on the first Tuesday after the second Wednesday in December (the Electoral Count Reform Act moved the meeting one day later than under the original law). The Electoral College does not literally meet as a single body. Rather, each state’s electors gather in their state capitol to cast their votes. They then transmit those votes, together with copies of the certificates of ascertainment appointing them, to the president of the U.S. Senate (i.e., the vice president), state officials, and the archivist of the United States.

Previously, each state’s executive was required to ratify their electors’ appointments and then transmit them to the archivist, who in turn passed them on to Congress. This created the risk of an executive refusing to transmit their state’s certificate of ascertainment or the archivist (who is appointed by the president) failing to transmit it. The new law ensures that the votes of each state’s electors will go directly to Congress.

Notably, the Constitution does not bind electors to vote for the winner of their state’s popular vote, notwithstanding state law. Thirty-three states and the District of Columbia require electors to vote as they are pledged to: for the popular vote winner. Among these states, 14 provide for electors who vote against their pledge — so-called “faithless electors” — to be removed or for their votes to be nullified (the Supreme Court upheld such laws in a 2020 unanimous ruling). Voting by faithless electors has been a regular occurrence in presidential elections since states first started selecting electors by popular vote, although to date, no faithless elector has ever determined the result of a presidential election.

How does Congress count the electoral votes?

On January 6, following the presidential election and the Electoral College meeting, Congress convenes in a joint session to count and certify the electoral votes, as the 12th Amendment requires. The Senate’s presiding officer, typically the vice president, leads the joint session and is responsible for opening votes and announcing the final results. The actual counting is done by “tellers” — members of the House and Senate appointed by the majority and minority parties.

As the vice president announces the electoral votes, members can object to them in writing. Upon receipt of a valid objection, the chambers separate and debate the objection for up to two hours before voting on it. Each objection is entitled to a separate period of debate and its own vote. To be sustained, an objection requires majority support in both chambers.

Under the original 1887 law, it only took one senator and one representative to force debate on an objection, creating the potential for prolonged delays. After the 2020 election, for instance, members lodged baseless objections that forced the two houses of Congress to debate until nearly 4 a.m. (notwithstanding that violent insurrectionists had just stormed the Capitol). The possibility of a state sending multiple facially valid slates, and confusing rules as to what would happen if the chambers tried to count different slates, added to the potential for chaos.

The Electoral Count Reform Act addressed these problems by raising the threshold for consideration of an objection to one-fifth of each chamber. Under this threshold, the objections lodged in 2020 would have failed because they would have fallen short of the 20 senators needed to sign. As noted, the new law also largely eliminated the possibility of a state sending more than one seemingly valid slate of electors. For such a slate not to count, both chambers would have to vote to discard it by sustaining an objection.

What is the vice president’s role?

The Electoral Count Reform Act eliminates any doubt that the vice president’s role in the electoral count process is primarily ceremonial. In the aftermath of the 2020 election, Trump and his allies — most notoriously, former law professor John Eastman — argued that as presiding officer, Vice President Mike Pence had the power to unilaterally reject electoral slates and throw the election to Trump. While Eastman reportedly admitted in private that this argument was bogus, he and Trump both repeated it publicly many times. Pence’s refusal to go along with the plan led to him being one of the main targets of the January 6 attack on the Capitol, with many participants carrying a makeshift noose and chanting “hang Mike Pence!”

The law clarifies what was already evident to most legal observers: the vice president’s role in the joint session is limited to “ministerial duties,” and she or he does not have the authority to determine the validity of electoral votes or otherwise “adjudicate or resolve disputes.”

Is the Electoral Count Reform Act enough to safeguard our democracy?

No. The legislation’s passage was necessary, but it addresses only one of the vulnerabilities that contributed to January 6. There is still an urgent need for broader democracy reforms to guard against attempts to sabotage the electoral process, secure voting rights, and address other pressing challenges for American democracy. The Freedom to Vote: John R. Lewis Act, which passed the House last year but was stopped in the Senate because of the filibuster, would have addressed many of these issues. Passage of that bill or a similar one must remain a priority.