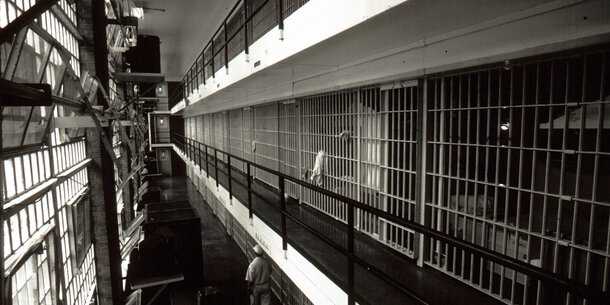

On July 1, Congress passed a budget bill that gives an unprecedented $45 billion for building new immigration detention centers, including family detention facilities. This massive increase in detention beds across the country comes at a time when there is increasing concern about detention conditions for undocumented children.

The provisions of the bill raise questions about the treatment of families facing deportation proceedings. It also does not align with — but does not supersede — the Flores settlement, the 1997 legal agreement addressing the treatment of immigrant children in U.S. custody.

Does ICE put families into detention?

In 2021, the Biden administration effectively halted the practice of holding families with children in immigration detention, which was common during the first Trump administration. In lieu of detention, the Biden administration relied on alternatives to detention, such as electronic monitoring and case-management programs, so families with children did not need to be held inside detention facilities. By many measures, alternatives to detention have been successful. In one program, for example, 99 percent of families complied with their immigration check-ins, and the cost was significantly less than detention.

The Trump administration is not only bringing back widespread family detention — it has made changes that will increase the number of immigrant children taken into federal custody. The administration is ending programs for people lawfully paroled into the country and terminating the Temporary Protected Status designation for people from Afghanistan, Cameroon, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. And it changed its policy to allow arrests in places that had been considered off-limits to law enforcement, such as churches, schools, and immigration court hearings.

Who is in family detention?

In the immigration context, “families” are primarily mothers with their children. Fathers are usually already separated from the rest of the family and housed in adult facilities. Even when children are detained with their mothers, public health experts have shown that detention has serious physical and mental health consequences. One study of conditions in Texas’s now-reopened Karnes County family detention center found inappropriate screening and follow-up care for existing chronic medical conditions, malnutrition, tuberculosis, and inappropriate mental health screening. They concluded that “there is no humane way to detain children and no version of family detention that is acceptable.”

Even so, the report recognized that children are likely to continue to be held in detention, and it made several recommendations: Children with acute medical needs must be treated by medical personnel with an appropriate level of training and expertise in pediatrics. Children should be screened and treated for illnesses that spread easily in detention settings, such as tuberculosis and flu. And children need appropriate screening and treatment for malnutrition.

Are children in immigration detention receiving adequate care?

It is hard to assess the treatment of undocumented children in federal custody because the administration has resisted oversight of detention centers, including those that hold children. The administration has effectively shuttered internal offices at the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) that monitored detention conditions in real time. The Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties has documented abuses of due process, excessive or inappropriate use of force, and sexual abuse or assault in ICE detention. But whistleblowers at that office have reported that more than 500 open investigations have been halted.

A DHS spokesperson said the Office of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman is being streamlined to “remove roadblocks to enforcement.” In addition to investigating more than 10,000 formal complaints in a year, that office conducted routine inspections of detention facilities, helping prevent problems before they happened. DHS’s inspector general investigations lag by months or even years.

Outside of internal DHS oversight and oversight from the courts, Congress also performs a critical oversight role, but the administration has blocked congressional personnel from their legal entitlement to visit facilities.

What is the Flores settlement?

The Flores settlement is a 1997 legal agreement that creates specific protections for immigrant children in custody in the United States. Its provisions include the following requirements:

- Children should be released to a family member or another responsible adult as soon as possible.

- Conditions must be safe and sanitary.

- Children should be held in the least restrictive setting possible.

- Facilities must give children access to toilets and sinks, drinking water and food, medical assistance if the minor needs emergency services, adequate temperature control, and ventilation.

- There must be adequate supervision to protect minors from others.

- Children must have contact with family members.

The settlement is currently overseen by Judge Dolly Gee of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California. All ICE family detention centers are also required to follow ICE’s internal 2020 Family Residential Standards, but internal DHS watchdogs collected and investigated allegations that these rules were being violated, and the government recently admitted that they have privately modified those standards.

Does the Flores settlement still govern the treatment of undocumented children in custody?

The Biden administration passed new regulations for migrant children in the United States without an adult who are in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services; it terminated the Flores settlement only as it applied to that department, with the exception of children in restricted facilities.

So far, the terms that apply to ICE are still in effect. But in May, the Trump administration’s Department of Justice filed a motion to terminate the Flores settlement agreement altogether. The department argues that recent legislation, along with agency policies and regulations, render the agreement unnecessary.

A group of immigration lawyers challenged the federal government’s effort to end the Flores settlement agreement, and in August, Judge Gee ruled that the government had not identified new facts or law that warrant terminating the settlement. The challengers submitted interviews with detainees at two facilities that detailed human rights concerns. For example, of the 90 families that the immigration advocacy group RAICES interviewed in the facilities, 40 spoke of medical neglect. In one case, a nine-month-old child reportedly lost eight pounds during one month in detention.

Who will be responsible for the new detention facilities?

Mostly for-profit firms.

Even before Congress passed the law increasing immigrant detention beds, ICE had already signed contracts with two private prison firms to bolster the country’s capacity to house undocumented children and families. Existing facilities were set to grow, and centers that the Biden administration had shuttered would reopen. This was in response to significantly expanded detention. As of June 29, 2025, there were 57,861 detainees in ICE facilities compared to 38,265 detainees in June 2024, an increase of 51 percent that leaves these facilities nearly 45 percent above their capacity. About 90 percent of detainees in immigrant detention facilities are already housed in centers managed by for-profit firms.

On March 5, CoreCivic — one of the largest private prison firms in the country — announced it was reopening the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas, to house 2,400 undocumented immigrants, many of whom are young children. The detention center had held families under both the first Trump administration and part of the Biden administration, but by the time it closed in 2024, it only held adults. CoreCivic will receive a guaranteed payment each month to manage the facility, and it expects to earn $180 million in annual revenue once the center is fully operational.

Also in March, Geo Group, the for-profit firm with ties to Trump border czar Tom Homan and Attorney General Pam Bondi, agreed to transition the Karnes County Immigration Processing Center from housing only adult males to housing mixed populations. Like the South Texas Family Residential Center, Karnes also housed undocumented families during the first Trump administration until President Biden ceased the practice. Geo Group is expected to generate approximately $79 million in annualized revenues in the first full year of operations.

CORRECTIONS: A previous version of this explainer referred to a 20-day limit on the detention of children. While the government told the Flores court that children could be transferred to a licensed facility within 20 days, that limit isn’t codified in the settlement itself. Additionally, the piece originally stated that the July 2025 budget bill calls into question the status of Flores. While some commentators have raised concerns, the Flores settlement remains in effect.

UPDATE: This explainer has been updated to include recent developments in the legal challenges against the government’s effort to end the Flores settlement.