Part of

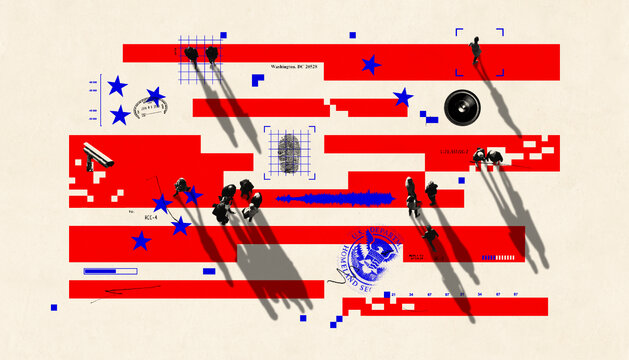

In the wake of 9/11, Congress established a new cabinet agency with a singular mission: to keep the country safe from terrorism. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) brought together 22 agencies with disparate functions under one roof. Two decades on, it struggles to carry out its work effectively and equitably.

Experts and advocates have scrutinized recurring abuses in DHS’s enforcement of immigration law and proposed robust reforms.1 DHS’s counterterrorism initiatives, by contrast, often operate under the public’s radar. So, too, do its travel and immigration screening programs. Yet these activities touch the lives of millions of Americans every day.

The department has aggressively targeted Muslims, communities of color, and social justice movements in the name of security. It conceals information about its vast databases and intrusive surveillance technologies. And it often embarks on ventures that implicate Americans’ privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties without even establishing or measuring their usefulness.

These problems have long festered due to a dangerous combination of broad authorities, weak safeguards, and insufficient oversight. The Trump administration brought them to the fore. DHS agents enforced the president’s ban on travelers from half a dozen Muslim-majority countries, wrenched children from parents at the southern border, escalated violence at protests from Washington, DC, to Portland, Oregon, spied on journalists and activists, and menaced immigrant communities from New York to New Mexico.

For most of its existence, DHS focused too narrowly on so-called international terrorism. It construed this mandate to include the activities of American Muslims, regardless of whether they had connections to foreign terrorist groups.2 Only belatedly is DHS turning its attention to domestic terrorism, particularly far-right political violence. In 2021, Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas announced that the department will increase grants for state and local governments and add a division to its intelligence arm.

But simply shifting its focus is not enough. The Biden administration has yet to critically evaluate the department’s post-9/11 missteps or fix the systems that have entrenched them. A course correction is critical.

With the Homeland Security Act of 2002, Congress tasked the new department with keeping the country safe from terrorist attacks. But DHS is far from the sole federal agency with a counterterrorism mission. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the National Security Agency (NSA), and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, among other agencies, carry the lion’s share of responsibility for it. DHS carved out a role for itself in two main areas: partnerships with state, local, tribal, and territorial authorities and screening of travelers and immigrants.

Section I of this report identifies the agency’s counterterrorism collaborations with state and local authorities and private firms. These programs have routinely surveilled American Muslims, traumatizing entire communities and casting them as hotbeds of terrorism. DHS agents have deployed these very tools against protestors, activists, and journalists.

Section II turns to travel and immigration screening programs. DHS has accumulated vast stores of information about people who travel into, out of, and over the United States. The Transportation Safety Administration (TSA) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP), among other DHS components, use this data to draw inferences about them, document their movements, and subject them to warrantless searches and interrogations. Agents do all of this without suspicion of potential wrongdoing. Unsurprisingly, reports of religious or ethnic profiling are common.

Section III analyzes DHS’s oversight infrastructure. Three primary offices — the Privacy Office, the Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL), and the Office of Inspector General (OIG) — have curbed some of the department’s transgressions. But they have allowed many other civil rights and civil liberties violations to continue.

Finally, this report identifies five avenues for reform: stronger safeguards against profiling; better protections for privacy and free expression; rigorous evaluations of program efficacy; meaningful transparency about data holdings and the implications DHS programs have for civil rights and civil liberties; and more robust internal oversight. Forthcoming Brennan Center reports will delve into these recommendations in greater detail.

The secretary of homeland security can — and should — make these changes now. The ease with which President Donald Trump weaponized DHS against both immigrants and citizens demonstrates that there are not sufficient safeguards against abuse. It is time for DHS to rein in its discriminatory and ineffective approaches and prevent new ones from being institutionalized.

Endnotes

-

1

A substantial amount of discussion in this report involves harms to Americans. The authors recognize the significant and detrimental consequences of DHS activities for immigrant communities and travelers of other nationalities. This report is not meant to diminish those harms but rather to fill what we perceive to be a gap in policy discussions regarding DHS. -

2

In the last two decades, the U.S. government has often treated the actions of individuals in the United States said to be influenced by groups like al-Qaeda and ISIS as international terrorism, even absent any indication of operational links or other concrete connections, on the theory that they promoted a common “foreign” ideology.

More from the Reform Agenda for the Department of Homeland Security series

-

Holding Homeland Security Accountable

Reforms to focus DHS’s work and guard against overreach depend on strengthened internal oversight offices. -

Overdue Scrutiny for Watch Listing and Risk Prediction

Programs that determine people’s ability to travel are rife with civil liberties abuses, and the government has not demonstrated that they keep Americans safe. DHS must adopt transparency and accountability measures. -

A New Vision for Domestic Intelligence

The Department of Homeland Security needs new rules and stronger oversight to better protect civil rights and civil liberties.