Pretend a state prison devises a new rule: “Prisoners who misbehave will be starved.” Would that be legal? More than 30 years ago, the Supreme Court answered that question, and it said no. Depriving a prisoner of life’s basic human necessities — like “food, warmth, and exercise” — crosses a constitutional line. But today’s Court apparently takes a different view.

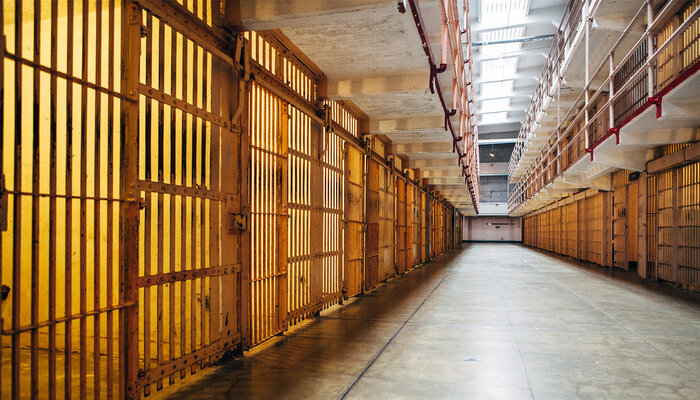

For three years, Michael Johnson, a former Illinois prisoner classified as “seriously mentally ill,” spent nearly every minute of every day entirely alone in a windowless enclosure no bigger than a parking spot. Denied virtually all contact with human beings, he’d been thrown in solitary confinement as punishment for poor behavior, and his only break from “the box” came just once a week for a 10-minute shower.

Mountains of research stretching back to the 19th century establishes that solitary confinement, which can last for months, years, and even decades, takes a devastating toll on the human psyche. And for people who struggle with mental illness like Johnson, it can be ruinous. So it’s little wonder that Johnson developed hallucinations, picked compulsively at his own flesh, and slathered himself and the walls of his cell with his own urine and feces. He also frequently attempted suicide. Sometimes he’d misbehave, he said, just to incite corrections officers into beating him.

Johnson longed to exercise; he thought it might help allay the manifestations of his declining mental health. But there was just one problem: he couldn’t.

His cell was too cramped for any real movement. And because the misconduct that landed Johnson in solitary persisted (which he attributes to his mental illness), prison officials punished him still more. They rescinded the one hour of out-of-cell exercise time usually offered five days a week to Illinois solitary prisoners.

Johnson sued the prison officials. Denying an incarcerated person exercise as punishment for misbehavior, he argued, is out of bounds under the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. His case eventually wound up on the Supreme Court’s doorstep, and his prospects seemed promising. On his side were a dozen former corrections directors and experts, a slew of medical professionals, the rulings of five federal appeals courts, and the Court’s own precedent. And yet a majority of the justices spurned Johnson’s petition nonetheless.

Fortunately, the quest to curtail solitary confinement, which ensnares tens of thousands of people across the country on any given day, can happen without the high court. Advocates can take the fight to check the punishment to elected federal, state, and local officials.

State and local leaders are particularly well placed to temper solitary confinement. After all, just over 90 percent of the nation’s total incarcerated population of nearly two million resides within jails and prisons that are run by state and local governments.

Since 2009, 42 states have established laws restricting or eliminating solitary confinement. Some states, like New York, Pennsylvania and Louisiana, have banned the punishment for whole classes of people including children, those with serious mental illness, members of the LGBTQ+ community, and pregnant people. Other states, including Connecticut and New Jersey, have statutorily capped the amount of time a person can be isolated — a reform hewing to one of the United Nations Nelson Mandela Rules providing that 15 continuous days or longer in solitary constitutes torture. Still other states, like Washington and Maryland, have empowered independent oversight bodies to assess implementation of laws reforming extended isolation.

Congress has made some changes too. In 2018, the bipartisan First Step Act eliminated solitary confinement in federal prisons for young people except for those posing immediate, physical risks. And last year, Senate and House members introduced the End Solitary Confinement Act, which would largely restrict segregation in federal institutions and offer incentives to states and localities to follow suit.

Some critics might argue that prolonged solitude is necessary for prison and jail order. That is misguided. While running prisons and jails is no doubt challenging and requires flexibility, scant penological evidence indicates that this harsh method of social control boosts the long-term safety of prisons and jails or that a regime without it would lead to greater violence. In fact, to hear the experts tell it, correctional leaders and staff can and should address repeated disruptive behavior by investing in alternatives to long-term solitary, like tailored treatment and programming aimed at people’s specific needs.

Nearly a decade ago, now-retired Justice Anthony Kennedy bemoaned a citizenry that “too easily ignore[s]” the panoply of shuddersome conditions reigning in the country’s prisons and jails. So the ultimate question seems not so much whether solitary, this prison-within-within-a-prison often dubbed “worse than death,” belongs in the warden’s toolbox. It’s whether we as a civil society even care about the monstrosity of an incarceration system that has grown too large to humanely operate.