Rolling Back the Post-9/11 Surveillance State

Restoring key privacy protections will benefit both national security and civil liberties.

Part of

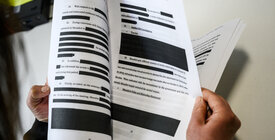

Six weeks after the attacks of 9/11, Congress passed the USA Patriot Act. The 131-page law was enacted without amendment and with little dissent three days after its introduction. It was the opening volley in a series of measures that vastly expanded the U.S. government’s ability to conduct domestic surveillance. Over the same period, dramatic advances in technology further bolstered the government’s spying powers and rendered decades-old legal protections obsolete.

As a result of these changes, we have seen a transformation, in two short decades, from a legal framework that requires the government to obtain a warrant when acquiring Americans’ most sensitive data to one that allows the government to amass such information without any suspicion of wrongdoing whatsoever. We also have seen the results. Easy governmental access to the private lives of law-abiding citizens has proven to have scant national security benefit, while enabling the monitoring of racial and religious minorities, protesters, and political opponents.

It is time for a course correction.

To ascertain the path forward, we must look to our nation’s past. In the early decades of the Cold War, there were few legal checks on the government’s surveillance powers. The FBI, CIA, and NSA exploited this license to spy on social justice activists — most famously, Martin Luther King Jr. — and anti-war protesters. At the height of these activities, many Americans were afraid to fully express their political views, even in private communications, for fear of government snooping and retaliation.

When the Senate’s Church Committee revealed these abuses, Congress and government agencies responded by enacting laws and policies to limit surveillance. They shared a common feature: Law enforcement and intelligence agencies could not collect information about Americans unless there was individualized, fact-based suspicion of wrongdoing. The level of suspicion — for example, “probable cause” or “reasonable basis to believe” — could vary depending on the context and the information’s sensitivity. But there could be no suspicionless surveillance.

This rule served to protect not only privacy, but also civil rights and First Amendment freedoms. It is much harder for government agents to target people based on their own racial or political bias (whether conscious or subconscious) if they must point to facts indicating likely criminal activity.

Of course, the system wasn’t perfect. It succeeded, however, in significantly constraining the government’s improper domestic spying. And it did so without negatively affecting national security. The 9/11 Commission found fault with many of the government’s practices, but it never suggested that the government should collect more information about people in the United States with less basis for suspicion.

After 9/11, the legal protections against suspicionless surveillance were swiftly and systematically cast aside. In a variety of contexts, it became lawful for the government to collect an American’s sensitive information based merely on a claim that the information was “relevant” to a legitimate purpose, regardless of whether the person was reasonably suspected of wrongdoing. Even for the most sensitive of information, communications content, Congress gave the NSA free rein to collect phone calls, texts, and emails between foreign targets and Americans — communications that previously could not be obtained domestically without a court order based on probable cause.

At the same time, technological advances created fertile new avenues for suspicionless collection. Smartphones, for instance, keep detailed track of Americans’ whereabouts — data that can be fed into sophisticated computer algorithms to determine a person’s associations, activities, and even beliefs. Courts were slow to recognize the sensitivity of this data, and until quite recently, the government could force cell phone companies to turn over any such information deemed “relevant.”

In 2018, the Supreme Court finally held that the government needs a warrant to obtain cell phone location information. Incredibly, the government interprets this ruling to apply only when it compels companies to disclose the data — not when it purchases the data from a willing seller. While there are statutory restrictions on phone and internet companies selling customer data to government agencies, there are no such restrictions on many types of app developers, because these entities didn’t exist when the relevant laws were passed. Moreover, any company is free to sell location information to a digital data broker, which can resell it (at a handsome profit) to the government — basically laundering the data through a middleman.

In addition, technology and globalization have eroded the distinction between domestic and overseas surveillance. There are few statutory constraints on the government’s ability to conduct surveillance abroad, yet such surveillance increasingly sweeps in the data of Americans. Moreover, the notion that foreigners have no privacy rights has become untenable. European courts are requiring U.S. companies to protect EU citizens’ data against broad U.S. government access — something companies cannot do under current U.S. law — as a condition of doing business with European companies.

In short, it is even easier today than it was in J. Edgar Hoover’s time for the U.S. government to collect sensitive information about Americans and foreigners alike. It should come as no surprise, then, that we have seen a return to some of the abusive practices of that era. After 9/11, the FBI developed a system of “ethnic mapping” and broadly infiltrated mosques, tasking informants with relaying attendees’ conversations. Since at least 2015, federal agencies have closely monitored Black Lives Matter protesters’ social media posts, tracked their protest activity, and, in at least one instance, opened intelligence files on journalists covering racial justice protests. Just last month, we learned that the Trump Department of Justice obtained the communications metadata of Democratic lawmakers and their family members, including a child.

Also unsurprisingly, there is zero evidence that suspicionless surveillance has made us safer. Consider the NSA’s program of “bulk collection” — the poster child for suspicionless surveillance — in which the agency obtained Americans’ phone records en masse. Two independent reviews found that this program yielded little-to-no counterterrorism benefit. Indeed, there is evidence that overcollection is counterproductive. Multiple government reviews of domestic terrorist incidents have found that agents missed signs of trouble because those signs were lost in the noise of irrelevant data.

A comprehensive overhaul of surveillance laws is in order. The goal should be reviving the requirement of individualized, fact-based suspicion for collection on Americans and others in the United States, while narrowing the permissible scope of collection on foreigners overseas. Achieving this goal will require restoring limitations that were stripped out of the law after 9/11, as well as enacting new ones to ensure that Americans’ sensitive information is protected from disclosure regardless of who holds the information or the technology used to capture it.

This is, without question, a tall order. It is also imperative. The past 20 years have given us a glimpse of what the future could hold. In the next 20 years, depending on what steps we take now, the United States can become a surveillance state in the mold of China — or we can realize our aspirations to be a country in which people of all races, ethnicities, religions, and political beliefs are free to live their lives and speak their minds without fear.

More from the 9/11 at 20 series

-

Training to Fight in the Light

9/11 showed how overreliance on secrecy can be dangerous. That’s even more true today. -

How to Combat White Supremacist Violence? Avoid Flawed Post-9/11 Counterterrorism Tactics

Attempts to expand government powers and to predict violence based on beliefs remain ineffective. -

Courts Have Been Hiding Behind National Security for Too Long

Racial and religious minorities have suffered from judicial deference to post-9/11 claims of national security.