Since the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United ruling ushered in a new era of big money in politics, congressional party finances have dramatically shifted. The parties now increasingly rely on loosely regulated shadow parties with close ties to congressional party leaders and comparatively less on official party committees.

And a new Brennan Center analysis shows that so far in the 2018 cycle, the trend is intensifying.

Here’s why this matters:

- Shadow parties use super PACs to raise unlimited contributions. In fact, their revenue comes overwhelmingly from massive contributions larger than the median American household’s income. By contrast, contributions to official party committees are limited, and the committees tend to raise around a third of their money from small donors of $200 or less.

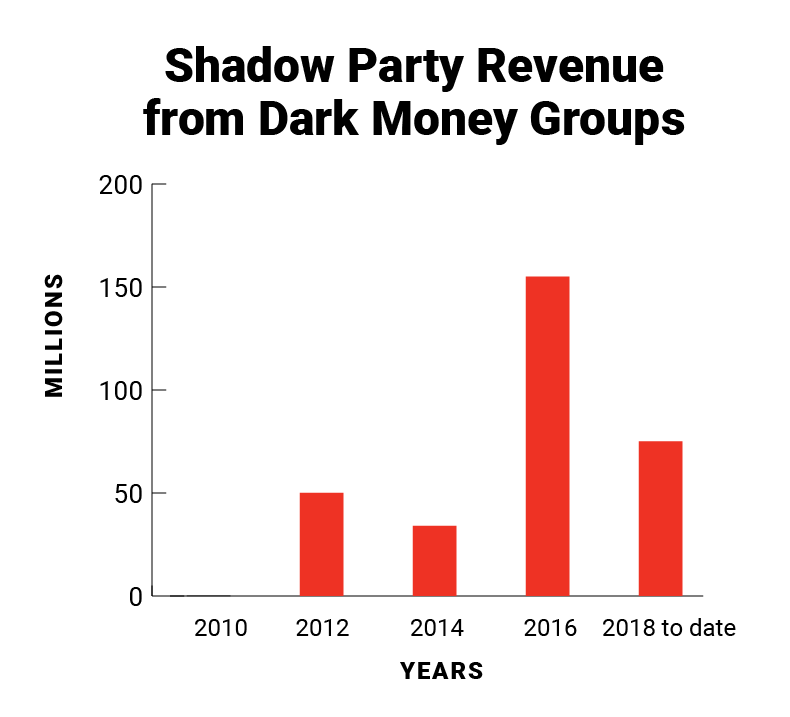

- In addition, the source of much of the shadow parties’ revenue is hidden from the public. Three of the Hill parties (the exception is House Democrats) make use of dark money groups that hide their donors and are run by the same people as their sister super PAC. Our estimate of dark money raised by shadow parties in the 2018 cycle is already more than twice the amount they raised for the last midterms. Official party committees can’t raise dark money.

- Shadow parties aren’t really independent. They are run by party leaders’ trusted former aides or hand-picked operatives. In many cases, party leaders personally make fundraising appeals for their affiliated shadow parties.

In other words, a system that relies more on shadow parties and less on official party committees further increases the already outsize influence of big money in elections and makes it harder for Americans to see who’s bankrolling political campaigns.

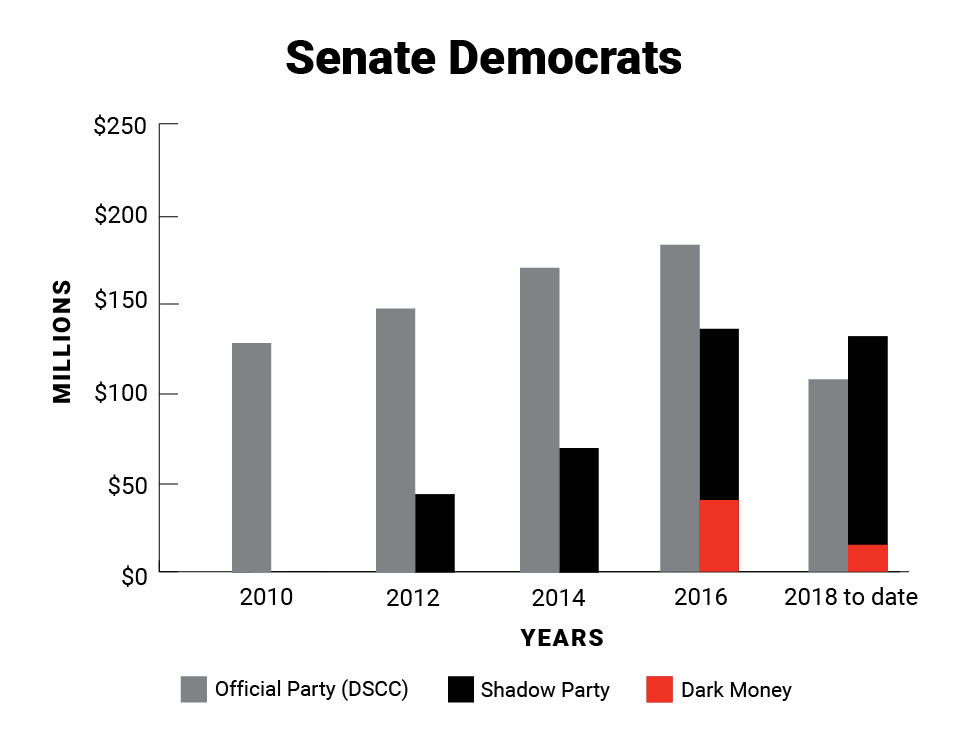

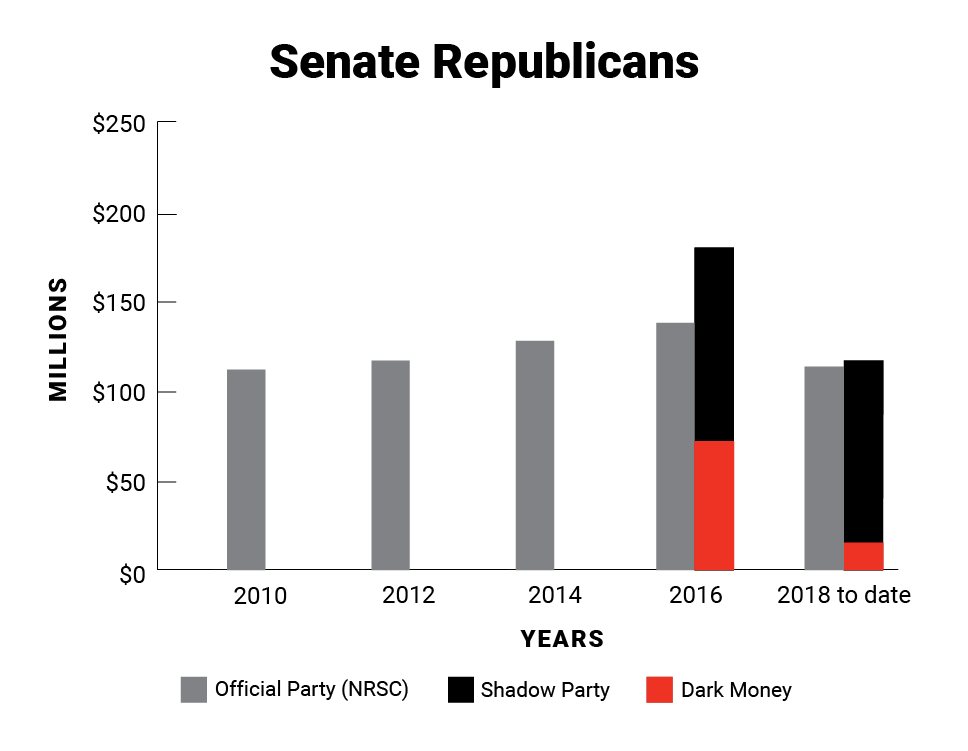

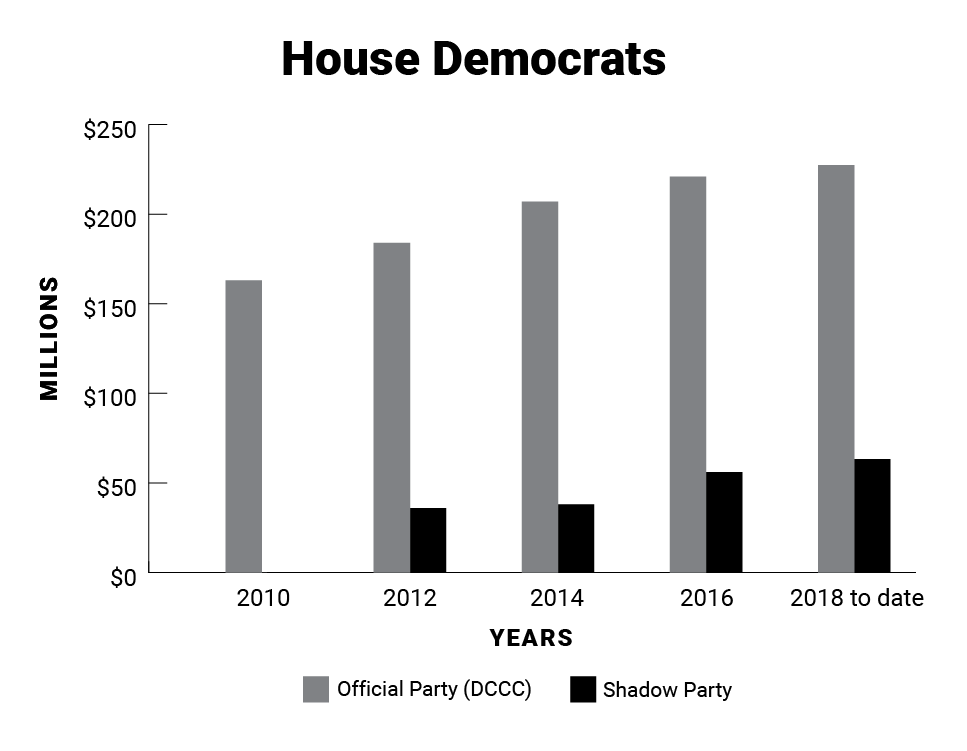

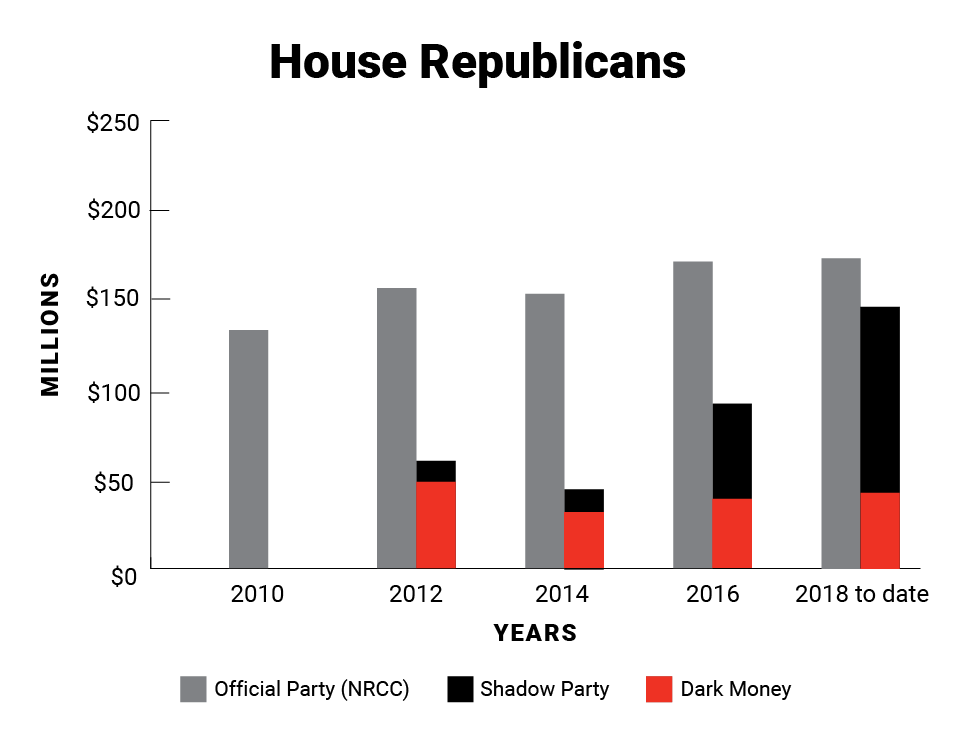

The following graphs show that so far in 2018, three of the four Hill committees are on track to see their fundraising rivaled or overshadowed by their outside-group affiliates. (The exception is the House Democrats, who continue to rely on massive fundraising by the official committee.) Senate Republicans’ shadow party groups already outraised the official committee last cycle. So far in 2018, both Republicans and Democrats in the Senate have seen the official party outraised by the shadow party groups.

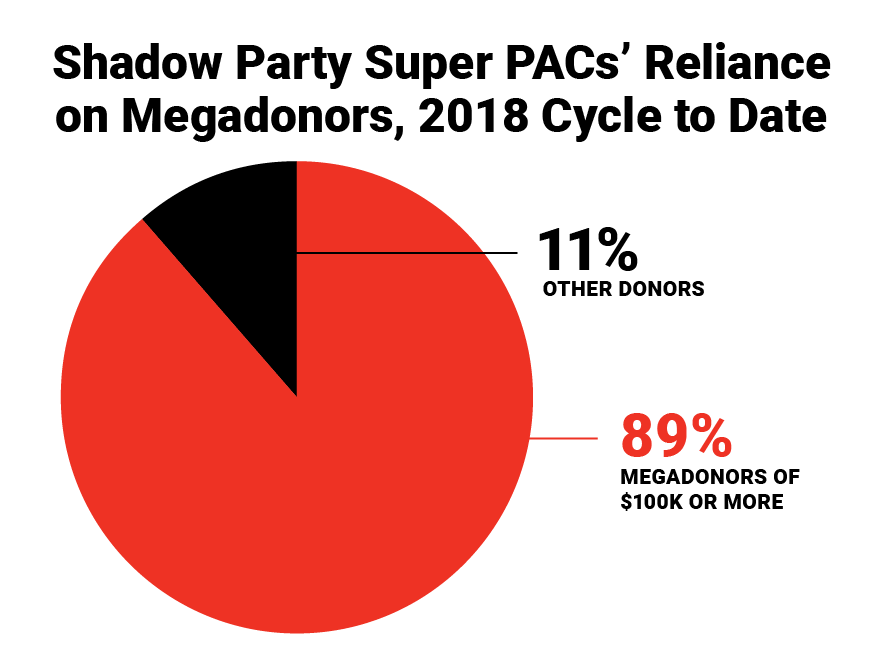

The following chart shows that money from megadonors of $100,000 or more makes up the overwhelming share — almost 90 percent — of shadow party super PACs’ fundraising. In fact, most of these groups’ money comes in amounts that would be illegal to give directly to a Hill committee. Donors are limited to giving $474,600 in the 2017–18 election cycle to a congressional party committee, yet across the four affiliated super PACs, donors exceeding that limit provided 73 percent of the money contributed. In addition, party committees are prohibited from accepting contributions from corporations and unions. But the shadow party groups take millions from these special interests.

The following graph shows that the parties are benefiting from tens of millions of dollars raised from donors unknown to the public. These amounts are difficult to estimate; the only source of information for the current cycle is the groups’ own statements (for past cycles, groups’ tax returns provide more information). Our estimate of the amount of dark money raised by shadow parties this cycle is likely too low; it’s based on groups’ announcements and press reports from recent months. Nevertheless, this cycle’s party-affiilated dark money total is already more than twice that of the last midterm election cycle.

Shadow Party Profiles

Shadow party groups spend exclusively on candidates from their party running for one or the other chamber of Congress. They are run by former top aides to the party leader or the official party committee, or were chosen to run the group by the party leader. Party leaders typically help them fundraise. They can share consultants or other strategic vendors with the official party or mimic the official party’s strategy based on publicly available information. Despite all this choreographing, shadow party groups maintain just enough formal independence to allow them to legally raise unlimited and often secret money.

Below, we profile the four super PACs and three dark money groups that operate as big-money arms of the congressional parties.

House Democrats

- House Majority PAC (super PAC)

Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi has long helped raise funds for the House Majority PAC. Virtually every staff member’s biography on the super PAC’s website lists prior work at the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. The group’s president is Alixandria Lapp, who used to be in charge of independent expenditures at the DCCC.

There is no dark money group affiliated with House Democrats’ leadership.

House Republicans

- Congressional Leadership Fund (super PAC)

The Congressional Leadership Fund’s founding president was Brian Walsh, who was previously the political director for the National Republican Congressional Committee. At the end of 2016, Corry Bliss took over the super PAC, reportedly at the insistence of Speaker Paul Ryan. The group’s treasurer, Caleb Crosby, is a former official with the National Republican Congressional Committee. Speaker Ryan and House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy have headlined fundraisers worth tens of millions for the group. Ryan was at an event where casino magnate Sheldon Adelson pledged $30 million to the Congressional Leadership Fund, and when the speaker decided not to seek re-election, Bliss thanked him for the “nearly $50 million” raised by the super PAC.

- American Action Network (dark money group)

American Action Network and the Congressional Leadership Fund are both run by Corry Bliss, and the groups share board members. AAN has spent exclusively in favor of House GOP candidates since 2012, and in the current election cycle alone it has given its sister super PAC over $20 million in dark money.

Senate Democrats

- SMP (formerly Senate Majority PAC) (super PAC)

SMP’s president is J.B. Poersch, former executive director of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee. The group employs former staff of Minority Leader Chuck Schumer. When Harry Reid was minority leader, SMP was run by former top Reid staffers. But when Schumer took the reins as minority leader in 2016, his former staff took over SMP. Reid reportedly raised money for SMP when he was minority leader. The super PAC has crafted ads based on material posted on Democratic Senate candidates’ websites.

- Majority Forward (dark money group)

Majority Forward is run by the same people as SMP, including its president J.B. Poersch, and the groups share office space. The two groups have the same spokesperson, who has described them as “allied organizations.”

Senate Republicans

- Senate Leadership Fund (super PAC)

The Senate Leadership Fund is headed by Steven Law, a former top aide to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. McConnell has reportedly encouraged top GOP donors to give to the super PAC.

- One Nation (dark money group)

One Nation and the Senate Leadership Fund are registered to the same address and both headed by Steven Law. Both groups also used to employ Ian Prior, a former secretary of the National Republican Congressional Committee. Majority Leader McConnell has reportedly directed Republican senators to “steer big donors to One Nation.”

Some charts have been edited since publication to more effectively allow for comparisons between charts.

(Image: BCJ/Shutterstock.com)