A public records lawsuit brought by the Brennan Center and Data for Black Lives revealed that the District of Columbia’s Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) collaborated with federal law enforcement agencies to surveil protestors in 2020 and 2021. We obtained over 700,000 pages of documents showing that the agencies shared information uncovered from social media platforms connected to racial justice protests on mass email chains, and they characterized protesters and activists as threats.

For years, the Brennan Center has raised concerns about the invasiveness and opacity of law enforcement’s surveillance of social media. These practices, which often target activists and marginalized communities, can inhibit individuals’ constitutional rights to free speech and protest. Absent credible public safety justifications, the sweeping, coordinated online surveillance of protests in the district raises serious concerns for the public’s First Amendment rights and underscores the need for stronger guardrails.

We obtained documents from February 2020 to January 2023 showing that the MPD compiled information largely collected from social media platforms about upcoming demonstrations and other public events, including the date, time, location, organizer, and estimated crowd size for each assembly. During racial justice protests in the summer of 2020, the MPD provided these lists to federal agencies, including the Secret Service, National Park Service, and the Department of Defense. Likewise, federal agencies disseminated similar lists to email threads that included over a dozen local, municipal, state, and federal government officials.

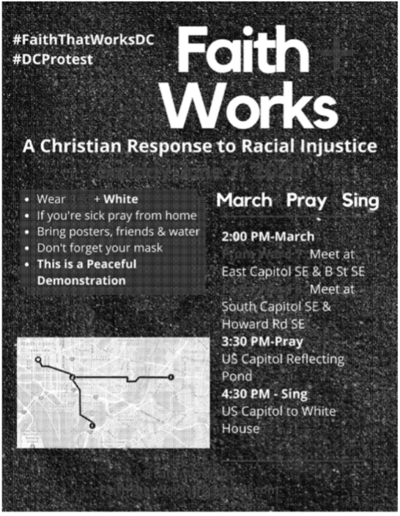

Other email chains contained screenshots of social media posts from organizations or individual organizers.

DC Metropolitan Police Department

DC Metropolitan Police Department

To gather this information, agencies noted who and what they should look out for on social media. In response to one email from an MPD lieutenant asking for accounts and posts from people on social media who were “urging people to riot,” one U.S. Capitol Police representative stated that they were tracking groups such as the DC chapters of Black Lives Matter, Refuse Fascism, and Showing Up for Racial Justice, along with terms including “Protest DC,” “Justice for George Floyd DC,” “BLM DC,” and “No Justice No Peace DC.” The Capitol Police official did not provide any evidence that these groups had “urg[ed] people to riot,” nor did the official demonstrate that the phrases they were tracking corresponded to credible threats to public safety.

Such broadscale monitoring of social media can blur the line between scrutiny of innocuous or constitutionally protected speech and monitoring for genuine public safety threats. Law enforcement surveillance of social media can also stifle groups, especially those from disfavored communities, from expressing their views or planning events online and may result in police intervention offline. During the summer of 2020, police departments across the country intensely monitored Black Lives Matter demonstrations and were disparately aggressive in their response to racial justice protests. This is in spite of the fact that the protests were overwhelmingly nonviolent.

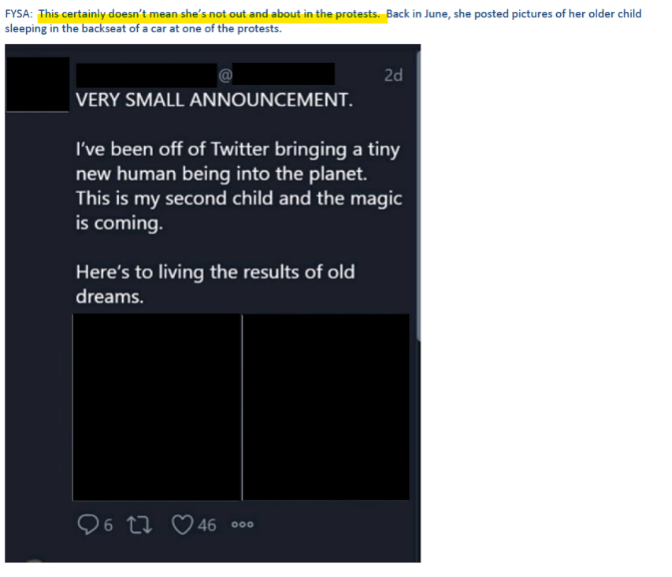

The risks of such social media monitoring are even more acute when police track individuals for their constitutionally protected activities. In one email, for example, a Capitol Police officer flagged a post in which a woman announced that she had given birth to her second child, noting that “this certainly doesn’t mean she’s not out and about in the protests” since she had “posted pictures of her older child sleeping in the backseat of a car” at another protest. The officer had previously described the woman as “one of the main Antifa organizers in DC.”

DC Metropolitan Police Department

DC Metropolitan Police Department

Other examples demonstrate how officers from the MPD and other law enforcement entities singled out individuals and groups who participated in or posted material on social media about racial justice protests for being affiliated with Antifa without evidence that they posed a threat to public safety. One Secret Service officer noted that one of the flagged groups, All Out DC, did not have “any posts inciting violence” on its social media. Instead, it appears these users were flagged for other law enforcement agencies because of the assumed threat they posed due to their beliefs and associations, increasing the potential they would be subjected to further surveillance or even unnecessary interactions with law enforcement.

Notably, the MPD officer who oversaw the department’s intelligence branch at the time and was heavily involved in these activities was suspended and subsequently indicted in part for allegedly providing Enrique Tarrio, the leader of the Proud Boys, with information about police investigations into the group. The officer’s connection to the Proud Boys only adds to concerns that bias rather than public safety was driving the department’s monitoring of racial justice protests.

Federal officials also disseminated false information about threats posed by protesters. Two reports from June 2020 — assembled by the Department of Transportation and the Naval Criminal Investigation Service and shared with the MPD and other law enforcement agencies — referenced “prestaging of bricks, rocks, sledge hammers [sic], . . . and other weapons at protest locations” within a section listing tactics, techniques, and procedures that the FBI’s National Joint Terrorism Task Force determined were used by racial justice protesters. Claims like these from the federal government, which were sourced from social media, had already been repeatedly debunked by reporting.

This information sharing about racial justice protests continued into 2021, with MPD and federal officials sharing social media posts about vigils marking Breonna Taylor’s murder, insinuating that other actors attending the vigils could commit acts of violence with no apparent evidence to substantiate that conclusion.

As it stands, the MPD and the federal government lack adequate policies to rein in online surveillance. The MPD’s policy governing the use of social media for official duties gives officers a wide berth to collect public information on social media without additional authorization, so long as it is for a “legitimate law enforcement purpose.” DC law is similarly permissive, allowing MPD officers to conduct “preliminary inquiries” of First Amendment–protected activities without prior authorization. Though the MPD is required to “safeguard the constitutional rights and liberties of all persons,” there are no apparent constraints to offset broad authorities, or mechanisms for guidance and oversight to ensure that officers’ monitoring of social media does not infringe on the public’s First Amendment rights.

The MPD’s monitoring of peaceful racial justice protests makes clear that additional guardrails are necessary to protect constitutional rights. The MPD should start by developing and implementing — with input from civil society and community members — a publicly available policy that includes concrete safeguards to rein in its officers’ monitoring of social media and internal measures to guide officers.

Reforming one police department, however, is not enough. The District of Columbia hosts dozens of law enforcement agencies, including 32 federal law enforcement agencies that assist the MPD. For example, the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security — both of which have permissive policies governing their use of social media — have a history of using social media to surveil protests, including those from the summer of 2020. To safeguard the public’s constitutional rights, comprehensive reforms to social media surveillance across all levels of government are needed.