It’s redistricting season, and legislatures are using new census data to redraw electoral maps. What we’ve seen so far isn’t pretty. Eighteen states have drawn districts already. Eight of them are heavily gerrymandered, in some cases even more aggressively than in 2010. Gerrymandering is hardly new. Both parties do it when they have a chance. But this year, there are new, disturbing twists that will make the gerrymandering more damaging and enduring than before.

As my colleague Michael Li notes, the surgical quality of the 2020 gerrymanders, aided by increasingly sophisticated data and mapping technology, will badly skew representation. In North Carolina, Republicans passed a congressional map that would eliminate 2 of 5 Democratic seats and that could give the GOP an 11 to 3 seat advantage in a strong GOP election cycle — all in a state with a narrowly divided electorate. New maps in Tennessee and Missouri could eliminate longtime Democratic seats in Nashville and Kansas City. In Illinois, Democrats passed a wildly contorted new congressional map that gives the party a 14 to 3 advantage in the state’s congressional delegation. New York could be next. In the game of rigging maps, though, Republicans have a stark advantage: Democrats control the drawing of just 75 districts compared to the 187 that Republicans control.

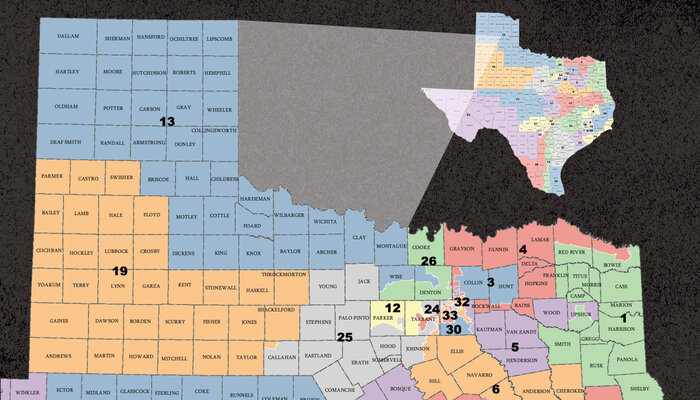

Speaking of Republicans, the legislatures they control are working to carve up suburban districts. These areas, once Republican strongholds, have purpled in recent election cycles. To counteract this trend, legislatures are cutting up the suburbs and joining them with overwhelmingly Republican rural districts.

In addition to the regional biases, it’s plain that the new maps target voters of color. Consider Texas. People of color accounted for nearly all of the state’s population growth, but the redrawn Texas map will deliver precisely zero new opportunities for minority representation in Congress. In fact, the Texas Legislature may even have found a way to reduce Latino voting power by shifting a significant block of them into an overwhelmingly conservative rural district.

The Supreme Court created a legal loophole that opens the door to these racially motivated gerrymanders. While racial gerrymandering is illegal, the 2019 Rucho decision announced that courts can’t police partisan gerrymandering. So political operatives simply say that blatantly racial — even racist — map drawing is just good old partisan politics. (We’ll be fighting to make sure they can’t get away with that.)

The Texas map represents another disturbing trend: a dramatic decrease in competitive seats. Even in a Democratic “blue wave” election, only one congressional seat currently held by a Republican would be competitive in the Lone Star State. (The 2010 map contained as many as six competitive seats.) Indeed, Democrats would have to win an absurd 60 percent of the statewide vote to capture an additional seat in Congress.

A democracy in which huge swings in voter preference produce marginal changes in representation, in which entire communities are targeted and disempowered with no legal protection, is an unhealthy democracy.

Only Congress has the power to fix this mess. The Freedom to Vote Act and the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, currently pending in the Senate, would ensure fair representation for all Americans. All we need is 50 senators and a little bit of political courage.