Losing Our Punitive Civic Religion

Much of the American legal system is based on a set of enduring myths about who are criminals and how they should be treated.

Part of

This essay is part of the Brennan Center’s series examining the punitive excess that has come to define America’s criminal legal system.

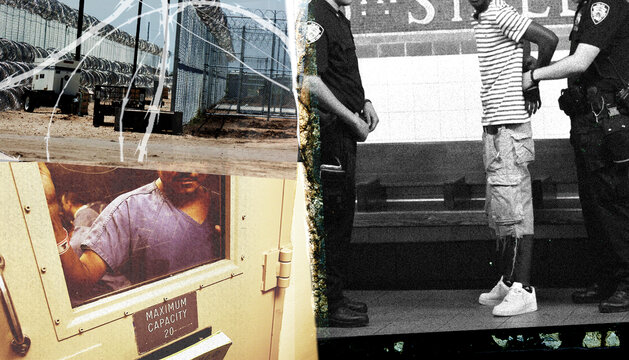

Like the Covid-19 dead, the mass suffering and racial disproportionality of our highly punitive criminal justice system — police, prisons, court supervision, immigration detention — sit heavily on American society today. With prisons second only to long-term care facilities in rates of Covid-19 deaths, we might do well to recognize that they bear the very same burden in some important ways. In both transmissions and punishments, the United States has become infamous globally as the country with a single digit share (5 percent) of the world’s population, and as of February a double-digit share (20–25 percent) of both Covid-19 cases and prisoners.

Accelerated by the parallels between these crises, the United States is experiencing a remarkable wave of interest in reforming our criminal justice system. Serious attention is even being given to the argument that it is past time to abolish (or at least “defund”) such long-standing criminal justice institutions as police and prisons. But neither reform nor abolition will get very far unless we undertake a substantial rethinking of what we want and expect from criminal law and punishment. Centuries of enthusiastic innovation in both (always in the name of reform, and often with abolition of some crueler penalties in mind) have instead left us not with meaningful change, but with a set of powerful punitive myths that have become a genuine American civil religion — one that offers criminal accountability as a kind of sacrament of legal fidelity, and state punishment as a primary source of individual correction and social improvement.

These beliefs have enjoyed extraordinary popularity in our history, helping to make criminal law one of the primary subjects of both popular entertainment and electoral politics, and rendering criminology a form of popular science. To call them myths is contentious, but it is our very lack of interest in testing them empirically that sustains support for everything from library fines to the death penalty. Left largely unchallenged in courts, legislatures, pulpits, newspapers, and universities, these myths make it exceedingly easy for Americans collectively to address criminal law and punishment, when what we require instead is the more demanding work of reforming our democracy and reinventing our forms of social solidarity.

Perhaps the oldest myth in our punitive civic faith, one with roots in medieval theology, has the high-minded label “accountability.” People who commit crimes have to be held accountable; their debt to society must be paid. Left unsaid is why crimes, which generally are complex social events with many causes, should be thought of as creating a “debt,” and why punishment should be seen as a “repayment.” The appeal of accountability, of paying your debt to society, is supposed to be requalification and reintegration; in reality, it has usually meant the opposite.

The United States is hardly alone in emphasizing accountability as a principle. It can be found in the penal law of all nations and also in modern human rights law, which is particularly insistent that crimes against humanity not be forgiven, even as part of reconciliation in conflict-ridden societies. But America is unique in the degree of our zeal for full payment. We allow thousands to die in prison. We pursue even those who eventually win release with demands for financial repayment of the cost of their punishment. Letting people go without paying their full debt is treated as an anathema on both sides of our political divide, even though many experts agree it will be essential if we are to clear our chronically overcrowded prisons, which were sites of medical suffering even before Covid-19.

Myth two divides the population into the hardworking and the idle, attributing crime to the latter. This myth dates back to the post-revolutionary period, when the disruption of the war, economic transformation, and increased immigration led to the first of many political turns toward criminal law as a means to improve the social order of the new democracy and its concomitant slave society.

The birth of the penitentiary in the Northeast in the early 1800s as a place of forced labor and solitary confinement was perhaps the most famous and influential response. A less visible form of the merger of forced labor and containment was slavery and especially the carceral form of plantation slavery in the Mississippi Delta during the cotton boom. The prison and the plantation were supplemented by forms of organized policing, namely the slave patrol in the South and the “London” model of uniformed municipal police, organized along semi-militarized lines. In both cases idled workers were effectively criminalized (e.g., unaccompanied enslaved persons were prosecuted and imprisoned as “vagrants”).

Today, the almost religious zeal with which 19th century reformers once touted the curative value of forcing the idle to work has slackened somewhat, but in other ways it lingers, especially for the poor. Our prisons still make people work without rights or minimum wage compensation but without imparting meaningful skills that could open employment opportunities on reentry. And young people out of work or school are still the most likely targets of policing and prosecution. In a society that seems to have less paid work for many, this is a formula for more punishment, not less.

Perhaps the most punitive myth of all, one that has been a recurrent source of criminalization and extreme punishment, is only about a century old: the belief that our law enforcement institutions — judges, police, prosecutors, prison officials — are expert at identifying the truly dangerous, whose removal to prison would make society much safer.

This article of civic faith is rooted in the astounding success of the racist pseudoscience of eugenics. The early 20th century movement among eugenicists to control reproduction and immigration and to increase law-enforcement powers promised that crime could virtually be eliminated by removing or incarcerating (or even sterilizing) those with genetically based “criminal traits.” The primary targets were immigrants from eastern and southern Europe, African Americans, and rural whites, all of whom were presumed to be criminally inclined based on heredity and race.

It was after immigration was effectively cut off in 1924 that eugenic theory made Black communities the central focus of punitive enforcement. The scandals associated with sterilization in the United States and eliminationist practices toward the disabled in Nazi Germany ultimately discredited eugenics as science.

But the belief that most serious crime was caused by a dangerous and deviant minority survived. While the search for causes slipped from biology to sociology, the reliance on criminal records guaranteed that the eugenic era’s racialized thinking about crime would continue. Today we are increasingly likely to rely on statistical indicators driven by algorithms to identify the dangerous, but advancing technology erases rather than removes the racist legacies of this approach. We continue to believe that the people we currently jail after arrest, or those we imprison after conviction, were properly selected for their dangerousness. This belief makes serious efforts to end pretrial detention or prolonged imprisonment a bridge too far for contemporary politicians.

By the 1970s, all of these myths were losing their cultural credibility, demonstrated in serious discussions of reducing reliance on imprisonment and reconceiving the concept of public safety. By the end of the decade, however, a new campaign to address social instability through more policing and imprisonment was ascending. A new myth — that cleansing neighborhoods of likely offenders (“Broken Windows”) would save them from a tide of violence and poverty — helped justify the largest increase in prisons and policing in our history.

Our punitive past, however, need not doom us to a punitive future. The ideas that have become our civic faith need to be reinvented in light of our evolving commitment to decency and subjected to the kind of experimentation and testing we demand from other aspects of government. Can accountability be honored in ways other than punishment? Can dignity and security be afforded to people by means other than wage labor? Can risk factors that increase the chances of people becoming involved in criminal conduct be recognized and redressed without labelling the people exposed as “dangerous”? Can the government promote neighborhood efficacy and morale without hounding the unhoused and hungry from our streets and parks? These are questions that are too often treated as if we already knew the answer were “no” — a faith that’s past time to lose.

Jonathan Simon is the Lance Robbins Professor of Criminal Justice Law at UC Berkeley.

More from the Punitive Excess series

-

Crime, the Myth

It’s up to society to say what is and isn’t a crime, and it varies more than one might think. -

Race, Mass Incarceration, and the Disastrous War on Drugs

Unravelling decades of racially biased anti-drug policies is a monumental project. -

The American ‘Punisher’s Brain’

U.S. sentencing practices seem especially extreme when compared with countries like Canada, Germany, and the Netherlands.