The closely-watched Republican Senate primary in Mississippi – seen by many as a proxy for the larger battle between Tea Party and establishment forces within the Republican Party – will finally come to a close tomorrow. Six-term incumbent Senator Thad Cochran will face Tea Party-supported Chris McDaniel in a runoff election required because neither gained a majority in the June 3 primary. After the defeat of House Majority Leader Eric Cantor seemed to breathe new life into the Tea Party, money has poured into the already-expensive Mississippi primary. A Brennan Center analysis of independent spending in the race reveals several notable characteristics:

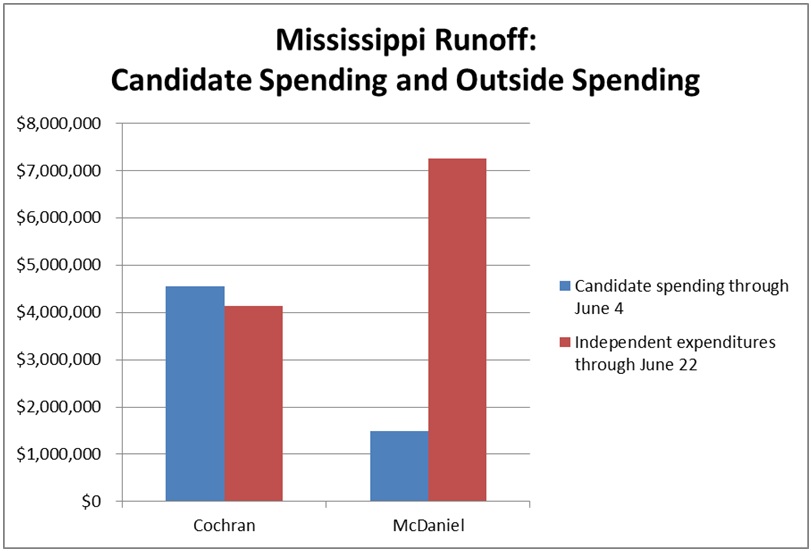

- The contest is another example of an establishment Republican receiving more in direct contributions than a Tea Party favorite, this time by $3 million, while outside spending runs significantly in favor of the Tea Partier, by $3.1 million.

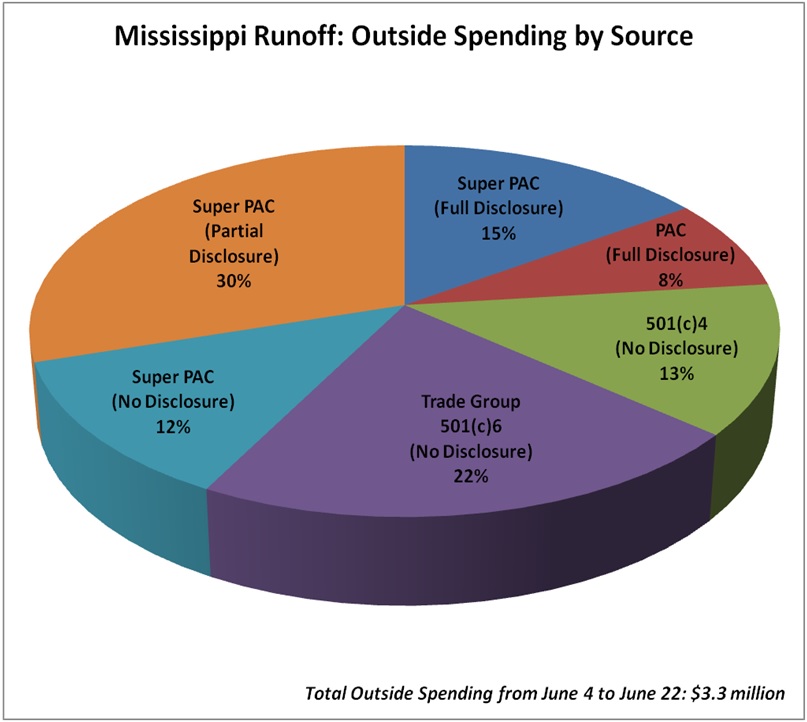

- Outside spending had exceeded candidate spending by more than $2 million as of the primary election on June 4. In the less than three weeks since the runoff began, there has been $3.3 million in outside spending.

- During the runoff, 77 percent of outside spending came from dark money groups that do not fully disclose their donors.

- Candidate-specific super PACs have allowed “double-dipping” donors to give more money in support of their champion than candidate contribution limits would allow.

- The biggest pro-Cochran spender is a single-candidate super PAC that has spent $1.8 million and accepted five- and six-figure donations from maxed-out Cochran contributors.

Independent spending

Outside spending in the race totaled $11.4 million dollars as of June 22. In the runoff alone, which began June 4, outside expenditures hit $3.3 million. By way of comparison, the candidates together spent $6 million for the pre-runoff portion of the primary.

Spending in the race is following the pattern observed in prior Brennan Center analyses of struggles between Tea Party and establishment Republicans. The establishment candidate has a solid fundraising advantage: incumbent Cochran raised $3 million more than Tea Partier McDaniel as of June 4. But there’s more outside money on the insurgent’s side: through June 22, independent expenditures favoring McDaniel are $3.1 million higher than those favoring Cochran. Almost three-quarters of the pro-McDaniel outside money came from just three national conservative super PACs: Club for Growth, Senate Conservatives Action, and Tea Party Patriots Citizens Fund.

Dark money

The majority of outside spending in the primary has come from dark money groups. Organizations that do not disclose or only partially disclose their donors were responsible for 56 percent of spending in the primary through June 22. And during the runoff, 77 percent of outside spending has been dark money.

Club for Growth Action, which accepts money from groups that don’t disclose their donors, is by far the biggest spender in the race. It has doled out $3.1 million in favor of McDaniel. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, a nonprofit trade group that doesn’t disclose its donors, spent $1.2 million in support of Cochran, in addition to giving $100,000 to a pro-Cochran super PAC. The National Association of Realtors Congressional Fund, a super PAC that receives all of its money from an affiliated nonprofit that doesn’t reveal its donors, put up $781,000 in Cochran’s favor.

Single candidate super PACs and double-dipping donors

Both candidates have single-candidate super PACs in their corner, although Cochran’s has been far more active. These PACs allow donors to “double dip” by giving the maximum allowed to the candidate – $2,600 for the primary – as well as many times more to a super PAC devoted to electing that candidate. Super PACs can also accept money from corporations and unions, which are prohibited from making candidate contributions altogether.

A super PAC called Mississippi Conservatives has spent $1.8 million supporting Cochran and attacking McDaniel. The group has been a prolific fundraiser, and its receipts include large donations from several people who maxed out in their direct contributions to Cochran. For example, Joe Sanderson, the Cochran campaign’s finance chairman, contributed the maximum amount to Cochran’s primary campaign and gave $200,000 to the super PAC. Haley Barbour, former Mississippi Governor and current head of a major lobbying firm, has been a strong supporter of Cochran and has given up to the cap for Cochran’s primary and general campaigns as well as $10,000 to Mississippi Conservatives.

A pro-McDaniel super PAC, Revive America, has raised money from a handful of individuals who gave the maximum to McDaniel’s campaign. But with only $5,300 in expenditures, it presents no real competition for the pro-Cochran Mississippi Conservatives.

Candidate fundraising

Analysis by the Center for Responsive Politics of the candidates’ fundraising prior to the runoff shows stark differences between the two. Cochran was far ahead in fundraising, with $4.5 million compared to McDaniel’s $1.5 million. He relied heavily on PAC contributions, at 42% of his haul, and hardly at all on small contributions from individuals. Incumbents often receive more PAC donations, since PACs largely represent special interests and other politicians.

McDaniel, on the other hand, raised 35% from small contributions and very little from PACs. Many of McDaniel’s contributors are not Mississippians: 73% of his war chest came from out of state, compared to only 23% of Cochran’s. McDaniel’s success with out-of-state donors is likely due in part to the efforts of the national groups Club for Growth and Senate Conservatives Fund, both of which have bundled contributions for him in addition to making hefty independent expenditures.

Cochran’s longtime membership on the Senate Appropriations Committee has been an issue in the campaign. He has faced attacks from the right accusing him of contributing to high federal spending and bailouts. At the same time, the benefits of being a senior member of a top-tier committee are clear: his ability to steer funding has earned him friends in the lobbying industry, which has made half a million dollars in contributions to his primary and runoff campaigns.

Cochran’s allies in the Senate have come to his aid. The National Republican Senatorial Committee held a fundraiser for him on June 10 that raised $820,000, and his runoff campaign had received over $100,000 from other Senators’ leadership committees through June 13.

It remains to be seen whether transfers from leadership and joint fundraising committees come to play a larger role in tight primaries like this one following the Supreme Court’s McCutcheon decision, which struck down aggregate giving caps that limited the amount these committees can collect in a single check. After the McCutcheon ruling, Cochran joined with 18 other Republicans to form the 2014 Senators Classic Committee. Before McCutcheon, donors had been limited to giving $48,600 per election cycle to all federal candidates. Now, the Senators Classic Committee is structured so that a single donor can give $98,800, which would be distributed amongst the members. According to the FEC website, however, the committee has yet to receive any money.

* * *

The last-minute surge of outside spending in this race has illustrated some of the disturbing realities of the post-Citizens United world. Inadequate disclosure leaves the voters in the dark about who is trying to influence their votes and curry favor with the candidates. And candidate-specific super PACs make a mockery of contribution limits. The Supreme Court must recognize these problems and reverse course. And lawmakers must examine new opportunities to limit the flood of dark money into elections. If we are to have a fair and functioning democracy, we must ensure the public can know who is funding political campaigns.

(Photo: Flickr/Jenni Konrad)