The power of the prosecutor is tremendous, impacting the life and liberty of those whose conduct brings them within the criminal justice system. Prosecutors decide who gets charged and what crimes they get charged with. They make influential recommendations about sentencing. That’s why it’s essential for prosecution to stay independent of politics. Justice demands that prosecutors make decisions based solely on the facts and the law, and without fear or favor. No one can be above the law or unfairly subjected to it.

New federal prosecutors learn about former attorney general and Supreme Court justice Robert Jackson’s views, which, although stated in 1940, resonate powerfully today:

[The prosecutor’s] discretion is tremendous. He can have citizens investigated and, if he is that kind of person, he can have this done to the tune of public statements and veiled or unveiled intimations. . . . The prosecutor can order arrests, present cases to the grand jury in secret session, and on the basis of his one-sided presentation of the facts, can cause the citizen to be indicted and held for trial. . . . While the prosecutor at his best is one of the most beneficent forces in our society, when he acts from malice or other base motives, he is one of the worst.

There were echoes of Jackson’s warning last week when the Justice Department indicted one of the president’s political opponents. Lindsey Halligan, President Trump’s former personal lawyer and newly installed U.S. attorney in the Eastern District of Virginia, went to the grand jury, apparently alone, to indict former FBI Director James Comey for allegedly lying to Congress and obstructing a congressional investigation.

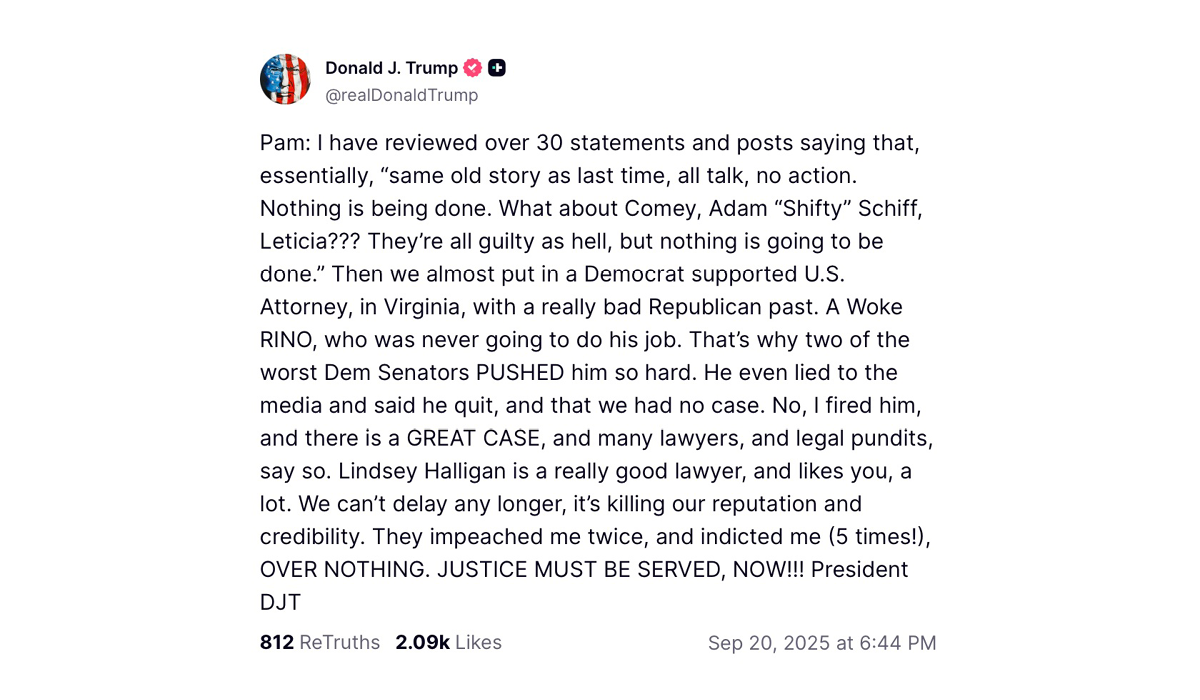

Trump turned to Halligan after her predecessor — Erik Siebert, an experienced career prosecutor whom Trump himself had tapped to lead the office — declined to prosecute Comey due to insufficient evidence. Grand jury secrecy means we don’t know the precise rationale, but there is credible reporting that prosecutors in the office had serious concerns about the case. That prompted Trump to put out a Truth Social post that read more like a text message to Attorney General Pam Bondi than something you would expect to see from the president on social media.

This level of presidential interference in prosecutorial decision-making contradicts everything our country has done in the post-Watergate era to protect against corruption in the justice system. This isn’t the first time Trump has interfered with the DOJ’s independence — his administration fired FBI agents and prosecutors for working on cases Trump disapproved of, and the interim U.S. attorney in the Southern District of New York resigned in lieu of obeying an order to dismiss the office’s public corruption case against New York Mayor Eric Adams — but it is the most egregious. The administration replaced Siebert with a lawyer with no prosecutorial experience and no basis for overruling her predecessor’s assessment of the case. The administration directly intervened to indict one of the president’s personal enemies after he openly called for it — demanded it, even. This is as far as it is possible to be from an indictment based on the facts and the law.

Halligan may have obtained the indictment the president wanted, but it reflects the flawed process that produced it. Grand jurors rejected one count in the proposed indictment, reportedly involving an additional false statement, which happens very rarely. It’s not a good sign for the strength of the government’s evidence. It’s one thing to get a grand jury to indict. Getting a conviction is an entirely different matter.

Comey is charged with lying during a 2020 Senate oversight hearing. But the dispute is primarily over testimony he gave to a Senate committee in 2017, in which he denied authorizing any FBI employee to be an “anonymous source” to the media. That testimony is outside of the five-year statute of limitations, and the government could not bring charges based on it. So prosecutors are instead using Comey’s 2020 testimony, in which he reaffirmed his earlier answers in a colloquy with Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX).

Cruz repeatedly mentioned Comey’s number two at the time, Andy McCabe, and a dispute over statements McCabe made to the press about the 2016 presidential election. Comey had testified that he didn’t “authorize” McCabe to make those statements, and McCabe said publicly that he had advised Comey about them after the fact. Once the indictment was made public, most people assumed that this was the supposed lie with which Comey was charged.

But the indictment offered only a vague description of the circumstances surrounding Comey’s conduct, alleging that Comey “authorized someone else at the FBI to be an anonymous source in news reports.” Subsequent reporting speculated that the indictment actually refers to one of Comey’s friends, Columbia Law Professor Daniel Richman, who provided some of Comey’s memos to the press shortly after Trump fired Comey in 2017. The release of that information led to the appointment of Robert Mueller as a special counsel to investigate Russian election interference and potential connections to the 2016 Trump campaign.

In other words, the indictment isn’t particularly clear; it’s possible for informed people to entirely misinterpret the testimony to which it refers. Nor can Comey, as the defendant, discern what conduct he is being charged for simply by reading the indictment. The government fails to specify what lie Comey supposedly told or what evidence it has to suggest that he knew any portion of his 2020 testimony was false. Even the government’s best case, if the indictment were about McCabe, wouldn’t establish “authorization,” which means approval in advance. And presumably, Comey is skillful enough that if he’d wanted Richman to provide information to the press, he wouldn’t have “authorized” it. The term “anonymous source” is also subject to interpretation. There are big enough holes in the indictment for a skillful defense lawyer to drive a truck through.

Our criminal justice system does not permit trial by surprise. The Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure require that an “indictment or information must be a plain, concise, and definite written statement of the essential facts constituting the offense charged.” An indictment that isn’t clear on its face could be legally insufficient. Defense lawyers might move to dismiss the case or at least ask the judge for a “bill of particulars,” which would require the government to disclose more details about its particulars. But here, the failures in the indictment also point to a substantive difficulty the government will face if the case goes before a jury. It’s not at all clear that Comey knowingly lied — which the government must offer compelling evidence for in order to win a conviction.

When Cruz questioned Comey, it wasn’t in the role of a skillful prosecutor trying to box in a witness. It was part of a Senate hearing designed to score political points. The questions were imprecise, and Comey didn’t ask for clarification; he simply reaffirmed his 2017 testimony that he had not “authorized” anyone to act as an “anonymous source.” It would be an awfully heavy lift for the government to convince trial jurors, beyond a reasonable doubt, that Comey understood he was being questioned about Richman, whom Cruz never mentioned, in the midst of repeated invocations of McCabe’s name.

The second count in the indictment isn’t crafted with any greater skill. It alleges that Comey “did corruptly endeavor to influence, obstruct and impede the due and proper exercise of the power of inquiry under which an investigation was being had before the Senate Judiciary Committee by making false and misleading statements.” Note the reference to statements in the plural, even though the first count of the indictment references only one allegedly false statement. And again, it’s not clear what statements are implicated. Nor is it clear what evidence the government has to suggest that Comey had a “corrupt” state of mind and an intent to interfere with the committee’s work, as prosecutors would need to prove to convict on this count.

All told, the indictment doesn’t look like the work of experienced prosecutors who understand the scrutiny to which any indictment, and certainly this one, will be subjected. Federal prosecutors use a robust review process to surface issues in an indictment before they take it to a grand jury. That doesn’t seem to have happened with this one.

There is plenty to question about the process that led to this indictment, along with its substance, starting with the unusual replacement of the U.S. Attorney in the Eastern District to obtain it. It was a rushed affair — not surprising given that the statute of limitations was about to run out on even Comey’s 2020 testimony. The magistrate judge who accepted the return of the indictment noted that the grand jury hadn’t ever convened as late in the day as the one that indicted Comey did, getting to work at 6:47 p.m.

A grand jury need only find that there is probable cause to return an indictment. That means jurors must have a reasonable belief that a crime was committed and that the defendant was the person responsible. In Comey’s case, even the grand jury vote on that low burden of proof was close. Federal grand juries consist of 23 grand jurors. It takes 12 votes to obtain an indictment. We don’t know how many grand jurors were present during the session when Comey was indicted. But only 14 of them voted in favor of indicting on the two counts on which they returned charges, and there was reportedly an additional count they refused to indict on.

Such a slender margin is unusual. Even though they are not required to, grand juries frequently act with unanimity or something close to it. The absence of consensus does not bode well for prosecutors who must establish guilt beyond a reasonable doubt — a much higher standard than what is required to indict — by a unanimous jury vote at trial. In the grand jury, the defense has no opportunity to tell its side of the story. At trial, the defense’s legal team will have the opportunity to poke holes in the government’s case and present evidence and argument on their client’s behalf.

The question now is: Will there be a trial, and how quickly will it happen? After news of the indictment became public, Comey said he wanted one. He seemed serious about that. But electing to go to trial could mean waiving certain legal defenses that must be made ahead of trial, and it’s unlikely that his skilled legal team, which includes former U.S. attorney Patrick Fitzgerald, would be enthusiastic about that approach.

Comey’s team could try to get the case dismissed by arguing that he’s a victim of selective prosecution (he’s been singled out for charges because of Trump’s dislike of him) or vindictive prosecution (he’s being prosecuted in retaliation for exercising legal rights, like the First Amendment). These arguments rarely succeed. But if ever they would be successful, this would be the case, given Trump’s statements both before and after his public “direction” to the attorney general to get it done.

If this case does go to a trial jury, the government’s burden of proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt will loom large. The prosecution bears the burden of proving every element of a crime beyond a reasonable doubt to the satisfaction of every member of the trial jury in order to convict. If the jury finds it’s as likely that the defendant didn’t do what he’s accused of as it is that he did, that must result in an acquittal. The government would not get a second chance because of the Fifth Amendment’s protection against double jeopardy, which prevents it from prosecuting someone twice for the same crime.

The government doesn’t have a clear path forward here, and that’s very likely why experienced prosecutors in the Eastern District of Virginia weighed in against indicting. The Federal Principles of Prosecution obligate prosecutors to only indict if they believe a target’s conduct constitutes a federal crime on which prosecutors can obtain and sustain a conviction with the admissible evidence available to them. So prosecutors must look beyond the technical low bar to obtain an indictment.

It’s unclear what Halligan, just days into the job and lacking prosecutorial experience, knows about the Federal Principles of Prosecution. She certainly didn’t heed them. If nothing else, Justice Jackson’s advice to prosecutors should have served as a guidepost: “The citizen’s safety lies in the prosecutor who tempers zeal with human kindness, who seeks truth and not victims, who serves the law and not factional purposes.” But it didn’t. We are left with a prosecution that is undeniably tainted with politics, and that’s not justice.