This was originally published by The National Book Review.

This was originally published by The National Book Review.

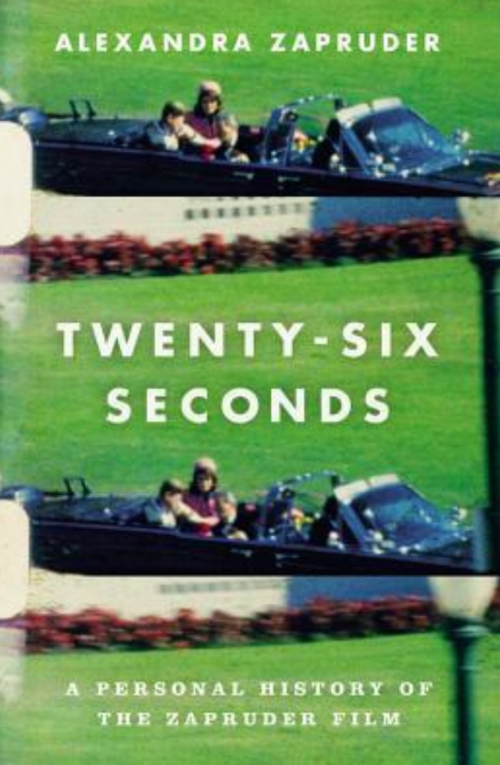

Alexandra Zapruder is the granddaughter of Abraham Zapruder, who filmed the iconic twenty-six seconds of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas on November 22, 1963 on his brand new Bell and Howell 414 PD Director Series 8 mm motion picture camera. In Twenty-Six Seconds, Zapruder traces the story of the world’s most famous home movie from its recording in Dallas to its temporary home at LIFE Magazine to the National Archives in Washington, DC, and all the people the movie touched along the way. An entrancing story, the book captures the moral dilemmas and heart-wrenching decisions that affected three generations of the Zapruder family as they dealt with the film’s legacy. Despite dozens of scholars and researchers covering the topic before, Zapruder’s book tells the behind-the-scenes story not only of the film’s place in American history, but of what it means to be an accidental guardian of America’s memory.

Before the paperback release of the book, Zapruder spoke to Lauren-Brooke Eisen for The National about writing this story about a film that meant so much not just to the American people but also to her family.

Q: The “Zapruder film” is such an iconic part of American history. Obviously, it is the only film record of critical aspects of a momentous event. But what else is it about the film that has caused it to leave such a deep impression on the national psyche?

A: There are other films of the assassination and a large photographic record of it. But my grandfather was standing at exactly the right vantage point to capture the entire series of events. This film is more complete than the others. It’s a story, a narrative – the president and first lady as themselves and then you see the entire thing unfold. I think it took hold partly because it created a national memory of an event that was deeply traumatic in the country. It gave people a way of seeing something that was terribly important and affected them individually.

It was also the first of its kind in the sense that up until this time there had not been a visual record of something quite so violent and so important. It became a subject of enormous debate about what the public has a right to see and own. Had the film been less graphic and disturbing, there might not have been such a fight over it. Interestingly, there were forces that thought it should not be seen so publicly because of its violent nature. On the other side, there were researchers who thought that it would provide information on what happened to the president.

Ultimately, it occupied this place in a larger cultural dialogue about what is visual truth. The film showed what happened to the president without answering the question about how it happened to him. There were artists and researchers who came back to it over and over as a touchstone of visual information. It speaks to the difference between information and truth.

The moral dilemmas were also very compelling. All the players are reasonable people. There are no villains. People just had deeply different ideas about what should be done.

Q: Were other films taken of Kennedy’s assassination?

A: There is another film that was taken across the street. You don’t see the impact of the bullets as clearly but you do see Jackie on the back of the car. There is a series of still photographs and a smattering of photographs here and there. They have been put together with the film and the other evidence to increase the perspective and amplify the information but they don’t provide the entire story.

Despite the fact that my grandfather was an amateur, he was a pretty good filmmaker and had a good camera. It was set to full zoom and he maintained his composure the entire time. A lot of things came together to create something that would stand the test of time.

Q: You write in the introduction that it was difficult to write this book because your family shunned attention about the film. What did your family think when you told them you wanted to start this project? How has the book been received by your family?

A: I would say that there were mixed feelings inside my family. Some family members immediately understood what I was trying to do and why I would be compelled to do this. Others were more resistant to it partly because of the ethos in the family of not calling attention to the film and not wanting to be perceived as disrespectful to the Kennedy family. My own grandfather and father did not like to talk about it. But over time and certainly after the book came out, even the members of my family who were not so sure about it came to see the value in this endeavor.

I realized through this process that what was missing in our family was the intrinsic curiosity about the film. For us, it was this thing we had to deal with. I was the first one to come along and say this is an amazing story, and it was not until I wrote the story that those who were against it could see it. I was trying to create a narrative for our own family and the general public. At first, I was resistant to embrace my own voice and words. My first attempts at a proposal were a failure. I realized that anyone could write a narrative nonfiction book about the Zapruder film – and that had been done – but once I realized why it was important for me to write it, I made my peace with it and the rest inevitably followed.

I also think it took distance. It took 50 years. I don’t think my father would have been able to see it this way. It was too personal. He was too involved with its legacy. Had it not been a home movie, these issues would not have played out the way they did. Because my grandfather was an individual person there is this tension between the public and the private. If my grandfather was an AP reporter, this story would not have been as interesting.

Q: One of the themes of this book certainly seems to be (as you have written) that your grandfather was stricken with severe grief over JFK’s assassination, revulsion at the violence captured by the film that he took, a deep discomfort with profiting off the film, and uncertainty about what to do with it. Is this something you knew at the outset of your research, or did you uncover these truths as you started to research and write this book?

A: I knew on some level that it was a source of tremendous pain for my grandfather and the family. I knew from the very beginning that the most compelling reason not to write this book was the moral dilemma about the film’s use and sale. There was shame and ambivalence and this was the painful undercurrent that I would have to come to terms with. I think at the end of the day I felt a profound conviction in my grandfather and father’s humanity. Even though they may not have made all the right decisions, I knew they approached the decisions with decency, thought, and a strong moral compass. Being able to convey that without being defensive was something I worried about.

Part of it was wanting to be the one who confronted it and in the most personal sense eventually answer the questions of my children and nephews and not pass on that doubt and silence and uncertainty. I realized that the story is complicated but it is not shameful.

Q: You grew up with a very distinctive name that is inextricably tied to the Kennedy assassination and your grandfather’s film. What was it like growing up as a “Zapruder,” and how have people reacted to it—and what have they asked you—over the course of your life?

A: I understood my identity as a Zapruder the way it was constructed by my family – being a Zapruder meant being a Washingtonian, a Democrat, a Jewish person; that is how I understood my identify most of my life. In my 20s, if someone asked me to name the top 5 most interesting things about me, I would not have mentioned the film. In the 1990s, our name was frequently in the newspaper, and I became more aware that it was associated with the Kennedy assassination. But it was not until I wrote the book that I assimilated that part of my identity and what it means to wear the name Zapruder. It is a twist of fate that it’s such a strange and unique name.

When people ask about the name and inquire whether I am related to that guy who took the film, I am always surprised. When I was younger, I felt vulnerable about it because of how my parents and grandparents felt, I knew people carried an assumption about my family. It was a conflict for me as I knew who we were and it didn’t tally with how we were sometimes characterized – greedy or money-hungry.

Q: Your family – like so many Americans – had deep admiration and devotion for the Kennedys. Given that adoration, it must have been painful for them to find themselves part of Kennedy’s assassination legacy. In researching the book, you uncovered letters your own father wrote to President Kennedy while a student at Harvard Law School asking to be of service. How did it feel to read those letters?

A: I guess I always knew this but started to understand it on a deeper level; the nature of the wound. It was visibly difficult for my grandmother and aunt to talk about the film because they loved the Kennedys. I didn’t find the letters my father wrote to JFK until I started the research and it explained a lot. It was completely devastating to see that letter – my young father before I was even a gleam in anyone’s eye.

Everywhere I go people tell me where they were when this happened (during the Kennedy assassination). I was speaking at an event recently, and a woman came up to me afterward with ticker tape that she picked up from the motorcade in Dallas. She had been carrying it around with her for 50 years.

The fact that it was our family and our family so loved the Kennedys and believed in them had everything to do with the choices that they made. They really did the best they could to safeguard the film. In that case, it was fortunate.

Q. How do your initial opinions about your grandfather’s film compare to your opinions after writing your book?

A: I was stunned by what a big deal the film was. Often when you are doing research on a topic you find information that is ancillary but not directly connected. I was surprised at how much information existed just on the film. For example, Don DeLillo writing in Underworld about the film; Loudon Wainwright writing about it in LIFE. It was actually the film every time.

I don’t know that I changed my opinion about it, but I was definitely surprised by it. I developed greater empathy for the people who wanted access to it and also those who wanted it to be in the safekeeping of the government. As I understood its history and its place in American life, I developed more compassion for different points of view.

There was a distinct moment for me that felt a little bit like a ground shifting moment when I realized that the reverberations of the film were so great, especially given my grandfather’s background and values. He had a disproportionate effect on American life through the choices he made about the film.

In many ways, this is a story of unintended consequences that justified the writing of the book to me. Our family had unwittingly touched a sector of American life. And that could happen to anyone. It does happen to people. You get in the crosshairs of history. That is the universal part of this story. It could happen to anybody. What would your choices be and what would the effect be of the choices you made?

Q. Besides an amazing story about the history behind the “Zapruder films,” what do you think will surprise readers of this book?

A. I think what is most surprising about it is the impact it has had in ways that you don’t realize until you trace the story. There were copyright issues. There were media dilemmas. One of the things that surprises people is how I could write 400+ pages on the Zapruder film. But I wanted to write about the legal battles, its history with LIFE magazine, Geraldo Rivera, Dan Rather, and all these famous people in American life who have crossed paths with it.

A lot of people have said to me that they were surprised by the family dynamics around the film. People didn’t know much about the story of my grandfather and my dad – the people behind the story – and how this impacted our lives.

Q: What do you think your grandfather would think about your book?

A: I think that my grandfather would be shocked to say the least that his film had the life that it did. I would hope that he would think it was the right thing to do to tell the story and that he would think that I told the story justly, fairly, and well. I think my grandfather was a wise person and understood, as my father did, that children have to come to terms with their legacy.

This interview was edited for publication.