In the face of rising polarization in the past few years, some scholars and political practitioners have argued that we need to strengthen party organizations to combat the onslaught of money from ideological groups. In theory, strengthening parties should reduce the success of political extremists because electoral parties, and the pragmatists in them, are primarily interested in winning elections and control of government. Former DCCC Executive Director William Sweeney illustrated this single-minded focus on party control when he was quoted as saying, “Our only interest was in Roll Call One [the party line vote for House Speaker that opens each Congress]. What happened in the House after that was somebody else’s responsibility.”

My research, however, suggests that party leaders and elites connected to the party have ideological preferences and choose which candidates to support based on those preferences, rather than explicitly backing moderate candidates in an attempt to win votes in the general election. This implies that party leaders who reject centrism for ideology would likely support ideologically extreme candidates. While current party leadership is relatively moderate, that could change. Strengthening parties will not necessarily guarantee more moderate candidates because as leadership changes, so too will the ideological preferences of party leaders.

One of the most notable changes to the campaign finance system since 2002 has been the movement of campaign dollars away from party organizations as the result of the McCain-Feingold campaign finance law, which banned soft money used to fund “party-building activities.” At the same time, Supreme Court decisions, such as Citizens United, have reduced regulations on outside groups. These changes have resulted in higher levels of engagement by outside organizations and have weakened the ability of party organizations to engage in electoral politics.

Some have been quick to criticize these changes as contributing to an increase in political polarization as ideologically motivated groups gain more clout in the system. These critics have argued that we should embrace campaign finance reforms that would strengthen parties. Central to this argument is the assumption that party leaders and insiders are pragmatists who are willing to sacrifice ideological principles in order to capture office. Theoretically, this pragmatic motivation should lead them to support more moderate, and thus electable, candidates. However, this assumes that party leaders are able to put aside their own ideological preferences when they assume leadership. The problem with this argument is that it fails to recognize that party leaders are not selected from a set of individuals who are free from ideological commitments and that individuals do not change their preferences just because they hold a particular position.

Indeed, my research suggests that while party leaders and party elites do prefer moderates to extremists, it is not because they are pragmatists, but rather that they sincerely hold more moderate views than the party’s base.

To examine the preferences of party leaders for moderate candidates, I examined all contested primary elections for the U.S. Senate between 2012 and 2014. Using data from the Federal Elections Commission, I connected candidates and parties through their shared donors. Connecting candidates with party donors allows me to identify the candidate preferred by the party in every primary race, even when the party committee did not explicitly endorse a candidate in the primary. This is because one of the primary purposes of party committees such as the NRSC and the DSCC is to connect wealthy and influential donors to candidates they prefer. I then combined the donor data with data on candidate ideology from Adam Bonica’s Database on Ideology and Money in Elections (DIME) to identify how party-supported candidates are different ideologically than their counterparts without party support.

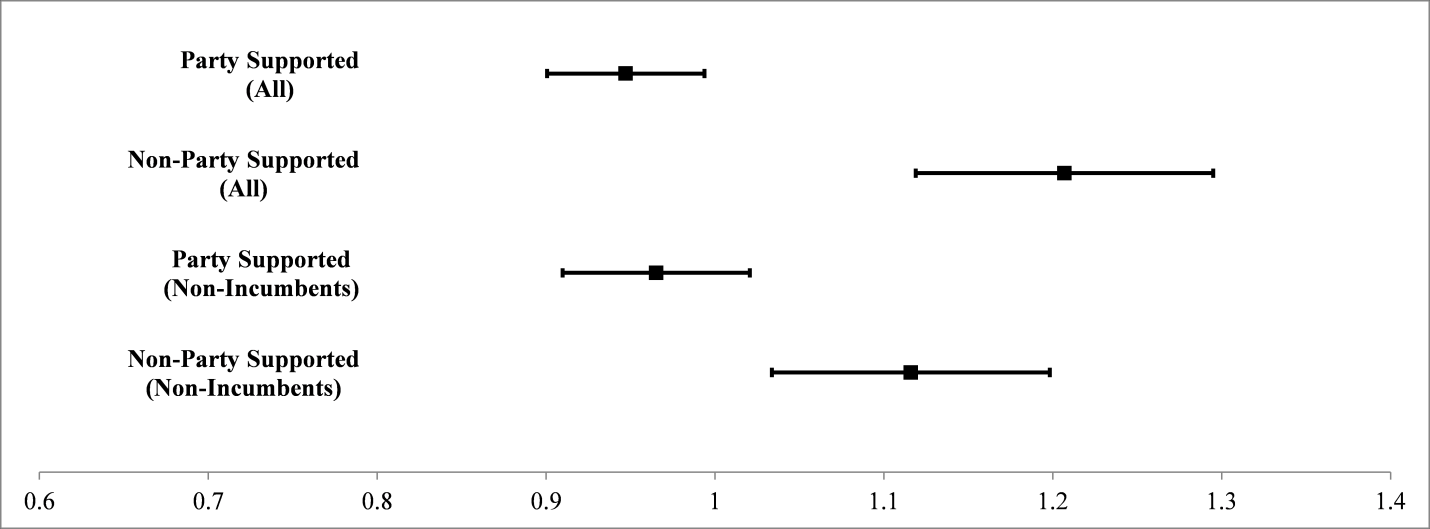

This analysis shows that less moderate candidates are more likely to have party support. Figure 1 below shows the ideological extremism of candidates with and without party support (higher numbers indicate greater extremism).

Figure 1: Ideological Differences between Party Supported and Non-Party Supported Primary Candidates

Note: Ideological extremism estimates are the absolute value of ideology point estimates calculated from candidate donations taken from DIME. 95% Confidence intervals included.

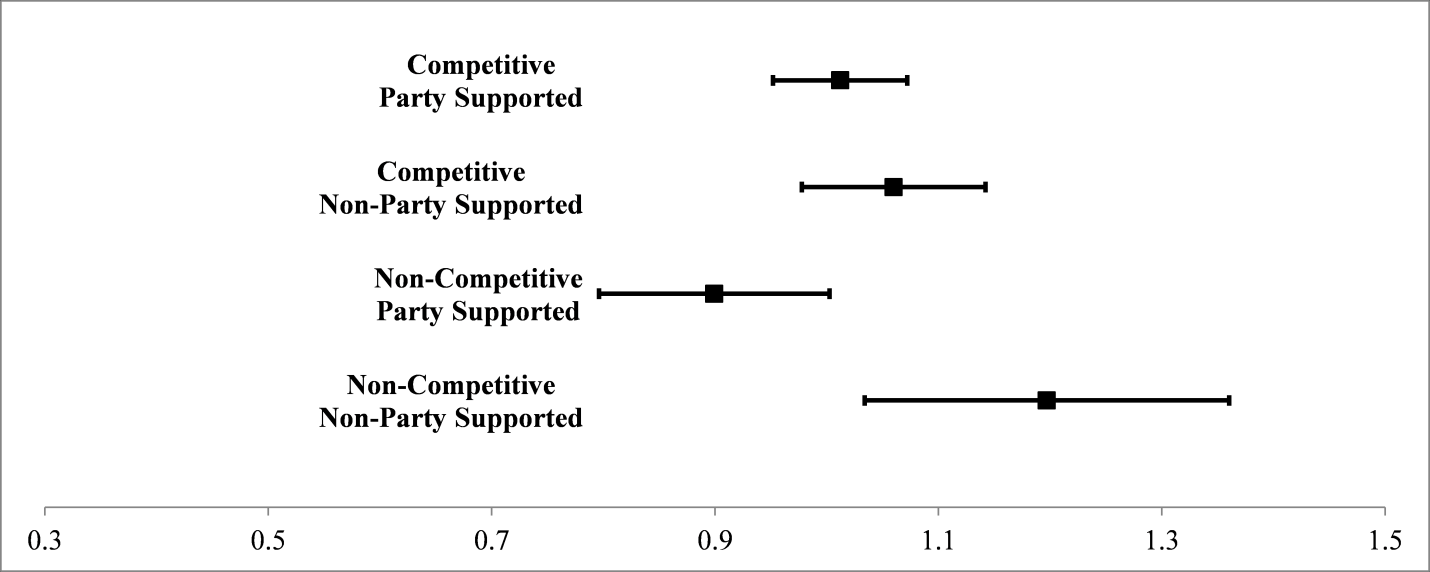

While party leaders are more likely to support more moderate candidates, the evidence suggests that those preferences are sincere rather than strategic. If parties are primarily strategic in deciding who to support, we should expect to see them most likely to support moderate candidates in swing districts. Those are the districts where changes in candidate ideology might have the biggest impact on the likelihood of winning the seat. As Figure 2 shows, this is not the case. Parties are not supporting more moderate candidates in competitive districts. Parties are, however, supporting more moderate candidates in safe and unwinnable districts where the ideology of a candidate will matter less for the likelihood of winning the seat. And in the case of safe districts, the winning candidate’s ideology could have an impact on policy outcomes and the makeup of the party’ caucus.

Figure 2: Ideological Differences Between Party Supported and Non-Party Supported Primary Candidates in Competitive and Non-Competitive States

Note: Ideological extremism estimates are the absolute value of ideology point estimates calculated from candidate donations taken from DIME. Data excludes candidates running in primaries where there is an incumbent. The top portion of the figure looks at primaries leading to general elections that Cook Political Report identified as competitive and the bottom portion of the figure looks at primaries leading to general elections that Cook Political Report identified as uncompetitive. 95% confidence intervals included.

This suggests that as party leadership changes so too will the ideological preferences of the party in choosing which candidates to support. Party organizations are not immune to hostile takeovers by groups or individuals who want to elect certain types of candidates. Strengthening parties strengthens the hand of those who control parties. Right now, those factions appear to be more moderate than other factions within the parties, however, there is no guarantee that will remain the case going forward.

Hans Hassell is Assistant Professor of Politics at Cornell College, and author of the recent book, "The Party’s Primary: Control of Congressional Nominations."

|

Purchasing Power: The ConversationThis post is part of the special series designed to provide well-informed commentary, fresh questions, and new answers about the facts of money in politics. Dive in to 'Purchasing Power: The Conversation’ here. The views expressed by blog contributors are the authors’ own and not necessarily the views of the Brennan Center.

|