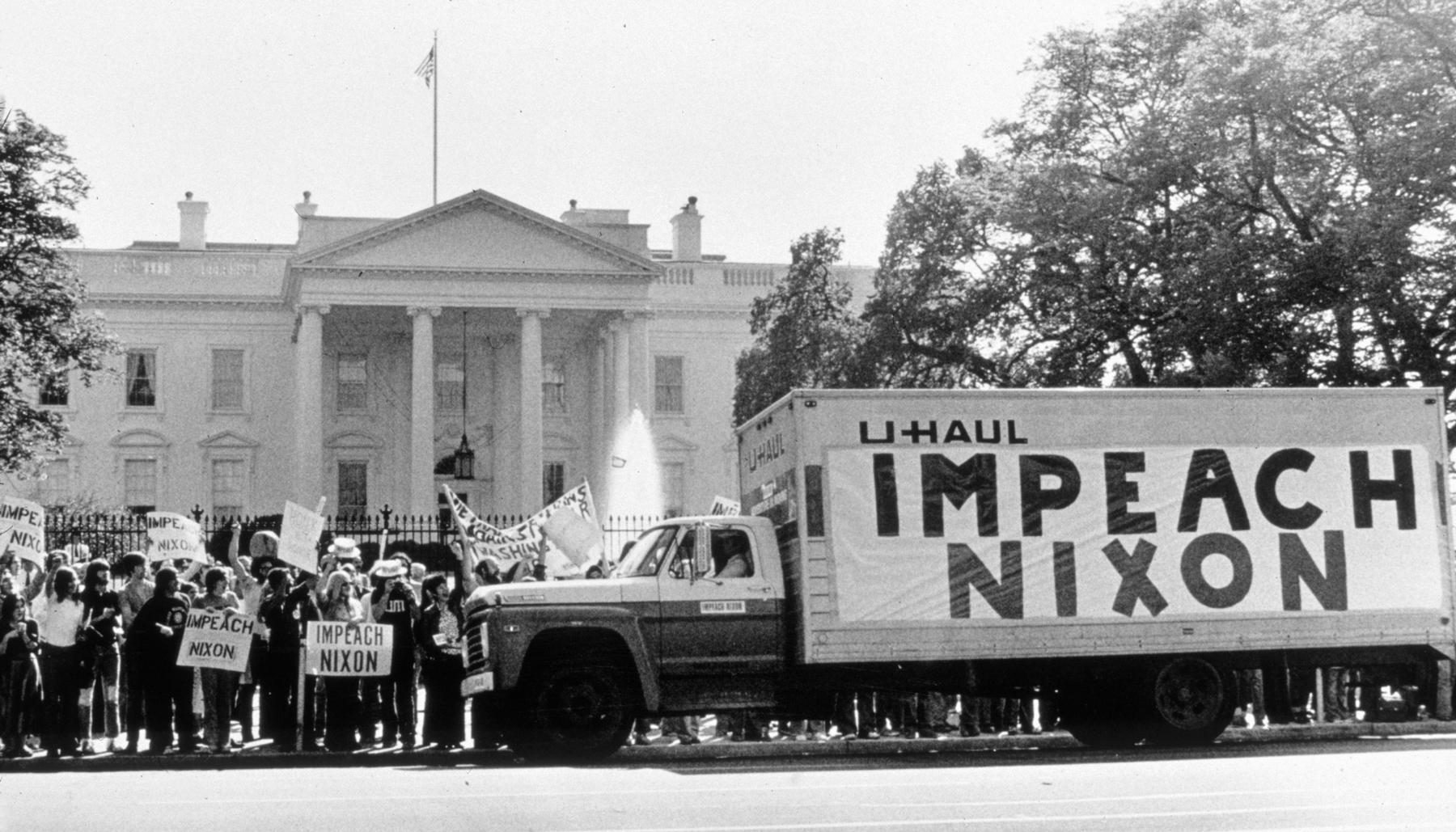

If impeachment won’t cure an abuse of presidential power, what will?

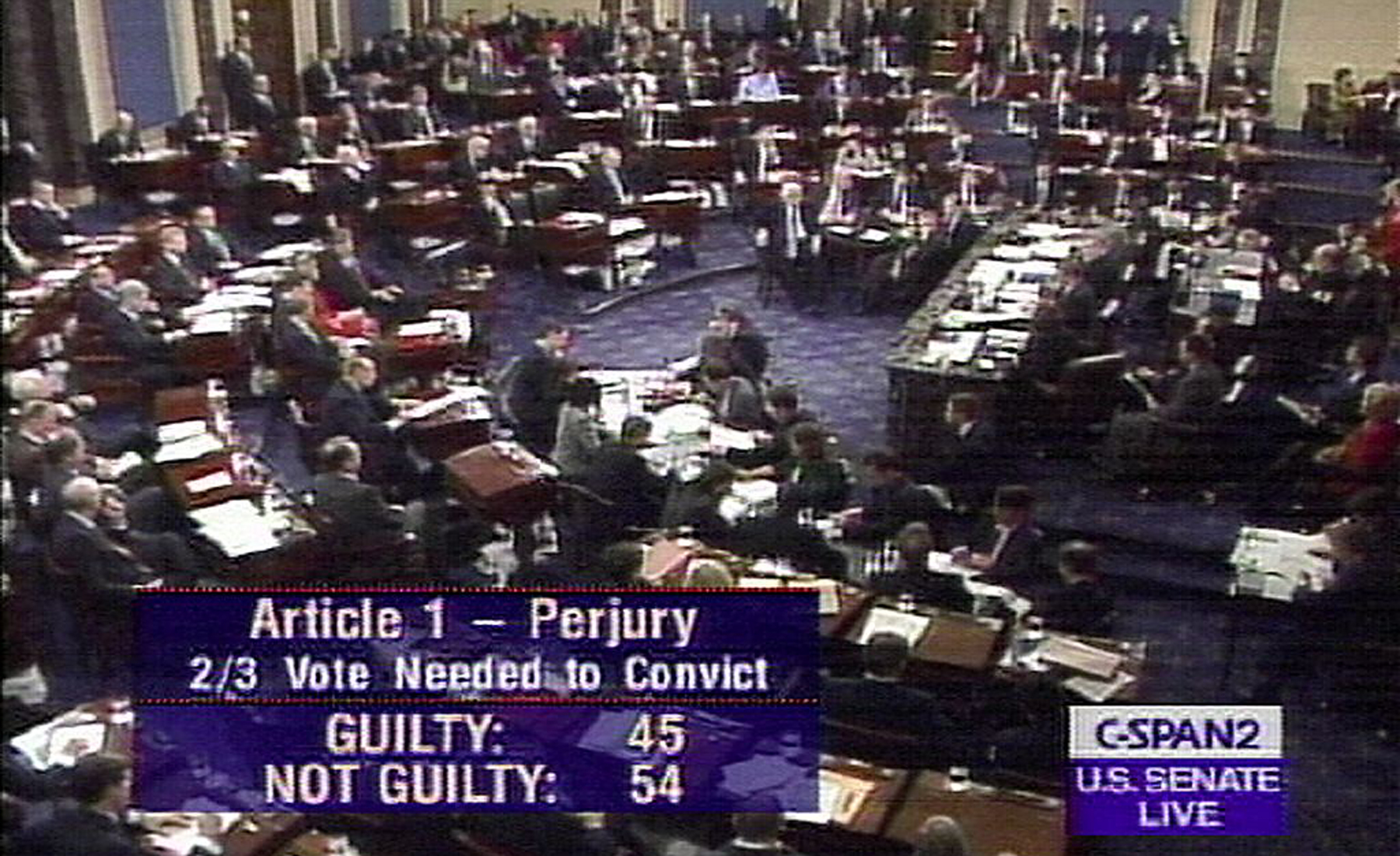

Some scholars argue that even without removal, impeachment still serves a purpose. New comparative research from Tom Ginsburg, Aziz Huq, and David Landau on impeachment provides “the first comprehensive analysis of how constitutions globally have addressed [removals], and what the consequences of different design choices are likely to be.” Looking at a large data set regarding impeachment and removal along with case studies of South Korea, Brazil, Paraguay, South Africa, and the United States, they argue that impeachment allows presidential or semi-presidential systems to get out of a major crisis.

However, this “exit” from crises works best when the process of impeachment culminates in new elections immediately or soon after a head of state is impeached. In South Korea for example, new elections must be called 60 days after the impeachment process has concluded. Huq, Ginsburg, and Landau argue that this process allows a reboot of the system.

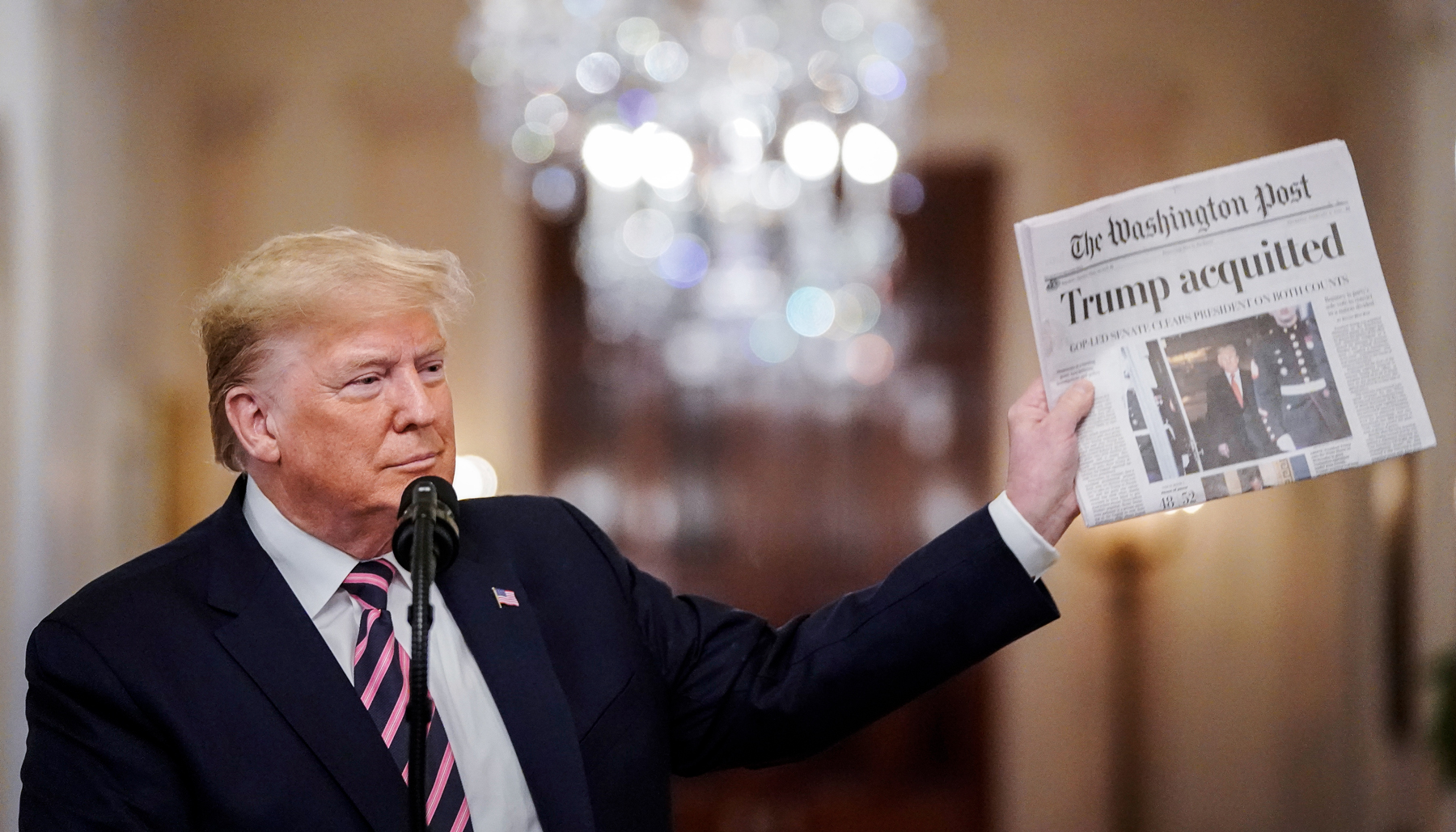

In the United States, we do not have such an immediate-election requirement — but we did coincidentally hold elections last November. What can this tell us about whether impeachment can provide this cleansing process? Some might say the election’s outcome proved that here too impeachment can serve such purpose. But because our election occurred only because the calendar dictated, we cannot rest on this comforting conclusion.

Some commentators believed that a “reset” election would allow Americans to say, definitively, “Trump is not who we are.” To serve as a reset, impeachment ought to result from elections that reflect the popular verdict — who we actually are and what we actually believe — about a president’s conduct.

It is fair to say that the last election reflected “who we are.” More than 159 million people voted in the 2020 federal election and 2021 Senate runoffs, the highest voter turnout in more than a century. As we have noted elsewhere, voters gave Democrats “trifecta” leadership of the White House, the Senate, and the House — a definitive rebuke of Trump and his congressional backers.

But even if the 2020 election was a cure, there’s little guarantee that future elections will be, given the ways Republicans are seeking to undermine elections in the Senate and state legislatures.

Contrary to the intent of the Constitution’s authors, Congress responds to issues slowly — or not at all — because the Senate does not represent the population, but rather states, and the House is gerrymandered to a fare-thee-well. Senators from low-population states — more likely rural, white, conservative, and Republican — are at least as powerful as senators from higher-population states, in part because they represent more homogeneous interests. Further, the arcane Senate rule of the filibuster exaggerates the already antidemocratic nature of the body. So proposed federal initiatives to fix problems of democracy laid bare by the last election — by easing voter registration, preventing or curing partisan gerrymandering, and making voting itself more accessible — are stymied by the ability of the Republican minority to deny a filibuster-proof supermajority in the Senate.

Worse, where Republicans are in control of state governments, they are changing the rules to make it harder to vote, especially for people of color. Republican legislators and other Republican officials, including several governors, assert that these new restrictions on voting will restore public confidence in “election integrity.” Their assertion, however, is unsupported by any evidence of election-security breaches anywhere in the country sufficient to change the national or state-level outcomes of the 2020–21 elections.

Republican-controlled states around the country have enacted vote-suppression laws. Georgia enacted legislation this year that prohibits and criminalizes “line-warming”— the provision of food, water, and blankets by individuals or groups to voters standing in line, often for hours, while waiting to vote at their polling stations. Florida’s governor signed new legislation that also will restrict line-warming. Another repeated focus of these laws is voting on the Sunday before Election Day. As voting-rights experts and others have noted, the probable target of these prohibitions is “Souls to the Polls” — the custom among Black churches to organize congregants to vote together after services.

Republican-controlled states are attacking other turnout-boosting practices as well. For example, Florida now prohibits individuals or groups from collecting mail-in ballots from voters for delivery to drop boxes, mailboxes, or polling places. Florida’s legislation criminalizes any person’s possession of “two or more mail ballots other than the person’s own ballot and an immediate family member’s.”

By and large, Republicans reject the view that democracy is our constitutional model of government. Many have stated for a long time that the United States is a “republic” and not a “democracy.” Of course, this proposition begs the question about who should be able to vote, and how easily.

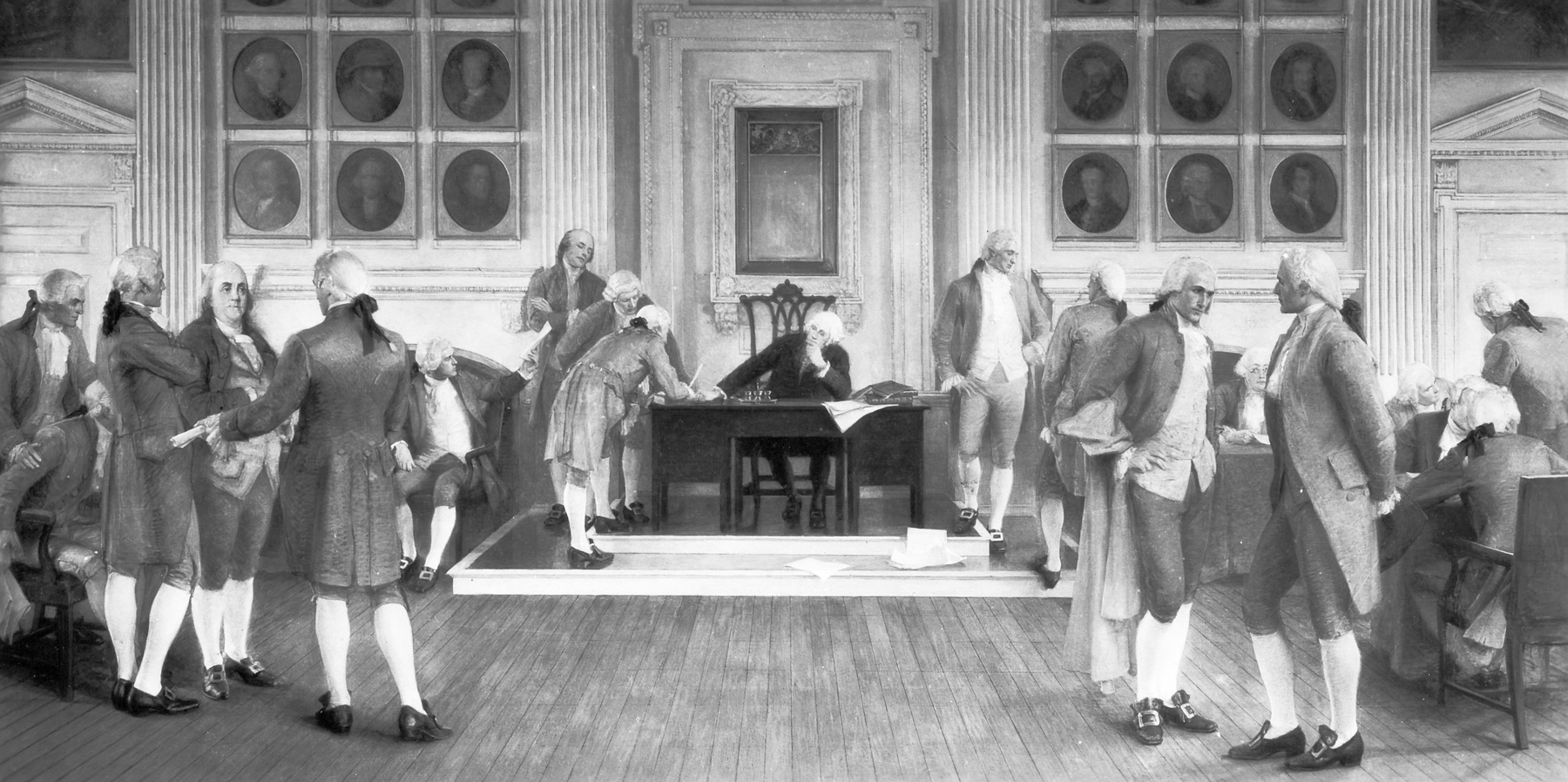

Indeed, it is ironic that Republicans appear to believe that constricting the availability of the franchise serves the small-r republican model of government. In Federalist No. 10, where Madison argued for the superiority of the republican form of representative government (relative to the purely democratic form) to mute the power of faction, he also contended that larger republics were superior to smaller republics:

The smaller the society, the fewer probably will be the distinct parties and interests composing it; the fewer the distinct parties and interests, the more frequently will a majority be found of the same party; and the smaller the number of individuals composing a majority, and the smaller the compass within which they are placed, the more easily will they concert and execute their plans of oppression. Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other. Besides other impediments, it may be remarked that, where there is a consciousness of unjust or dishonorable purposes, communication is always checked by distrust in proportion to the number whose concurrence is necessary. Hence, it clearly appears, that the same advantage which a republic has over a democracy, in controlling the effects of faction, is enjoyed by a large over a small republic. [emphasis added]

It thus follows that, all else being equal, increasing the number of voters would make factions less powerful. Nevertheless, Republicans want to enact new limits on access to the polls, particularly directed at urban and younger voters and at voters of color, who tend not to support their party. Republicans aim to make it harder for these groups to vote, thereby trying to stave off a demographic and ideological challenge to white patriarchy in America.

The more Republicans restrict voting (by, for example, cutting voting days and hours, eliminating voting sites, prohibiting line-warming and ballot collection for homebound voters and for those lacking transportation to distant polling sites), the more they will be able to reduce or deter voter turnout. In this way, they lock in their gains for the long term. In their view, to the victors go the spoils — or, under these new vote-suppression laws, the ballots.