This was originally published by Slate.

Even before the first vote in the 2024 election is cast, partisan extremists are jockeying for the opportunity to potentially subvert the outcome. Georgia is the eye of the storm. Last week, Georgia’s Republican-controlled State Election Board voted to give county boards the unprecedented authority to second-guess election officials before certifying election results. This move—which could pave the way for unwarranted delays and refusals to certify an adverse vote—is part of a national effort to empower partisans to steal the election if they don’t like the results. But make no mistake: While alarming and dangerous, none of this maneuvering will make legal what is not, including any plot to thwart an election.

The new Georgia regulation follows the failed scheme to overturn the 2020 election and is part of a larger election subversion campaign playing out across the country. In Georgia, Arizona, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, and other key battleground states, lawmakers have passed laws inviting partisan interference in election administration or electoral outcomes. In these states and others, right-wing activists have sought to force unreliable hand counting of all ballots and contests even in large jurisdictions, a move that would introduce error into the process and dramatically slow down results. And election deniers are filing lawsuits across the country asking courts to greenlight attacks on certification, throw out votes, or change election procedures based on unsubstantiated conspiracy theories. All these actions seek to lay the groundwork to try to justify throwing out legitimate election results. While the effort this year is more widespread and better funded than the effort by Donald Trump and his allies to overturn his loss in the 2020 election, it is no more legal than the 2020 effort.

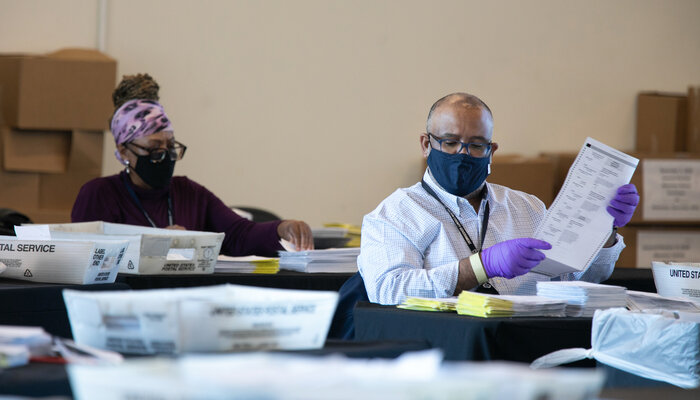

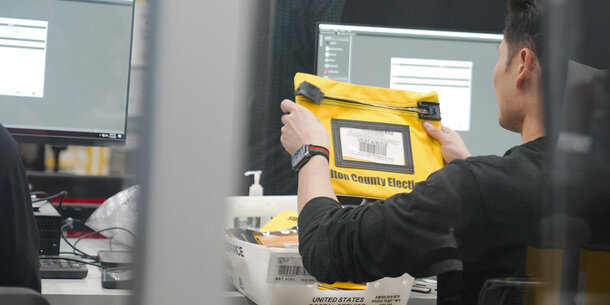

Back in Georgia, the focus has now turned to election certification, an obscure but ceremonial step at the end of the election process to make the results official. Earlier this year, a member of the Fulton County Election Board refused to certify the primary election results unless she could review troves of election data. She even filed a lawsuit asking a court to grant her that power despite over a century of law and practice to the contrary, as we explain in our friend-of-the-court brief.

Then the five-member State Election Board, controlled by three members who publicly questioned the 2020 election results, joined the fray. Egged on by Trump, who praised the three members in the majority by name at a rally in Georgia, the board has voted to turn certification into an opportunity for conspiracy theorists and partisans to block the will of the people.

The state board’s rule, along with the Fulton County board member’s stalling tactics, are wholly inappropriate. In Georgia, election boards aren’t generally involved in election administration, and they do not weigh in on the count for a reason. A handful of political appointees are not and should not be empowered to take matters into their own hands to reject an election outcome. The role of boards is ministerial; they are there to certify elections, not to reinvestigate their details. The law in Georgia, and the law in every state, is clear: certification is a mandatory act. Any election disputes or contests are handled by the courts, which provide formal processes and are equipped to evaluate evidence and interpret the law.

Any claim of authority by any state or local official to deny or overturn election results is unlawful. Despite the smokescreen, numerous federal and state laws prohibit officials from negating the will of the people to help elect their preferred candidates. The U.S. Constitution and all state constitutions protect voting rights and the due process of voters, and federal law makes it a crime to conspire to deprive individuals of their votes, among other protections. In the past few years, courts have ruled against officials in several battleground states trying to deny or delay certification and candidates trying to overturn results. In each instance, certification was eventually mandated because the law requires it. The certification charade in Georgia is nothing more than an attempt to put a veneer of legality over illegal conduct. We should not be duped.

If enough Americans buy the ruse that our election system allows for this kind of manipulation, then it will be easier for wrongdoers to get away with it. For this reason, the main advocacy target of this disinformation-fueled plot is the American people. To be sure, we must strengthen our legal safeguards so that it is harder to promote these scams in the future; passing the Freedom to Vote Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, currently pending in Congress, is a critical step to prevent all sorts of shenanigans. But even without additional safeguards, our current institutions can and should repel election subversion plots if Americans remain vigilant.

Supporters of free and fair elections can hold the line if we pay attention and demand adherence to the law—taking it to the courts (who can order compliance with the law), to state election authorities (who typically oversee statewide counts and can help protect the system against rogue local actors), to governors (who typically certify presidential election victors), and ultimately to the American people (who are the final arbiters of the legitimacy of elections). Any plot to subvert election results would require failures to uphold the law on multiple levels.

Even then, if the public sees these plots for what they really are, then they will not succeed. We must not give credence to the fallacy that it is possible to find legitimate loopholes to accepting the will of the voters.