Cross-posted from The Washington Post.

Democrats will pick up at least 26 seats and take a majority in the House of Representatives if the preliminary results from Tuesday’s midterm elections hold. But partisan gerrymandering is still a major issue. Our analysis of one state’s results shows that the party would almost certainly have won more if Republicans hadn’t deliberately drawn districts to limit Democratic chances.

North Carolina’s congressional district lines are already the subject of federal litigation claiming that they give Republicans a systematic, unconstitutional advantage in winning seats. Tuesday’s results bear those claims out. Democrats won roughly 50 percent of the vote in North Carolina, their best performance in almost a decade. But despite an extraordinary year, they netted just three of the state’s 13 congressional seats — the same as in 2014 and 2016. That happened because a promising Democratic wave crashed against one of the country’s most extreme gerrymanders, a congressional map that Republican legislators brazenly stated on the record that they carefully crafted “to give a partisan advantage to 10 Republicans and 3 Democrats.”

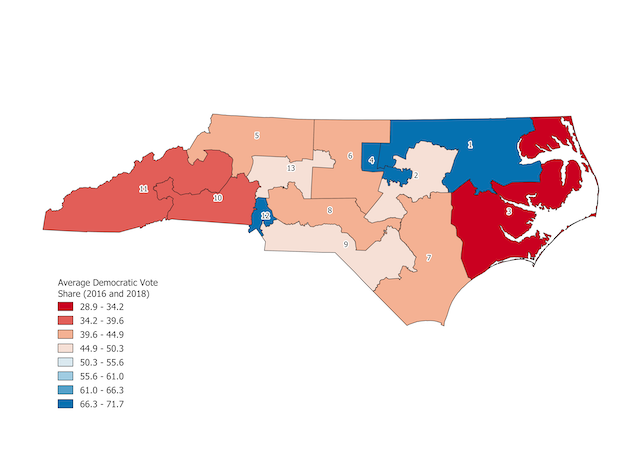

To engineer this advantage, the leaders of the Republican caucus worked in secret with a consultant to pack likely Democrats into three super-blue districts. In each of these districts, Democrats would win by very large margins. The Republican mapmakers then spread the rest of the state’s Democrats more thinly across the remaining 10 districts, ensuring that Republican candidates would win by small, but safe, margins. They made many of these districts safe for the GOP by giving each one just enough Republican voters to win elections in normal years.

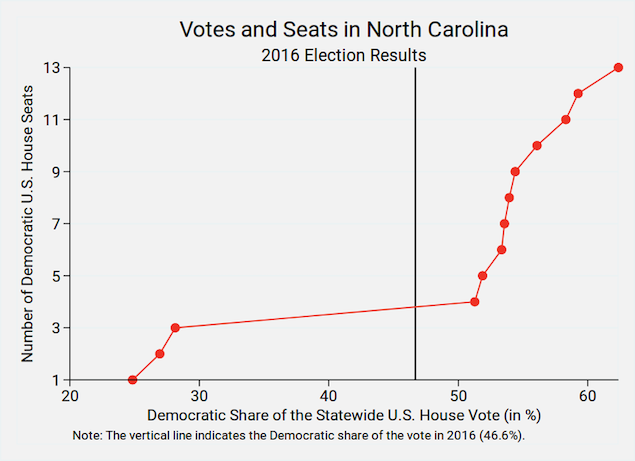

With this scientific slicing and dicing of voters, it didn’t matter if Democrats got 30 percent of the statewide vote or 50 percent, as they did this year. The figure below shows the share of the statewide vote at which the Democrats would be expected to win each of the districts. They are guaranteed wins in three districts but then face a tremendously steep climb to win any additional seats. In fact, they didn’t stand a chance of picking up a fourth seat unless they could net 52.5 percent of the statewide vote, something they achieved only once since 2000, in the 2008 election.

In 2016, the Republicans’ map handed 10 seats to the GOP despite a strong Democratic year that saw Roy Cooper win the governor’s mansion and Democrats sweep to other statewide wins.

Increased Democratic votes were mostly wasted in the state’s three reliably blue districts. Indeed, the Democrats’ average margin of victory in these three districts rose from 18 percentage points in 2016 to an astonishing 23 points in 2018. Still, running up the vote in those districts didn’t send any more Democrats from North Carolina to Congress. The Republicans’ packing strategy worked just as they’d planned.

Meanwhile, in the state’s Republican districts, Democrats were spread too thin for even a robust increase in support to help. All in all, Republicans won their districts with an average margin of six points, showing the Republicans’ cracking strategy also playing out as intended. The map below shows the average vote share won by Democrats in North Carolina districts in the past two congressional elections.

All of this has continued to leave North Carolina Democrats with only 23 percent of the congressional delegation even though they won roughly half of the state’s votes in House races. Indeed, despite North Carolina’s well-established purple-state status — with hotly contested elections for statewide offices and a vibrant, diverse collection of voices and interests — its congressional delegation remains overwhelmingly Republican. And that goes back to the basic design of the map.

The only way to put a stop to this is to remake North Carolina’s map and the state’s redistricting process. The Supreme Court can help do both this spring by striking down the map as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander and putting some laws in place to limit the worst redistricting abuses. A strong ruling from the court would not only require the legislature to draw a new, fairer map for 2020 but also set the ground rules for the next round of redistricting in 2021. If the Supreme Court refuses to rule, the North Carolina Supreme Court might.

And while North Carolinians don’t have access to the kind of ballot initiatives that put independent redistricting commissions in place in California and Michigan, there might be some hope for legislative reforms ahead of 2021, if Republicans become sufficiently scared that a blue tsunami in 2020 could sweep away their long-standing majority in the state legislature and, with it, their control over the state’s next redistricting process. The threat of a Democratic gerrymander in 2021 might be enough to put the state’s Republicans in a bargaining mood. Certainly in the long run, the demographics of this fast-changing state don’t favor Republicans.

However, until courts or civic-minded legislators step in to fix a broken redistricting process, the gerrymander is still very much threatening American democracy.

(Photo: Alex Wong/Getty; chart & map: Brennan Center)