Treating All Kids as Kids

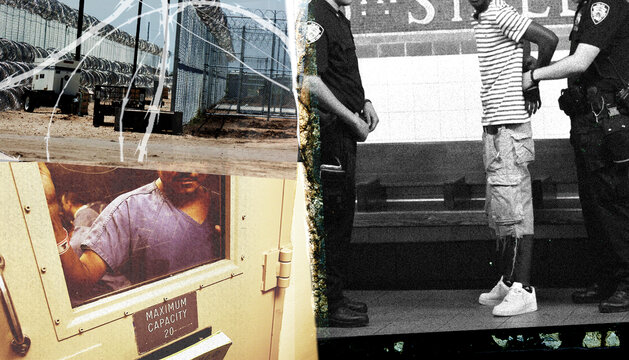

Persistent and longstanding racism has fueled harsher treatment of young Black people in the justice system.

Part of

This essay is part of the Brennan Center’s series examining the punitive excess that has come to define America’s criminal legal system.

America’s mistreatment of Black children is chronic and casual. Sadly, it is an American phenomenon — a handed-down thing — that is deeply rooted in American soil and in the American psyche. Virtually every system that touches Black children in this country — public schools, foster care, immigration — treats them more harshly than white children. Arguably, though, the most acute harm occurs in the criminal justice system, where we routinely exercise the power to designate and derail.

On a daily basis, the system prematurely labels Black children as adults, ignoring the child in the offender. We carelessly discard young Black offenders in a structure never designed for children. There, these young people lose much more than their freedom. They lose the opportunity to develop in a healthier environment. They can expect lifelong challenges associated with less education, increased mental health problems, higher rates of suicide, and greater financial instability. To interrupt this persistent pattern of mistreatment, we need to adopt a bright line rule prohibiting the prosecution of anyone under 21 in the adult criminal justice system.

Children have the right to be children. But our criminal justice system routinely ignores that reality when applied to Black children. Both brain science and common sense confirm that an adolescent’s act differs significantly from that of a mature adult. Adolescents are works in progress who exhibit signature traits. They are impulsive, they have greater difficulty recognizing and regulating emotional responses, and they fail to appreciate fully the risks of their behavior, favoring short-term rewards over potential costs. Adolescents succumb more readily to negative external influences such as the behavior of peers — even their very presence, in fact — and the influence of unstable environments.

But neuroscience tells us that the regions of the adolescent brain governing impulse control and risk avoidance have not yet fully formed. The good news is that these traits are not fixed; volatility and impetuosity are transitory. As young people mature into their mid-20s, they are better able to resist emotional impulses and regulate their behavior thanks to the development of brain structures and systems involved in executive function and impulse control. By the time young people reach their mid-20s, most will stop engaging in criminal conduct.

In recent years, this evidence has begun to persuade a growing number of courts and policymakers to question the national reflex to designate younger and younger people as adults in the criminal justice system. But the dark underbelly of that hopeful story is that not all children enjoy the benefits of that new approach. Even as we experience a reduction in our youth justice population, racial disparities persist. The prism of race distorts our perception of the Black youthful offender and misshapes the Black child’s experience of justice. Three intersecting phenomena are at play: stereotypical assumptions, dehumanization, and “adultification.”

The “Black person as criminal” stereotype, which equates dangerousness with skin color, has demonstrated remarkable resilience over time. It persists even in light of conflicting data. Indeed, the narrative is so pervasive and culturally ingrained in America that we implicitly make the connection even when we explicitly reject the view. We see young Black offenders as animals or savages who engage in “wilding” behavior. The process of dehumanization turns Black children into undifferentiated objects. It deprives them of their individual features, those qualities that make them valuable and unique. Instead, we brand them as nameless predators.

When we add adultification to the mix, the justice experience for Black children warps even further. Research reveals that we see Black boys and girls as older than their actual chronological age. Participants in a series of comprehensive studies misperceived 13-year-old Black boys as 17-year-olds. Just as importantly, the older that the participants considered the child, the more culpable the child seemed. In a separate set of studies of Black girls, respondents considered Black girls more adult than white girls at almost all stages of development. That adultification led respondents to conclude that Black girls needed less nurturing and protection than their white peers. The bottom line is simple: together, these phenomena prematurely strip Black children of the privilege and protections of childhood, provoking dangerous ramifications for them in the justice context.

We can trace an indelible through-line from this country’s racist origins to today’s racialized mistreatment of young people in our justice system. During slavery, white slavers separated Black children from their mothers because a child could garner a greater profit. This was not just profiteering; it was an explicit insistence that Black children were chattel, not human. During Jim Crow, white mobs lynched Black children if they dared cross a racial boundary that white society invented and ruthlessly enforced. Again, the declaration: Black children were not like other children. They needed to “know their place” in the racial caste or risk the ultimate sanction. Our history primed this nation to expect and accept the disparate treatment of Black children as somehow appropriate or deserved.

The 20th century justice system delivered on that expectation. Politicians, academics, and the media created and spread a “superpredator” mythology forecasting a tidal wave of violence by a new breed of offenders. This mythology contended that Black children were more predatory, more dangerous, more adult-like than white children. Although juvenile crime rates actually dropped in this period, the threat stoked fear that white America was in danger. That mischaracterization allowed Americans to withstand any tug of moral constraint in the rush to charge Black children as adults in the criminal justice system — children as young as nine. Politicians pushed “adult time for adult crime” legislation and then filled our prisons with young Black kids.

Even as recently as the summer of 2020, we continue to trip over reminders of this racialized treatment. When a white 17-year-old, Kyle Rittenhouse, opened fire on protesters in Kenosha, Wisconsin, killing two protesters, conservative pundits and political operatives were quick to describe him as a “little boy out there trying to protect his community.” Even when he walked past police toting a semi-automatic rifle, they did not stop or question him; almost certainly, an armed Black 17-year-old would not have lived to tell the story. But Rittenhouse was not perceived as dangerous. He was seen as a child. Contrast that with 12-year-old Tamir Rice, a child playing with a toy gun in his neighborhood park. A Cleveland police officer sized up Tamir in an instant. He considered him dangerous, shooting and killing him within two seconds of getting out of his patrol car — evidence, once again, of the pernicious power of racialized perceptions in our discretionary calls.

Retaining the discretion to charge a young offender in adult court leads to an untenable form of racial exceptionalism: an adolescent’s signature traits will be treated as “mitigating qualities” unless the offender is Black. Adolescent characteristics skew differently when we add race to the mix. Impulsivity morphs into dangerous unpredictability. Misbehavior in the company of peers becomes “gang activity.” The inability to appreciate long-term risks devolves into intrinsic irresponsibility. So long as we allow the discretionary call to charge some offenders in the adult system, we will continue to see prosecutors in juvenile court weaponizing adult prosecution as a way to coerce a more severe outcome in juvenile court. We will continue to see Black kids shouldered out of rehabilitative care even when they engage in the exact same behavior as white children. We will continue to see prosecutors misperceiving Black children’s wrongful conduct as willful rather than the product of immaturity. Breaking this racism habit requires us to prohibit the prosecution of anyone under 21 in the adult criminal system.

Kim Taylor-Thompson is a professor of clinical law emerita at NYU School of Law.

More from the Punitive Excess series

-

What Did You Call Me?

An incarcerated person writes about how dehumanizing language like “inmate” is destructive. -

The Federal Funding that Fuels Mass Incarceration

Decades of financial incentives by the federal government have encouraged states and cities to put more people behind bars for longer, with devastating results. -

Covid-19 and the Struggle for Health Behind Bars

For many, harming the health of people in prison appears to have become part of their punishment. That needs to change.