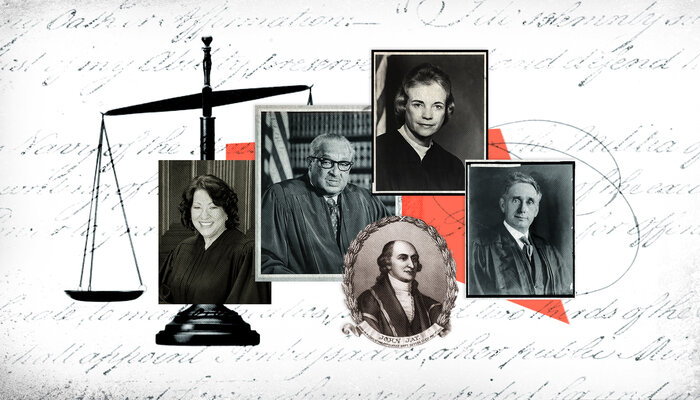

The First Six Supreme Court Justices

Article III of the Constitution organized the federal judiciary into one “supreme Court” and however many “inferior Courts” Congress chooses to create, but overall, it was surprisingly sparse on details. Clocking in at under 400 words — the shortest of the articles of the Constitution creating the three branches of government — the framers provided little detail on the powers and responsibilities of the Supreme Court. The Judiciary Act of 1789 filled in some of the blanks, laying the groundwork for what would become the modern U.S. legal system. Signed by George Washington, the act established a six-member Supreme Court — comprised of one chief justice and five associate justices — as well as the position of attorney general.

As the first president, Washington appointed more members of the Court than any other U.S. president, selecting a total of eight associate justices and three chief justices (one of whom failed to be confirmed by the Senate) during his tenure. His first six appointees were a mix of allies and prominent public figures whose reputations would help establish the nascent Court’s legitimacy.

- John Jay (chief justice). A close ally of Washington and an ardent Federalist, Jay helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War with Great Britain, then served as secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation. While chief justice, Jay was also busy running for governor of New York (twice) and negotiating the unpopular “Jay Treaty” with Great Britain. When he was elected governor in 1795, Jay resigned from the Court.

- John Blair Jr. Blair earned his reputation as a fair and skilled jurist while serving on the Virginia Court of Appeals, where he established the principle of “judicial review,” referring to the ability of the courts to invalidate an act of the legislature or executive that violates the Constitution. In his less than six years on the Supreme Court, Blair heard only 13 cases and resigned in 1796 over health concerns.

- William Cushing. By far the most experienced jurist of Washington’s first six appointees, Cushing, seated at age 57, had been a Massachusetts judge since he was 28 years old. He was a man of few words — his shortest Supreme Court opinion was just two sentences long — but he was also the longest-serving of the Court’s original members. Washington even tapped him to succeed Jay as chief justice, but Cushing stepped down from the role after only a week due to health concerns. He remained on the bench as an associate justice until his death in 1810.

- Robert Hanson Harrison. Another close ally of Washington, having been his aide-de-camp and military secretary during the Revolution, Harrison never actually served as a Supreme Court justice. He was too sick to accept the appointment and died a few months after the Court’s first meeting in 1790. Washington ultimately appointed James Iredell, a North Carolina jurist and Federalist leader, to fill Harrison’s seat.

- John Rutledge. A respected figure from South Carolina, Rutledge missed the first meetings of the Supreme Court due to illness and only heard a few cases on the southern circuit before resigning in 1791. When John Jay retired, Washington granted Rutledge’s request to be named the interim chief justice. Upon returning from recess, the Senate blocked his permanent appointment less than six months later, citing Rutledge’s unhinged rhetoric against the Jay Treaty, including an infamous declaration that he would rather Washington die than sign it. Rutledge was so upset by the news that he attempted suicide by throwing himself into the Charleston Bay, but two enslaved men pulled him to safety. His public career, however, did not survive the incident.

- James Wilson. Wilson holds the distinction of being the only Supreme Court justice to have signed both the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. An influential member of the Constitutional Convention — he helped create both the Electoral College and the Three-fifths Compromise — Wilson was ultimately derailed by financial troubles. He was jailed twice for unpaid land debts while serving on the bench.

The Court’s first six members were confirmed by the Senate within two days of their nomination — a feat that would be virtually impossible today given the fraught and polarized judicial confirmation processes that have been the norm in recent decades.

The Supreme Court was scheduled to meet for the first time on February 1, 1790, at the Royal Exchange building in New York City, which was the nation’s capital at the time. The meeting was pushed back because of travel delays, and ultimately, only four of the six justices were able to attend. It was an inauspicious start for the highest court of the United States.