Voters in the Sunshine State achieved a major win for American democracy today. By passing Amendment 4, voters changed the state constitution and restored the right to vote to citizens with felony convictions in their past who have finished serving their sentences. This is no small number — some 1.4 million individuals living and working in the state will now have the opportunity to have their voices heard in their communities. Changes to voting rights of this magnitude are few and far between. Not since the 26th Amendment lowered the voting age to 18 in 1971 has a single change in the law extended the franchise to so many in the United States at once.

This season has seen an aggressive effort to restrict access to the ballot box — from purges in Georgia and Alabama to new restrictive voter ID laws in North Dakota, proponents of a less inclusive democracy exerted their power in troubling ways. In that context, there is even more cause to celebrate the passage of the Voting Restoration Amendment in Florida. What’s more, this was a cause embraced by voters of all political stripes; while the races for governor and senator are neck-and-neck, the Voting Restoration Amendment was supported by more than 63 percent of Florida’s voters.

In order to truly appreciate the impact that this will have on Florida’s democracy, it is important that we recall the roots of the old system, and the terrible consequences it had. And in order to ensure that the restoration of voting rights to so many actually results in new voters and a more inclusive political conversation, we must prepare to do the important work of welcoming returning citizens to the conversation in the months to come.

Racial Impacts of Florida’s Old System

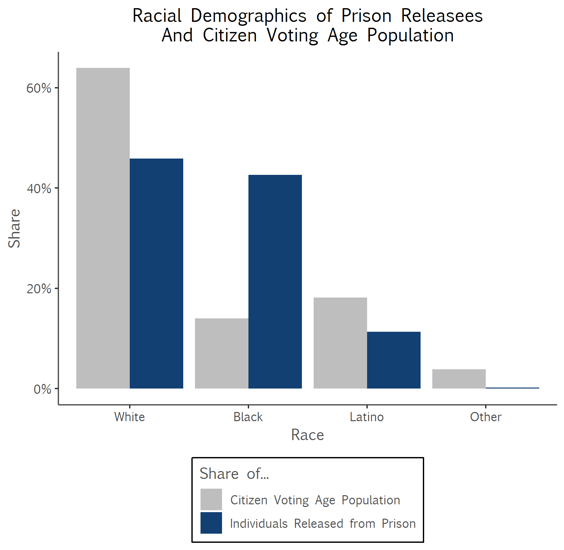

By linking voting rights to racist criminal laws known as the “Black Code” during the Reconstruction era, Florida’s felony disenfranchisement law, written into the state’s 1868 constitution, was originally intended to disenfranchise black citizens. That is exactly what it did, even 150 years later. Although black individuals make up just 14 percent of the citizen voting-age population in Florida, they constituted 42 percent of individuals released from prison between 2016 and 2017. Researchers have estimated that nearly one in four black males were permanently disenfranchised due to a felony conviction, compared to fewer than one in 10 white men.

This had enormous ramifications for Florida’s electorate: Just 75 percent of black men are registered, versus 89 percent of white men. There are, of course, other factors at play — on average, black men graduate from college at lower rates and earn less money than white men, both of which are correlated with lower registration rates. But that’s true for black women vis-à-vis white women, too, and their registration rates are much closer. Since women of all races are less likely to be impacted by felony disenfranchisement rules, there is good reason to believe that much of the registration gap among men was driven by these rules.

Problems with Discretionary Re-Enfranchisement Policies

Disparities in the criminal justice system weren’t the only way in which felony disenfranchisement laws had outsized consequences for Florida’s black voters. Gov. Rick Scott’s discretionary process for rights restoration further exacerbated these consequences.

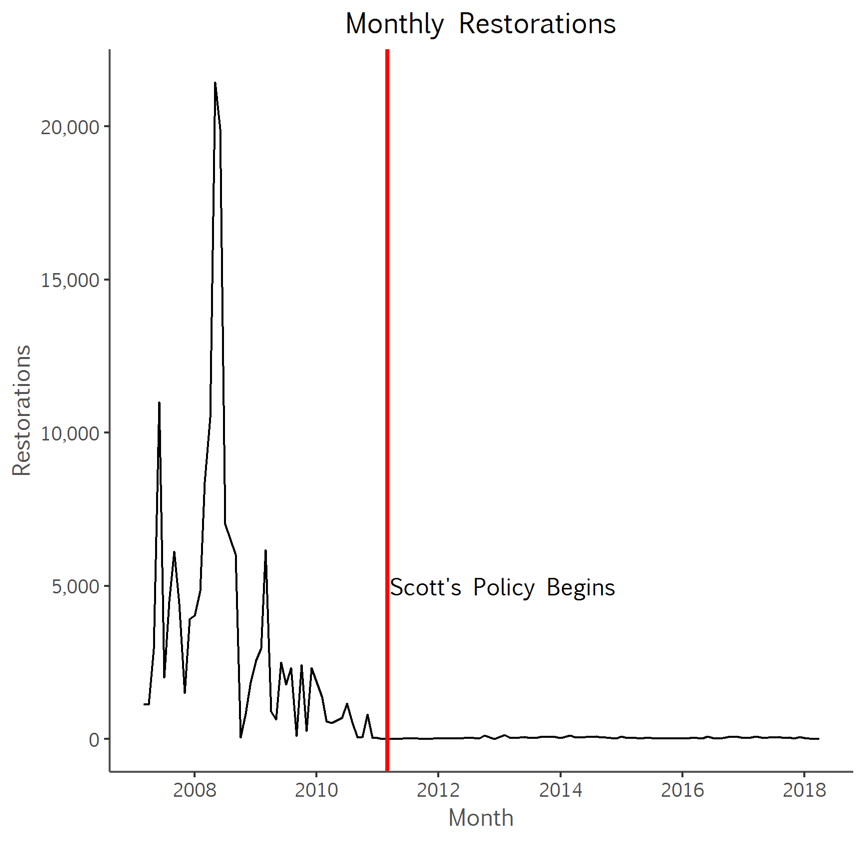

Gov. Charlie Crist (Scott’s predecessor) instituted a policy automatically restoring voting rights for some of Florida’s returning citizens. This policy, based largely on the severity of the crime committed by an individual, was in place from April of 2007 until it was ended by Rick Scott in March of 2011. During that period of just under four years, more than 150,000 Floridians with felony convictions had their voting rights restored. There is not publicly available data on the race of all those people. But using data from the voter file, we know the race of the formerly incarcerated people (but not people sentenced to felony probation) whose rights were restored and that went on to register. Of those individuals who eventually went on to register, more than half were black, and 37 percent were white. Although exact numbers about the demographics of the disenfranchised population in Florida are hard to come by, these shares are broadly reflective of the disenfranchised population as a whole.

In 2011, Gov. Scott ended the automatic process for rights restoration. Instead, returned citizens were required to apply to the Clemency Review Board for restoration of their voting rights. There was a backlog of more than 10,000 applications, and even when the board got around to reviewing an application, its decision-making process was arbitrary and opaque. Scott effectively bragged that he could issue pardons to whomever he wished, and that any oversight was an unconstitutional curtailment of his prerogative. As he himself put it, “There’s absolutely no standards, so we can make any decisions we want.”

Intentional or not, Scott’s discretionary system of rights restoration exacerbated the racist impacts of felony disenfranchisement. Scott restored the right to vote to very, very few people — between 2011 and April of 2018, just 3,000 individuals. Again, our data on race is limited to individuals who were formerly incarcerated and went on to register. Of those, less than a third (20) were black. Thirty-one of them were white.

While we’re of course dealing with a very small sample here, it is remarkable that previously incarcerated individuals who had their rights restored under Crist and registered to vote were substantially more likely to be black than under Scott.

Scott’s discretionary system also skewed the impact of rights restoration along partisan lines. Those who had their rights restored by Scott were twice as likely to register as Republicans as individuals who had their rights restored by Crist. Moreover, the process set up by Scott certainly created reason to question whether clemency decisions were made for political reasons. In one instance, Scott asked an applicant for clemency during his hearing why he had voted illegally while disenfranchised. The applicant attempted to explain himself, and then noted that he had cast the illegal ballot for Scott. Just seconds later, Scott granted his application and restored his voting rights.

None of this should come as a shock; we know that systems that depend on personal discretion are likely to further marginalize disadvantaged communities, regardless of the intent of the person making the decision.

Looking Forward

We should all be celebrating the passage of Amendment Four in Florida, but our work is far from finished. Certainly, securing the right to register to vote is an important and significant first step. But that’s what it is — a first step. Our research shows that previously incarcerated individuals in Florida who have had their rights restored register and vote at very low levels. Currently, just 14 percent of those who went to prison and have had their rights restored are registered to vote. And, in August’s primary, turnout among registered returned citizens was just three-quarters that of the statewide average.

There are a host of structural reasons why these folks might not register or cast a ballot: lack of transportation, hourly wage jobs that make taking time off to vote difficult, candidates that don’t represent their interests, and a lack of familiarity with the process. Some of these can be addressed through policies such as automatic voter registration, which make getting on the rolls in the first place easier. But truly creating a system in which our returned neighbors’ voices are heard will require much hard work. And so, while we celebrate tonight’s win in Florida, let’s steel ourselves for the work to come.