Crossposted on National Review Online

Less than a year after taking charge at the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Director James Comey has turned to the pages of the New York Times to stoke public anxiety about a “metastasized” al-Qaeda threat. Clearly, terrorism has been a good issue for the FBI, helping it obtain vastly expanding authorities and resources since the 9/11 attacks, and a thicker wall of secrecy to prevent the public from seeing how it uses them. Comey’s new fear-mongering is part of his continuing effort to transform the FBI into a full-fledged domestic intelligence agency. For anyone concerned about unchecked government power, this is a bad idea. And for anyone only concerned with effective security, it is even worse.

The FBI is the most powerful agency in the federal government, as it has the legitimate tools and authorities necessary to investigate allegations of criminal activity. As the nation’s predominant law-enforcement agency it can probe federal, state. and local government officials, members of Congress, and even the president (not to mention the rest of us). An FBI agent merely asking questions about a political candidate, a religious leader, or a community activist can start rumors that destroy reputations and alter destinies, without ever leveling charges that could be defended. The Founders recognized this threat to individual liberty and democratic governance, which is why fully half of the amendments in the Bill of Rights are designed to restrict the government’s police powers and force public accountability over their use.

By transforming itself into a domestic intelligence agency, however, the FBI slips these constitutional restraints. Intelligence agencies by their nature operate in near-impenetrable secrecy, mask their sources and methods, and collect information against people not even suspected of wrongdoing. They use deception as a primary tool and seek to disrupt the activities of those they perceive as enemies of the state, rather than prosecute them. Often their victims never know how their fortunes changed and, even if they suspect government interference, don’t have a legal means to challenge it.

The FBI has a long history of abusing its claimed intelligence authorities to impede Americans’ First Amendment rights. And a 2010 Inspector General audit revealed this inclination to view political activism as a potential threat has recently resurfaced in today’s FBI. Indeed, FBI training materials state that “the FBI has the ability to bend or suspend the law and impinge on freedoms of others” when using its intelligence authorities.

These habits and practices bleed over to corrupt the FBI’s interactions with Congress, the courts, and the public, further undermining constitutional democracy. Intelligence leaks regarding the FBI’s use of its Patriot Act authorities reveal it misled Congress during reauthorization hearings in 2005, 2009, and 2011. The FBI and other law-enforcement agencies are also using parallel construction to hide from courts how evidence is collected through legally suspect intelligence programs like Hemispheres, violating defendants’ rights to challenge government methods. Citing secret threat intelligence to justify government actions stifles the public debate necessary for effective policy making by rendering those outside the intelligence community unqualified.

The timing of Comey’s statement tells the story. Threat inflation is an old Cold War trick intelligence agencies use to quell criticism over poor performance, which the FBI recently received in two government reports documenting its lackadaisical response to Russian warnings about future Boston Marathon bomber Tamerlan Tsarnaev. A populace worried about a lurking menace isn’t likely to demand accountability for the policeman’s previous failures.

And Comey uses the traditional tactics, claiming access to secret evidence that contradicts that available in the public sphere: “I didn’t have anywhere near the appreciation I got after I came into this job just how virulent those affiliates had become,” Comey told the Times. “There are both many more than I appreciated, and they are stronger than I appreciated.”

To put the terrorism threat into perspective, Jim Harper of the Cato Institute pointed out that Americans are actually eight times more likely to be killed by a police officer than a terrorist. Stacie Borrello compared the four U.S. deaths attributable to al Qaeda-inspired terrorism in 2013 to eleven deaths caused by toddlers with guns the same year. And Brian Michael Jennings reminds us that during the 1970s the U.S. experienced 50 to 60 terrorist bombings a year, so there’s actually far less terrorism today.

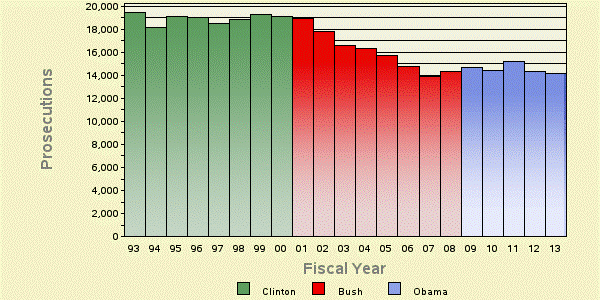

The point is not to argue there isn’t a terrorist threat. As a former FBI agent, I know better. But there are numerous threats to public safety and the FBI’s focus on terrorism intelligence collection is undermining its performance in other important areas. Though the FBI has added thousands more agents and analysts since 9/11, its criminal prosecutions have dropped significantly, according to Justice Department data provided to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse:

The financial crisis provides a case in point. In 2004, the head of the FBI’s white-collar crime program warned about a mortgage-fraud epidemic, but resources for these investigations continued to be cut in favor of counterterrorism. Then by 2009, the Director of National Intelligence called the global economic crisis the “primary near-term security concern of the United States.” Intelligence should be designed to focus government’s resources on protecting the nation from the next threat, not the last one.

Finally, there’s little evidence that the FBI’s intelligence-first approach is effective in preventing terrorism, anyway. The FBI’s most indiscriminate terrorism intelligence tool, the telephone metadata program that sweeps up information about all our calls, has never stopped a terrorist attack. And reviews of its work in failed investigations involving Tamerlan Tsarnaev, David Headley, Carlos Bledsoe, and Nidal Hasan (who all slipped through the cracks and executed deadly plots even after coming under the FBI’s scrutiny) indicate that the relentless workload created by the overwhelming amount of information the FBI collects is part of the problem, not the solution. Shielding government agencies from robust public accountability has never been a recipe for effective performance.

If the FBI were truly an “intelligence-driven organization,” as Comey likes to say, it would empirically evaluate all the threats we face, and utilize methods scientifically demonstrated to be effective to efficiently address them. It is time for Congress to conduct a thorough examination of the FBI’s use of its post-9/11 authorities to end programs that are unnecessary, ineffective, or prone to abuse. Just calling what you’re doing intelligence doesn’t make it intelligent.