In their recent McCutcheon decision (and in Citizens United before it), Chief Justice John Roberts and his conservative Supreme Court colleagues justified striking down important campaign finance laws by suggesting that robust disclosure would be enough to protect our democracy. Such disclosure is far from a reality, however.

In fact, we are moving in the wrong direction, away from transparency toward a system dominated by “dark money” — political spending whose ultimate source is shrouded in secrecy because it comes from groups not required to disclose their donors.

Less than a decade ago, transparency in political spending was the norm for federal elections. Then, in a series of decisions culminating in Citizens United, the courts vastly expanded which groups could run independent political ads. Federal disclosure laws remained virtually unchanged, however, opening up a variety of easy-to-exploit loopholes.

As a result, dark money groups who do not disclose their donors have proliferated. Many of these organizations have names like “Freedom Partners” and “Americans Elect,” which reveal almost nothing about themselves or their real agendas. In the 2012 presidential election, their spending topped $300 million, more than twice what they spent in 2010.

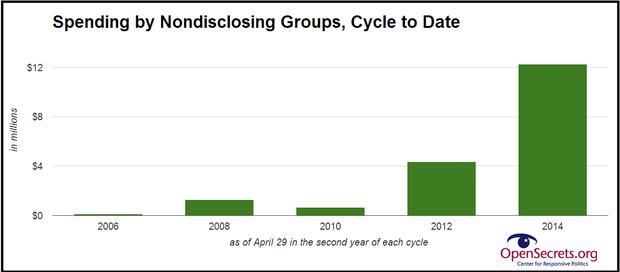

This trend toward secrecy appears to be accelerating: A report released yesterday by the Center for Responsive Politics indicates that dark money spending is nearly three times higher now than it was at the same point in 2012.

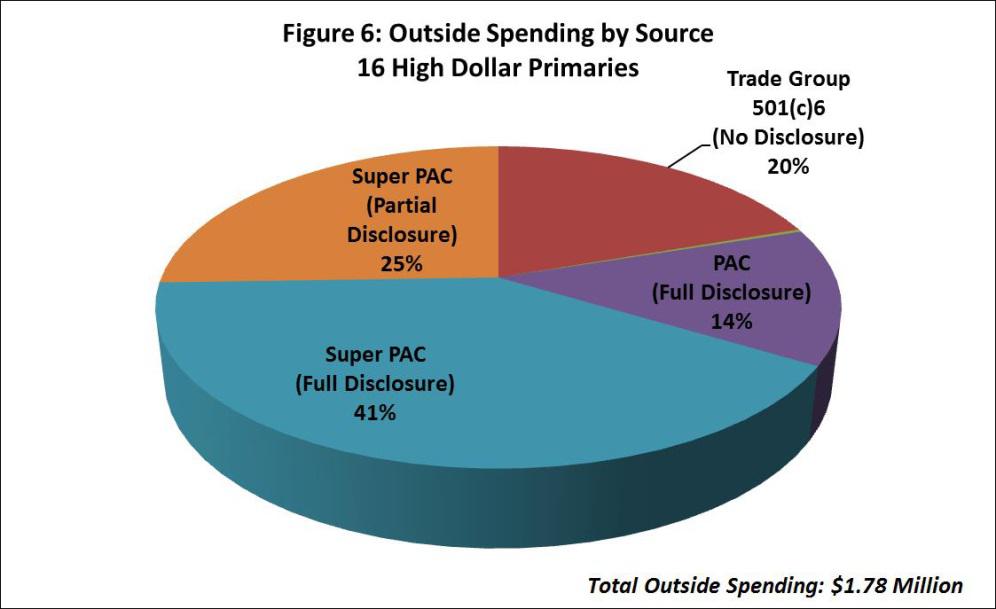

A Brennan Center study of 16 competitive congressional races, released this week, shows this trend in action: 45 percent of independent expenditures in the first quarter of this year came from groups that disclose either none or only some of their donors.

If anything, statistics like these probably understate the overall trend. After all, 2014 is not a presidential election year, so many groups likely to be active in 2016 will not bother to run ads.

The emergence of dark money is bad news for our democracy and our society. Disclosure “arm[s] the voting public with information,” Chief Justice Roberts noted in McCutcheon, allowing voters to better judge the policy alternatives before them. Disclosure also empowers shareholders to monitor how managers are spending corporate funds. And disclosure may (albeit to a lesser extent than other measures) deter actual corruption and its appearance, by shining light on who is spending large amounts of money to get whom elected.

In a system ruled by dark money, these benefits vanish. Big political spenders can literally hide from the very messages they themselves are funding. As Justice Antonin Scalia — no friend to most campaign finance laws — has noted, “[r]equiring people to stand up in public for their political acts fosters civic courage, without which democracy is doomed.” A society that campaigns anonymously,” he continued, “does not resemble the Home of the Brave.”

This rising tide of dark money ought to be a bipartisan concern. With sufficient political will, solutions are plentiful. Yesterday, for example, the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration held a hearing, through which it received many suggestions for how Congress could boost transparency. In the face of congressional inaction, the Brennan Center has also identified measures President Obama could take on his own.

Stopping the rise of dark money will not fix many of the problems the Supreme Court created when it unilaterally embarked on its quest to deregulate money in politics — but taking the Court at its word on transparency is a good first step. We should take it.

(Photo: Thinkstock)