The Road Not Taken on Gerrymandering

Congress’s failure to pass anti-gerrymandering legislation earlier this year will have adverse consequences in the midterm battle for the House.

Part of

Earlier this year, Congress had a chance to pass landmark anti-gerrymandering reforms as part of Democrats’ omnibus democracy bill, the Freedom to Vote: John R. Lewis Act, but the bill narrowly failed on the Senate floor because of the filibuster. That failure will have ripple effects in the battle for a closely divided House in 2022.

Had the legislation passed, voters around the country would have had immediate access to powerful new tools to fight partisan gerrymandering that would have let them straightforwardly block states from using severely gerrymandered maps in the 2022 midterms.

Under the John Lewis Act, voters could have asked a federal district court to analyze congressional maps for partisan bias using the results of the last two presidential and U.S. Senate elections in a state. If easy-to-use standard partisan bias metrics showed that a map was significantly skewed in favor of one party or the other in two or more of the analyzed elections, it would be presumed to be a partisan gerrymander and could not be used until — and unless — a state showed that it was not possible to draw a fairer map. If a state was unable to establish the fairness of the map before an upcoming election, the court overseeing the case would make temporary changes to the map.

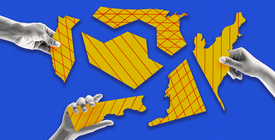

All told, congressional maps originally passed in nine states — five drawn by Republicans, three by Democrats, and one by a political appointee commission — would have required significant changes to bring them into compliance with the John Lewis Act. Subsequent state court litigation resulted in the major redrawing of Democratic-drawn maps in New York and Maryland and the Republican-drawn map in North Carolina as well as a partial fix to the map in Ohio. But even with those court-ordered changes, maps in six states, including Ohio (where Republicans simply drew a slightly less gerrymandered map), continue to have high rates of bias in favor of the party that drew them.

Congressional maps in another 13 other states, including New York’s redrawn map, had lower rates of partisan bias but also would have triggered judicial review under the John Lewis Act as possible partisan gerrymanders. Maps in these states also might have had to be redrawn under the John Lewis Act, but with lower rates of bias, the changes needed to bring them into compliance most likely would have been comparatively slight in most cases.

Given how close the contest for control of the House is in this year’s midterms, the high rates of bias under Republican-drawn maps in Florida, Georgia, Ohio, and Texas are especially eye-popping.

In 2020, Joe Biden carried 36 districts in these four battleground states, but he would have won only 30 under redrawn maps adopted by Republicans. By contrast, under John Lewis Act–compliant alternative maps proposed during the redistricting process, he would have carried between 41 and 43 districts — a striking difference of 11 to 13 seats compared to the actual maps that will be used in 2022 midterms.

The decrease in Biden districts was particularly notable in Florida, declining by four — from 12 to just 8 — even as Florida added a congressional district.

To be sure, pro-Democratic maps in Illinois and New Jersey are skewed in the other direction, containing around two more Biden districts than a John Lewis Act–compliant map would. But on balance, the skews in this decade’s maps, as they did last decade, favor Republicans, especially after the Supreme Court put a hold on lower court decisions ordering Alabama and Louisiana to create additional Black opportunity districts — districts that almost certainly would be Democratic districts. A similarly strong claim for an additional Black opportunity district is pending before a court in South Carolina. All told on net, maps that are fair from racial and partisan perspectives would contain at least 12 to 14 more Biden districts than is actually the case.

Every election invariably has its “what ifs.” For 2022, one of the biggest is shaping up to be what if Congress had overcome its dysfunction and passed legislation to tackle extreme partisan gerrymandering nationwide. It’s a lesson that should be remembered the next time there is an opportunity to reform the map-drawing process.

More from the Assessing the Redistricting Cycle series

-

Who Controlled Redistricting in Every State

While most congressional districts were drawn in partisan processes this redistricting cycle, state courts and independent commissions played a bigger role than ever. -

Anti-Gerrymandering Reforms Had Mixed Results

Redistricting reforms creating independent redistricting commissions resulted in fairer maps, while less robust reforms struggled. -

Gerrymandering Competitive Districts to Near Extinction

The House is still up for grabs, but which party gains control will be determined by races in an increasingly small number of districts.