Intelligence officials have reportedly found that Russia is interfering in the 2020 elections to try to support President Trump’s reelection, while also meddling in the Democratic primaries to help Sen. Bernie Sanders’ campaign. The reports have not revealed details about what actions Russia is taking or their scope, but my analysis of social media activity exposes some examples.

I found that social media accounts linked to the Internet Research Agency (IRA), the Kremlin-linked company behind an influence campaign that targeted the 2016 elections, have indeed already begun their digital campaign to interfere in the 2020 presidential election. And they are getting even more brazen in tactics, as a sample of new posts shows.

In September 2019, just a few months ahead of the Democratic primaries, I noticed some posts on Instagram that appeared to use the strategies and tactics very similar to those of the IRA that I observed in my research on Russian interference in the 2016 elections on social media. A few weeks later, Facebook announced that it had taken down about 75,000 posts across 50 IRA-linked accounts from Facebook (one account) and Instagram (50 accounts).

My team at Project DATA (Digital Ad Tracking & Analysis) happened to capture some of these posts on Instagram before Facebook removed them. We identified 32 accounts that exhibited the attributes of the IRA, and 31 of them were later confirmed to be the IRA-linked accounts by Graphika, a social media analysis firm commissioned by Facebook to examine the accounts.

Some strategies and tactics for election interference were the same as before. Russia’s trolls pretended to be American people, including political groups and candidates. They tried to sow division by targeting both the left and right with posts to foment outrage, fear, and hostility. Much of their activity seemed designed to discourage certain people from voting. And they focused on swing states.

But the IRA’s approach is evolving. Its trolls have gotten better at impersonating candidates and parties, more closely mimicking logos of official campaigns. They have moved away from creating their own fake advocacy groups to mimicking and appropriating the names of actual American groups. And they’ve increased their use of seemingly nonpolitical content and commercial accounts, hiding their attempts to build networks of influence.

Continuing the same strategies and tactics

Overall, the IRA appears to still employ many of the same strategies and tactics as in 2016: posing as domestic actors, the IRA targeted both sides of the ideological spectrum with wedge issues. Especially noticeable were same-side candidate attacks (i.e., an “in-kind candidate attack” targeting the likely voters of the candidate), a type of voter suppression strategy designed to break the coalition of one side or the other.

Fraudulent identity

The IRA used generic names or mimicked existing names similar to domestic political, grassroots, and community groups, as well as the candidates themselves.

Targeting both sides

We made inferences on targeting based on account names, followings, and followers because unlike our studies conducted in the 2016 elections (e.g., Kim et al., 2018), we were unable to collect information about the users who were exposed to the posts this time.

The IRA targets both sides of the ideological spectrum to sow division. This strategy is unique to Russian election campaigns, making it different than conventional persuasion-oriented propaganda or other foreign countries’ election interference strategies.

The divide between the police and the Black community, for instance, has been a running theme of the IRA’s influence campaigns, as clearly exhibited in IRA activities between 2014 and 2017 through posts around “Blue Lives Matter” vs. “Black Lives Matter.” Furthermore, the IRA exaggerated a sharp division in the African American community.

In the context of the 2020 elections, I found both endorsement and attack messages for major candidates, parties, and politicians including the president. Compared to the posts highlighting existing divides around social identities or issues, election-related endorsements and attack posts are more direct, honed, and straightforward.

Source: Instagram

Source: Instagram

Note on images: All images are from Instagram (September 2019). The posts and identified accounts were later taken down by the company for links to the Internet Research Agency. The identities of non-IRA parties including domestic political groups’ logos, the faces of ordinary citizens, and comments by non-IRA users are redacted.

Source: Instagram

Source: Instagram

Source: Instagram

Source: Instagram

Wedge issues

The majority of the IRA’s influence campaigns are indeed issue or interest based. The IRA is well-versed enough in the history and culture of our politics to exploit sharp political divisions already existing in our society. Targeting those who are likely to be interested in a particular issue but dissatisfied with the current party platforms or policies, the IRA campaigns often create an “us vs. them” discourse, feeding fear to activate or demobilize those who consider an issue personally important.

My analysis of the IRA campaigns between 2014 and 2017 found that race, American nationalism/patriotism, immigration, gun control, and LGBT issues were the top five issues most frequently discussed in the IRA’s campaigns.

Similarly, the issues frequently mentioned in the IRA’s posts in 2019 include racial identity/conflicts, anti-immigration (especially anti-Muslim), nationalism/patriotism, sectarianism, and gun rights.

Source: Instagram

Source: Instagram

Source: Instagram

Source: Instagram

Source: Instagram

Source: Instagram

Targets of those issue or interest based posts include veterans, working-class whites in rural areas, and nonwhites, especially African Americans.

One notable trend is the increase in the discussion of feminism at both ends of the spectrum.

Source: Instagram

Source: Instagram

Source: Instagram

Source: Instagram

It is also notable that one of the accounts, stop.trump2020, was fully devoted to anti-Trump messaging, similar to the IRA’s organization of the post-election rally, “Not My President.”

Geographic targeting

Geographically, these accounts specifically target battleground states including Michigan, Wisconsin, Florida, Ohio, and Arizona.

Voter suppression

Drawing upon the literature (e.g., Wang 2012), I define voter suppression as a strategy to break the coalition of the opposition. Accordingly, I identify four types of voter suppression messages: election boycott, deception (lying about time, location or manner of voting), third-party candidate promotion (e.g., the promotion of Jill Stein targeting likely Hillary Clinton voters), and same-side candidate attack (i.e., an in-kind candidate attack, such as an attack on Clinton targeting likely Clinton voters).

Among the posts we captured in September 2019, I did not notice any messages that promoted election boycotts or deceptions yet, perhaps because those types of voter suppression campaigns usually occur right before the elections, thus it was too early to observe them.

However, I found other types of voter suppression tactics, such as “third-candidate” promotion (e.g., promotion of Rep. Tulsi Gabbard) and same-side candidate attacks, both targeting likely Democratic supporters.

In particular, the same-side candidate attack tactic that centers around major candidates in the Democratic primaries is very common. For example, trolls targeted liberal feminists with attacks on former Vice President Joe Biden portraying him as engaging in inappropriate touching.

Source: Instagram

Source: Instagram

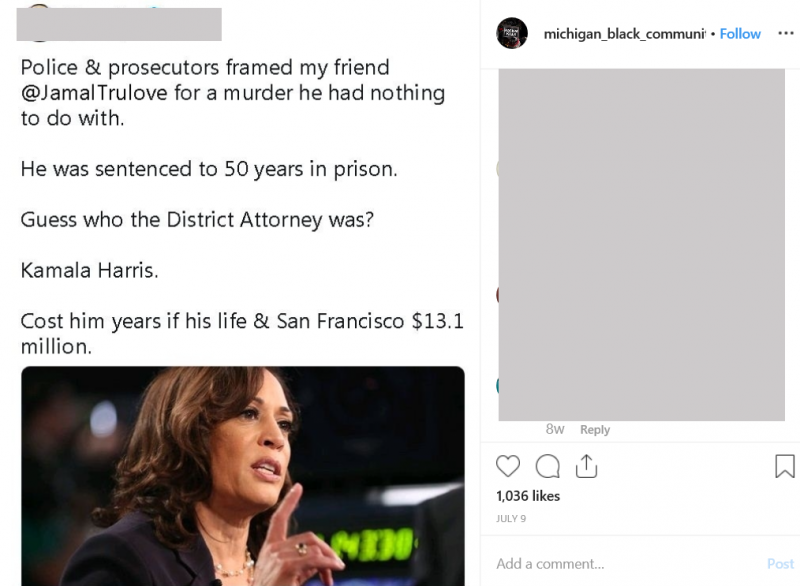

In another example, the IRA targeted African Americans for heavy attacks on Sen. Kamala Harris.

Source: Instagram

Source: Instagram

Do the IRA-linked groups prefer President Trump and Bernie Sanders?

Recent reports have indicated that Russia is interfering in the 2020 elections in support of President Trump’s reelection and Sanders’s bid for the Democratic presidential nomination.

In 2016, my analysis showed that while the IRA’s voter suppression campaigns on social media clearly targeted likely Clinton voters, especially nonwhite voters, no single voter suppression message targeted likely Trump voters.

As to whether Russia-linked groups are trying to aid Trump or Sanders over other candidates in 2020, unfortunately, this analysis itself cannot provide a definite answer yet.

Note, unlike my previous studies that examined the corpus of all of the digital campaigns exposed to a representative sample of the U.S. voting age population (87 million ads exposed to nearly 17,000 individuals who represented the U.S. voting age population) or the entire body of IRA posts on social media for three years, this analysis is limited to an anecdotal data collection at an earlier stage of the 2020 elections. While I found that similar to the 2016 case, the promotion of Trump’s agenda was prevalent across these accounts, I also found an anti-Trump account and anti-Trump messages targeting liberal voters.

In a similar vein, while I found a fake Sanders campaign account promoting Sanders, it is still premature to conclude that Russia is helping him at this point. For example, The United Muslims of America, one of the IRA groups that was active in the 2016 election, appeared to promote pro-Clinton agenda early on, but it later turned into one of the most anti-Clinton groups. More systematic analysis examining the full scope of the IRA activities around the 2020 elections are required.

However, it is very clear that as of September 2019, the IRA-linked groups have already begun a systematic campaign operation to influence the 2020 elections on Facebook and Instagram. This includes targeting liberal voters with attack messages on major candidates in such as Biden and Sen. Elizabeth Warren.

The evolution of Russian tactics

Despite tech platforms’ implementation of transparency measures, it appears that the IRA tactics aimed at the 2020 elections have become even more brazen than those from 2016.

Fraudulent identity

In 2016, the IRA created “shell groups” mimicking grassroots advocacy groups, and in some cases, impersonating candidates. Those fakes were relatively easy to detect, as an examination often revealed that those shell groups existed solely in Facebook Pages or external websites. They often used their own invented logos, landing page addresses, and the like, even when they tried to mimic existing domestic actors.

IRA attempts to influence the 2020 election appear to have improved their mimicry, however. In the newer IRA posts, I saw fake accounts pretend to be a Democratic candidate or an official campaign committee, with only subtle changes in the names or landing page addresses that are harder to notice. For example, the IRA mimicked the official account of the Bernie Sanders campaign, “bernie2020,” by using similar names like “bernie.2020__”.

Use of domestic nonprofits’ identities

Among the IRA posts I reviewed that touched on the 2020 election, many use the identity of legitimate, relatively popular nonprofits, political action committees (PACs), or grassroots organizations, even in their original posts (not a repost from those groups).

Because I did not cross-compare all of the IRA’s posts and those of domestic groups historically, at this point, it is unclear whether the IRA is simply stealing names, logos, and materials already used by legitimate organizations, or unwitting collaboration between those legitimate organizations and the IRA’s shell groups occurred.

However, it is worth noting that in 2016, even when the tech platforms were not imposing transparency measures, the IRA never used exactly the same logo or name of already existing, legitimate, and active domestic groups while they mimicked the groups’ activities.

Tech platforms’ policies against political campaigns by foreign actors (e.g., Facebook Pages need to verify their U.S.-based identity) might have made Russian operations adapt to the changes and evolve over time. By using domestic political groups’ identities and materials, it would have been easier for foreign actors to bypass tech platforms’ enforcement. The lack of severe punishment for the 2016 election interference also might have reinforced such illicit behavior.

This tactic works favorably overall for IRA election interference strategies that exploit existing sharp political divides in our society, as it boosts the credibility of messages and helps amplify them among the members and supporters of the domestic groups. However, it certainly poses a great many challenges to investigators as well as tech platforms, as it is extremely difficult to detect “foreign” election interference and coordination.

Use of nonpolitical, commercial, domestic accounts and materials

Similarly, I noticed an apparent increase in the use of nonpolitical content and seemingly apolitical or commercial materials. While this tactic was utilized in 2016, especially to build audiences and support bases at an earlier stage of the IRA’s influence campaigns, it was not as common as now. This tactic conceals the political nature of the large scope of influence campaigns and its coordinated networks, disguising the true purpose of the campaigns.

What should we do?

The potential adaptation and evolution of the foreign election interference tactics pose even more challenges to those who care to protect our citizens and election systems. Ahead of the 2020 elections, digital political advertising has become a hot potato. Twitter withdrew from selling political advertising altogether, and Google decided to limit microtargeting options for candidate campaigns’ narrow-targeting ability. Facebook has announced no major change in political ad policies, although it has made its transparency tools easier to use.

These recent developments have made some at both ends of the political spectrum unhappy. Yet no laws have been enacted to promote election integrity on digital platforms. Three years after Russia’s interference in the 2016 elections came to light, we are still debating what we should do to prevent malicious actors’ disinformation campaigns from targeting our elections — especially sweeping, systematic foreign election interference campaigns on digital platforms used by ordinary people in their daily lives.

A comprehensive digital campaign policy framework must be considered to ensure the integrity of election campaigns. Just ahead of the elections, unfortunately, no such regulatory policy exists.

Enhance transparency and monitoring mechanisms

Tech platforms must do a better job at transparency, including identity verification and labeling. This would help reduce foreign actors’ production of “shell groups.”

It’s still too hard to discern foreign and domestic actors, false identities, and potential coordination between various groups, especially because of the tactics discovered in this analysis, such as the use of domestic groups’ logos and identities in the original posts. Platforms like Facebook aggressively protect intellectual property, for example with technology that automatically blocks posts that contain copyrighted material like songs. The platforms should consider applying similar tools to the political arena to block fake accounts from stealing the logos and brand identity of candidates and groups.

Enhance the Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA)

The law requires that agents representing the interest of foreign powers in a political or “quasi-political” capacity must disclose their relationship with the foreign power. While FARA focuses on lobbying activities, it should acknowledge the changes in the nature of foreign influences in the digital era. Stronger regulation under FARA, including enhanced monitoring mechanisms, could help.

Enact rules for digital political campaigns

While the Federal Election Commission provides the rules and policies for political committees, its current policies do not adequately address digital political campaigns in general. For instance, a clear and consistent definition of political advertising must be provided across tech platforms to make transparency measures more effective. Likewise, comprehensive, cross-platform archives of political campaigns, including issue ads and target information, would help audiences, law enforcement, and researchers understand what’s happening in digital political advertising.

Without safeguards like these, Russia and other foreign governments will continue their efforts to manipulate American elections and undermine our democracy.

Young Mie Kim is a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a Brennan Center for Justice affiliated scholar.