Gerrymandering Explained

The practice has long been a thorn in the side of American democracy, but it’s becoming a bigger threat than ever.

Part of

Every 10 years, after the census, states redraw the boundaries of congressional and state legislative districts to reflect population changes, a process known as redistricting. Done well, it’s a chance to create maps that elect legislative bodies that fairly represent communities and that are, in the words of John Adams in 1776, an “exact portrait, a miniature” of the people as a whole. Redistricting also takes place at the local level to redraw the boundaries of districts used to elect the members of bodies such county commissions, city councils, and school boards.

But redistricting also is a chance for those in control of the process to rig maps to favor certain candidates or political parties, a practice known as partisan gerrymandering.

Although gerrymandering has long been a problem in the United States, the redistricting cycle after the 2020 census was the first since the Supreme Court’s 2019 ruling that gerrymandered maps can’t be challenged in federal court. Since then, Americans have seen gerrymandering ramped up to unprecedented levels in many places — and the worst may be yet to come.

Four takeaways on how voting maps made the difference in the tight fight for the House in 2024. >>

Here’s what to know about partisan gerrymandering and how it impacts our democracy.

Partisan gerrymandering is undemocratic.

Elections are supposed to produce results that reflect the preferences of voters. But when maps are gerrymandered, politicians and the powerful choose voters instead of voters choosing politicians. The result is skewed, unrepresentative maps where electoral outcomes are virtually guaranteed, even when voters’ preferences at the polls shift dramatically. In extreme cases, the party drawing the maps may even be able to win a majority of seats even though it wins only a minority of the vote.

These line drawing abuses are especially frequent when one political party has sole control of the process. Under single-party control, map drawing tends to occur with inadequate transparency, with partisan concerns taking priority over the fair representation of the public as a whole.

There are multiple ways to gerrymander.

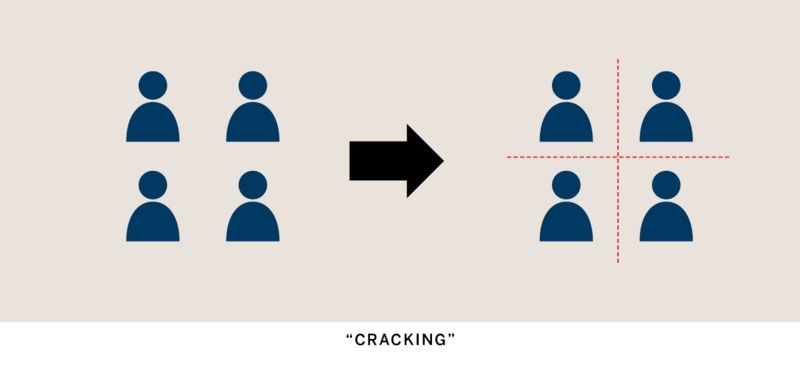

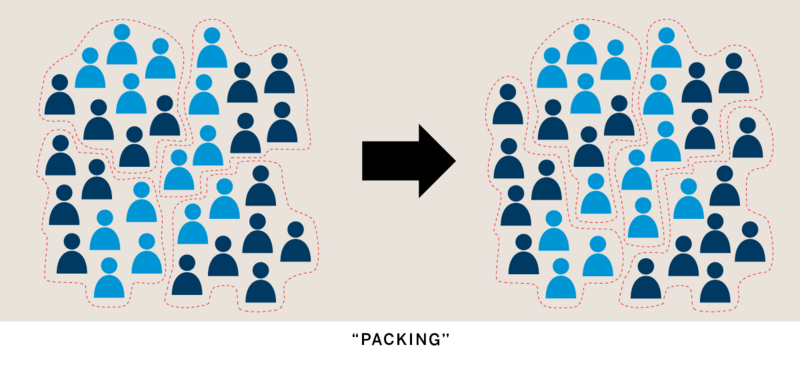

The easiest way to understand gerrymandering is through the lens of two basic techniques: cracking and packing.

Cracking splits groups of disfavored voters among multiple districts. With their electoral strength divided, cracked groups struggle to elect their preferred candidates in any of the districts because they are too small a share of the electorate to be effective.

Packing is the opposite of cracking. With packing, map drawers cram members of disfavored groups or parties into as few districts as possible. The packed groups are able to elect their preferred candidates by overwhelming margins, but their voting strength is weakened everywhere else.

These techniques are not mutually exclusive — both may be deployed by map drawers to engineer a decided partisan advantage.

Don’t judge a district by its shape.

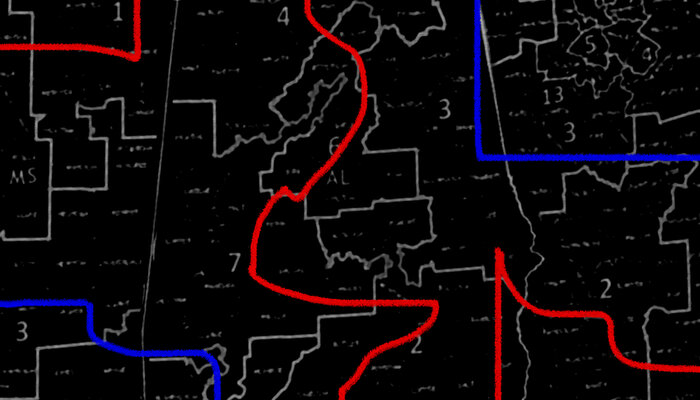

While gerrymandering sometimes results in oddly shaped districts, that isn’t always the case. A smart gerrymanderer can create cracked and packed districts that look neat and square but nonetheless skew heavily in favor of one party. North Carolina’s current congressional map is a case in point. Although the districts lines might look normal, they sort voters with such careful precision that Republicans are virtually assured of winning 10 of the state’s 14 congressional races and could win as many as 11 — a wildly skewed result for a perennial battleground state that regularly elects Democrats to statewide offices.

Conversely, odd-looking districts may be so shaped simply because they follow a geographic feature such as a river or city boundaries or because they keep together communities that have common identities or important shared representational needs.

Gerrymandering impacts the balance of power.

Current congressional maps show the power of gerrymandering.

After the 2020 census, Republicans controlled the redistricting process in more states than Democrats, and used this advantage aggressively. By Brennan Center estimates, maps used in the 2024 election had on average a net 16 fewer Democratic or Democratic-leaning districts than maps than complied with the strong anti-gerrymandering standards in the stalled federal Freedom to Vote Act.

Maps in Texas and Florida are especially skewed, but North Carolina provides one of the most striking examples of the power of gerrymandering to affect the balance of power, not only in a state but nationally. After the North Carolina Supreme Court struck down the state’s 2021 congressional map as an impermissible partisan gerrymander under the state constitution, the court put in place a map drawn by court-appointed experts. Using that map in the 2022 midterms, the state sent an even number of Democrats and Republicans to the U.S. House, a result in well in keeping with the Tar Heel State’s battleground politics.

But then, after changes to the composition of the state supreme court, the court reversed its recent ruling and said it would no longer police partisan gerrymandering. Free to gerrymander, the Republican-controlled legislature redrew the map, and after the 2024 election, North Carolina saw three Democratic districts flip to Republicans, enough to give control of the U.S. House to the GOP by a slim margin. Another Democratic district narrowly avoided flipping.

To be sure, Republicans weren’t alone in gerrymandering. Democrats in Illinois, for example, boldly redrew their state’s congressional map to reduce Republicans to holding just 3 of 17 seats, the fewest number of Republican seats since the Civil War. By contrast, the Brennan Center estimates that a fair Illinois map would have around 6 GOP seats.

The problem of gerrymandering is getting worse.

Gerrymandering is not new. Even the founding generation, for all its lofty democratic ideals, was not above putting a thumb on the scale. Elbridge Gerry, for whom the practice of gerrymandering is named, was both a signer of the Declaration of Independence and a member of the Constitutional Convention. And in designing Virginia’s very first congressional map, Patrick Henry famously attempted to draw district boundaries that would block his rival, James Madison, from winning a seat.

However, while gerrymandering dates back to the earliest days of the nation, it has also changed dramatically since the founding. Today, intricate computer algorithms and detailed data about voters’ political preferences and behavior allow map drawers to draw districts with surgical precision. Where gerrymanderers once had to pick from a few maps drawn by hand, they can now create and pick from thousands of computer-generated options.

Add to that a harsh new reality: Map drawers in most of the country no longer have to fear judicial intervention. In the 2019 case Rucho v. Common Cause, the Supreme Court held that while gerrymandering was “inconsistent with democratic principles,” gerrymandering claims were a “political question” beyond the reach of federal courts to address. This follows an earlier Supreme Court case, LULAC v. Perry, which greenlighted the practice of mid-decade redistricting for partisan purposes.

Gerrymandering affects all Americans, but some of its most significant costs are borne by communities of color.

Targeting the political power of minority communities is often a key element of partisan gerrymandering. This is especially the case in the South, where white Democrats are a comparatively small part of the electorate and often live — problematically from the standpoint of gerrymander-minded map drawer — in the same neighborhoods and communities as white Republicans. Even with computer-assisted slicing and dicing, it can be hard to put together a map that has the desired partisan effect simply by targeting white voters.

By contrast, continued residential segregation and racially polarized voting patterns, especially in southern states, mean that cracking or packing communities of color can be an efficient if cynical tool for creating advantages for the party in control of the map-drawing pen. This is true regardless of whether it is Democrats or Republicans drawing the maps.

Here again, the Supreme Court has made things worse. The Constitution and the Voting Rights Act prohibit racial discrimination in redistricting. But because there often is correlation between party preference and race, especially in the South, the Court’s ruling in Rucho opened the door for states to simply defend racially discriminatory maps on grounds that they were lawfully discriminating against Democrats rather than impermissibly discriminating against Black, Latino, or Asian voters.

South Carolina offers a vivid example of this dynamic. After the 2020 census, state legislators there redrew the coastal district of Republican congresswoman Nancy Mace to remove large numbers of Charleston-area Black voters. When Black voters challenged the reconfigured district in federal court as an unconstitutional racial gerrymander, lawmakers defended the map based on politics — namely, the desire to make Mace’s highly competitive district more reliably Republican. Targeting Black voters and their political power was just a means to an end. The Supreme Court agreed, finding that Black voters hadn’t proven that the map’s lines were based on race and not party affiliation.

South Carolina is far from alone. In states and localities around the country, naked partisanship is increasingly being used as an excuse for maps that dilute the voting power of the nation’s fast-growing communities of color.

Congress can outlaw partisan gerrymandering.

Even though the Supreme Court has been unwilling to constrain these antidemocratic abuses, Congress still can.

In 2022, the House passed the Freedom to Vote Act, a landmark piece of federal democracy reform legislation that would have prohibited mid-decade redistricting and banned partisan gerrymandering in congressional map drawing. It also would have improved legal protections for voters of color in redistricting, required greater transparency in the map-drawing process, and improved voters’ ability to challenge gerrymandered maps in court and win timely relief. However, while the bill had enough votes to pass in the Senate, it failed because the body fell two votes short of changing filibuster rules to allow a floor vote.

The vote split along party lines, with every Democrat in support and every Republican opposing. But with the Supreme Court having enabled a new round of aggressive mid-decade gerrymandering, and both parties seemingly eager to join in, that could change in time, with both Republicans and Democrats coming to see the benefits of having uniform national standards and a level playing field. Fair representation for all Americans depends on it.

More from the Explainers collection

-

The President’s Executive Order on Elections

The illegal order risks preventing millions of eligible American citizens from voting. -

The Voting Rights Act, Explained

The landmark 1965 law is one of the most successful civil rights measures in history, but the Supreme Court has eviscerated it. -

The Filibuster Explained

The procedure, whose use has increased dramatically in recent decades, has troubling implications for democracy.