Introduction

Legislatures are an indispensable element of American democracy, including—and perhaps especially—during times of crisis. Yet with the Covid-19 pandemic approaching its third month in the United States, 13 state legislatures are currently adjourned, suspended, or postponed as a result of the virus, while another 16 have already adjourned without any announced plans to meet again, and four have not gathered at all this year.1 These states represent 57 percent of the population and include many of the hardest hit like New York, Georgia, and Florida. Congress met only sporadically until early May, when the Senate went back into session despite concerns about health risks for senators and staff.2

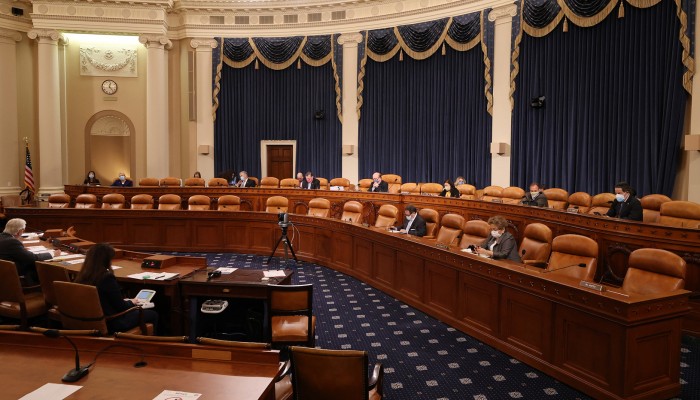

Across the country, legislatures are straining to carry out their essential functions, scarcely able to reconcile their customary ways of doing business with sensible health precautions. Recently, the Arkansas House of Representatives met in a 5,600-person basketball arena in order to allow members to maintain a safe distance from one another.3 When the Michigan legislature met in person in early April, it followed elaborate procedures, with legislators wearing masks, taking turns entering the chamber, and standing far apart.4 Likewise, in the U.S. House of Representatives last month, a vote on Covid-19 relief legislation—which would have taken 20 minutes under normal circumstances—was spaced out over an hour and a half, and members were assigned a time to vote based on their last names. Then the House took a 30-minute break for cleaning.5

Some legislative bodies are adapting with creative solutions in response to the pandemic. The Utah state legislature, for example, met virtually in mid-April. Despite now-familiar glitches, inadvertently muted mics, and one senator’s cat meowing during the meeting, the session was considered a success logistically.6 Legislatures in other countries are also moving in this direction. The British Parliament met virtually for the first time on April 22, as did the Canadian Parliament on April 28.7 The U.S. House of Representatives recently approved procedural changes to help mitigate the health risks from more than 400 people gathering in a small space. The House’s emergency procedures temporarily allow a member absent from the Capitol to authorize another member to cast their vote by proxy and also permit remote committee hearings.8 Some members of the Senate have also pressed for remote operations, but to no avail so far.9 Other U.S. bodies have adjusted longstanding legislative rules and procedures, such as allowing more proxy voting or modifying quorum requirements that govern how many members must be present to conduct business.10

The push to adopt emergency procedures is a response to legitimate dangers. As of this writing, seven members of Congress have already tested positive for the novel coronavirus.11 At least three state legislators—Michigan representative Isaac Robinson, Louisiana representative Reggie Bagala, and South Dakota representative Bob Glanzer—have died of coronavirus related complications, and dozens more have tested positive or exhibited symptoms.12

In the face of an evolving public health emergency, however, many of the United States’ legislative bodies are still holding only hurried or perfunctory legislative sessions. And they often are using ad hoc procedures that do not promote robust deliberation or engaged policymaking.

We need a better approach—one that will allow legislatures to help manage the Covid-19 pandemic and attend to other critical business while taking appropriate steps to protect the health and safety of members, staff, and the many other people who interact with them.

Part I of this paper discusses why it is vital for legislatures to remain fully engaged during crises like Covid-19. Congress and state legislatures perform different roles in our constitutional system and have very different sets of traditions and legal constraints. But during times of adversity, our system of government depends on elected representatives at both levels to remain fully engaged in the people’s business. Congress and state legislatures are both responsible for critical functions that include appropriations, ensuring (in different ways) the continuation of essential government functions and pandemic responses, oversight over their respective executive branches, and advancing other critical legislative priorities.

Part II lays out principles for how to alter key legislative procedures and rules to allow for continued operations consistent with public safety and core democratic values. First, Congress and state legislatures should rapidly begin transitioning to virtual meetings, making them as similar as possible to in-person meetings. Second, quorum rules should be altered sparingly, and only in ways that avoid compromising a body’s core representative character. Third, legislatures should make every effort to preserve requirements for clearly recording legislators’ votes and keeping them publicly accountable for their decisions, including ensuring transparent vote tabulation and strictly limiting proxy voting. Fourth, legislatures should exercise extreme caution before giving greater agenda-setting or procedural power to a select subset of their membership. Finally, legislatures should give full effect to longstanding transparency and openness principles, taking advantage of expanded technological capabilities. Now more than ever, legislatures owe their constituencies a heightened commitment to open, accountable government.

Ultimately, any emergency plans crafted during this period should be guided by two overarching considerations. First, any changes should hew as closely as possible to longstanding rules and procedures. In other words, virtual meetings and other temporary changes should be designed to replicate current practice as much as possible. Second, all changes should be temporary. This is not the time to permanently alter established procedures. Measures should be narrowly fashioned to allow elected representatives to remain fully engaged in the people’s business and should lapse as soon as it is possible to return to regular order.

I. Legislatures in Times of Crisis

The U.S. government cannot function without legislatures. Indeed, at the federal level, Congress was envisioned to be the preeminent branch of government. “In republican government,” James Madison wrote in Federalist No. 51, “the legislative authority necessarily predominates.”13 Congress alone has the power of the purse, the power to write legislation, and the power to declare war, among other powers.14 The framers expected Congress to play an active role in day-to-day governance.15 While institutional arrangements vary to some degree across the states,every state legislature also plays a central role in setting policy and overseeing essential government functions.16

Of course, chief executives—the president and state governors—also play a critical leadership role, especially during emergencies. But their powers can easily be abused and must be balanced by legislative oversight and cooperation.17 At the state level, where many of the decisions that have the most direct impact on daily life during the pandemic are taking place, governors often lack the authority to ensure that essential government functions are carried out without legislative assent.18

Moreover, whatever action government takes during a crisis, legislative participation is critical to ensuring public legitimacy. For all their individual flaws, legislatures remain among the most important fora for public debate and are the ultimate vehicle for the expression of popular opinion in a deliberative democracy.19

Historically, Congress and state legislatures have continued to operate during times of crisis and have actively participated in managing the fallout. The most obvious parallel to the present situation is the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918–19. During that period, when the United States was also embroiled in World War I, Congress and state legislatures continued to meet and pass laws, including measures to help manage the pandemic.20

Congress also continued to meet and pass legislation throughout the course of the Civil War, even when fighting came near Washington, DC.21 During the Cold War, Congress and most state legislatures enacted continuity plans to allow them to remain operational in the event of a nuclear attack.22 Both chambers also remained in session following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks even though the U.S. Capitol had been one of the intended targets. Even after deadly anthrax powder was mailed to House and Senate offices in October 2001, only the House adjourned, and only for one week.23 State legislatures also routinely stay in session to help manage serious natural disasters like hurricanes, earthquakes, and wildfires.24

As before, continuity of legislative operations during the Covid-19 pandemic remains critical. From providing funds to mitigate the economic impact of social distancing to modifying voting rules so that the 2020 election can be conducted safely, Congress and state legislatures have essential roles to play. There are four areas that are especially likely to require legislators to remain engaged on an ongoing basis.

Appropriations. At both the federal and state levels, appropriations are typically within the unique purview of the legislature (the so-called “power of the purse”).25 Legislative action is also almost always required to raise taxes or other sources of revenue. This has been Congress’s most prominent role in the Covid-19 crisis to date, which was focused initially on providing emergency funds for public health but has now transitioned to managing the pandemic’s broader effects, including its massive economic fallout.26 Legislatures in the hardest hit states are also working on supplemental appropriations to manage the pandemic and its consequences.27 Because most states are required to balance their budgets, legislatures also are finding themselves forced to make painful cuts to offset the pandemic’s economic repercussions in terms of lost tax, tourist, and other sources of revenue.28

The work of finding money to respond to Covid-19 and manage the pandemic’s broader impacts will continue for some time. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has noted that “it’s very difficult to predict [when the United States will start to get out of the worst of the pandemic],” while the International Monetary Fund has warned that economic uncertainty is “exceptionally high and is much higher than in past outbreaks.”29 Congress and state legislatures will continue to have an indispensable role to play allocating resources even as circumstances evolve.

Continuing Essential Government Functions and Pandemic Responses. Legislative action also will be needed to ensure the continuation of essential government functions and to respond to the pandemic. At a federal level, apart from appropriating funds, Congress has already taken steps that include expanding telemedicine services for Medicare patients, providing paid sick and family leave, suspending student loan payments, and creating protections against foreclosures and evictions.30

At the state level, governors and other state executive officers generally have assumed primary responsibility for day-to-day management of the crisis, but certain essential actions nevertheless fall within the legislature’s primary purview. For example, a number of state legislatures have passed laws to help manage the direct consequences of the pandemic, including by expanding the availability of paid sick leave, permitting public schools to use nontraditional instruction methods, and modifying state open government laws to allow other public bodies to meet remotely.31 Others have taken action to manage the broader economic fallout, like expanding eligibility for unemployment benefits and suspending evictions and foreclosures.32

One area where continued legislative engagement will be especially important is ensuring free and fair elections that allow all Americans to safely participate. That will necessitate measures that include expanded online voter registration, significantly expanded vote-by-mail options, and the extension of deadlines for counting and certifying election results.33 These are often changes that must be made by state legislatures, several of which have already moved to expand voting by mail.34 Many other bodies will need to act to ensure that residents of their states can vote in upcoming primaries and the general election without risk to their health.35 (In addition to action from state legislatures, there is also an urgent need for Congress to appropriate supplemental funds to help states implement new election procedures, which the Brennan Center has estimated will cost at least $4 billion.)36

Oversight. Legislatures exercise critical oversight over the executive branch.37 As early as 1792, Congress has used its oversight powers during times of crisis to root out corruption (the risk of which tends to go up with increased government spending) and address other crisis-related problems—from inadequate housing for World War II-era defense workers to a lack of information sharing among government agencies in connection to the 9/11 attacks.38

The need for congressional oversight during the current pandemic is clear. More than $2 trillion has already been appropriated to prop up the U.S. economy. As Neil Barofsky, the former inspector general for the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), recently noted, “[w]e need to ensure that this government aid is not being stolen, wasted or given to political cronies. And we need to make sure that the public is aware of how and to whom those trillions are distributed.”39 Moves by the Trump Administration to compromise independent oversight within the executive branch, including firing the longtime inspector general who was slated to oversee the pandemic bailout and three other IGs, make it even more imperative for Congress to continue to play an active role.40

Many state legislatures will also need to play an active oversight role. In hard-hit states like New York, California, and Michigan, governors have been granted broad authority, including control over billions of dollars in relief funds.41 In other states like Oregon, the governor is allowed to use general state funds “regardless of the legislatively expressed purpose of the appropriation” in a declared emergency.42 As at the federal level, active legislative oversight is an important check to ensure that states spend funds wisely and that governors and other executive branch officials do not abuse their power.

Other medium and long-term governance. Finally, it will be critical in the coming months for legislatures to take up important matters unrelated to the pandemic. While social distancing and improved medical care will hopefully continue to mitigate the worst effects of Covid-19, a vaccine is not expected until mid-2021 at the earliest.43 It is neither preferable nor feasible for legislatures to put off urgent priorities for that span of time. These priorities include annual budgets and other critical pieces of legislation to ensure the continued operation of government. During this time, legislatures should focus on how they can continue their work while safeguarding the health of members and staff and protecting the public’s right to know about and participate in decisions that will impact their lives.

II. Recommendations

Given the importance of ongoing legislative and representative governance in the midst of the pandemic, it is critical that Congress and every state legislature put emergency plans in place to establish how they will function if, as some have predicted, the Covid-19 pandemic continues to affect us in unpredictable ways for the next 18 months.44 In this section, we discuss some best practices and principles that should guide federal and state legislatures trying to craft continuity of government plans.

Many states and the federal government are currently debating new contingency plans. Unfortunately, most of them cannot turn to previous work on continuity of government, the majority of which was devised in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and therefore contemplates a very different type of emergency.45 Undoubtedly, new emergency plans adapted to Covid-19 will be unable to cover every possible twist in the coming months. As legislatures reconstitute themselves and devise new operating plans on the fly, there almost certainly will be technical glitches, frustrating missteps, and missed opportunities. The situation calls for creativity and flexibility.

At the same time, there are risks associated with poorly conceived emergency plans of operation. Legislative procedures and pathways in the United States are based on centuries of consideration about how a representative democracy works, about minority rights, and about due process and fair debate.46 As the renowned congressional procedure scholar Walter Oleszek has noted, legislative rules “provide stability, legitimize decisions, divide responsibilities, protect minority rights, reduce conflict, and distribute power.”47

Misguided rules that do not respect these democratic norms and practices can severely undermine a legislature’s basic legitimacy. When Thomas Jefferson first pondered how he would oversee the conduct the Senate while he presided over it as vice president from 1797 to 1801, he emphasized procedures that would restrict the “the wantonness of power.” He emphasized the need for rules “not subject to the caprice of the Speaker or captiousness of the members. It is very material that order, decency, and regularity be preserved in a dignified public body.”48 Since Jefferson wrote his Manual of Parliamentary Practice more than two centuries ago, legislative procedure has evolved as the party system took hold, American democracy has expanded, and the nation’s society and economy grew vastly. But core questions about whether the legislature operates in a democratic and fair way have not changed: is the legislative body representative, is it accountable to the people, and does it provides a fair and equal forum where conflict can be resolved?49

To be sure, legislative organization and procedure reflects more than just high-minded concerns.50 Legislative rules most decidedly can affect substantive outcomes, reinforce unfair power structures, or unduly aggrandize the power of individual leaders.51 But this is precisely why rule changes must be closely examined and judged based on first principles.

The types of emergency rules a legislature can implement vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. For example, when the Michigan legislature met in person on April 7, notwithstanding the death of one of its members from Covid-19, it did so ostensibly because a provision of the state’s constitution was read to bar virtual meetings.52 Other state constitutions contain no such requirement.53 More broadly, constitutions often include other types of procedural constraints, such as the U.S. Constitution’s quorum provision requiring a majority of each chamber’s members for the conduct of business.54 Because of these variations, some jurisdictions may not be able to fully implement every recommendation outlined below.

Our recommendations are as follows, divided into two broad categories: meeting and legislating, and transparency and openness. As noted, all of these recommendations are guided by the imperative to hew as closely as possible to normal procedures. The changes we do recommend should be temporary and left in place only for as long as public health experts believe they are needed to protect the health or safety of members, staff, and the public. Regular order should be restored as soon as it is feasible to do so, possibly using extra protections, such as wearing masks or sitting farther apart.55

A. Meeting and Legislating

The core challenge arising during the Covid-19 pandemic is how to meet and conduct legislative business when it may be impossible or dangerous for legislators and staff to be physically present in the same space. To address this problem, we recommend that legislative bodies consider moving to remote meetings where permitted on a temporary basis, as several have already done.56 Legislators should avoid changing other rules to accommodate that move unless absolutely necessary.

Switch to virtual sessions temporarily. One of the most critical changes any legislative body can make in response to the Covid-19 pandemic is to enable virtual meetings and hearings and remote votes. Unlike in many past crises, virtual meetings and remote voting are now feasible from both a technological and security standpoint.57 Nevertheless, in ordinary times they remain suboptimal. Writing about Congress, the scholars Timothy LaPira and James Wallner have noted that “[a] Congress whose members meet virtually and vote remotely is likely more dysfunctional and less legitimate than one whose members are physically present.”58 In the present circumstances, however, the options are regular virtual sessions, sporadic and quickfire in-person sessions with elaborate and cumbersome safety procedures, regular in-person sessions that pose serious health and safety risks, and not meeting at all. In this context, virtual sessions are vastly preferable on a temporary basis.

Legislative bodies should make every reasonable effort to hold virtual meetings that are as similar as possible to in-person meetings.59 For instance, during emergencies, it may be tempting to make the legislating process quicker or more “efficient.” For some, that might prompt new limits on the amount of time or number of times a member can speak, or on the number of bills a member can introduce.60 But such limits risk muzzling honest debate and dissent—a core feature of democratic legislatures. While some debates over emergency legislation may require special rules, such sweeping departures from regular order should be avoided.

Virtual sessions are also likely to encounter technical difficulties. As frustrating as they may be, it is imperative that they be solved and not ignored, especially during a period of democratic stress.61 Legislative business should not move forward any time a significant number of members cannot participate due to technical problems.62

When deciding whether to move to virtual sessions, most legislative bodies, including Congress, may confront different constitutional or internal procedural rules governing full legislative and committee meetings. Virtual committee meetings may be easier to conduct and raise fewer constitutional or legal questions; legislatures should explore that option with alacrity. Committees are where most of the process of legislating actually takes place, and they are also ground zero for oversight. Even if full legislative sessions must be conducted wholly or partly in person, legislatures should take advantage of the greater flexibility they are likely to have with respect to committee meetings.

Modify quorum rules sparingly, and only in ways that respect core representative principles. In a pandemic or other emergency that may pose the risk of mass incapacitation where a significant number of members are unavailable, legislative bodies may need to modify the requirements for a quorum to allow for conducting business with fewer members present. However, quorum rules should be modified with extreme care and only in ways that respect basic principles of representative democracy.

Quorum rules ensure the presence of a sufficient portion of legislators to preserve a body’s representative character. In essence, a quorum prevents undemocratic action taken by a minority.63 The American framers believed quorum requirements were sufficiently important to write them into the Constitution, mandating that both the House and Senate must have a majority of members present in order to do business.64 Like Congress, most state legislatures require a majority of elected members to be present for quorum.65 However, many state emergency laws and procedures suspend or rework quorum requirements.66 Doing so may be an invitation to rule by a small minority overseen by whoever happens to be the leaders of the two chambers at the time. This could threaten a body’s basic representative character.

Nevertheless, when dealing with continuity of government in an emergency, a legislature needs to consider the possibility of mass incapacitation of its membership, particularly in the event of a rapid attack or natural disaster (or if legislators cannot be in the same physical space and remote sessions are not permitted). Under such a circumstance, quorum rules may need to change, but legislators should take care to preserve core safeguards. One example of appropriate caution involves the rule changes passed in Oregon, which waived its legislative quorum requirement in the event of a mass incapacitation and counterbalanced it with a supermajority rule that a three-fifths majority of those able to attend would have to vote for any legislation in order for it to be enacted.67 This deals with the practical difficulties created when large numbers of incapacitated members drive down the representative core of the legislature by requiring a supermajority for enacting a law.

Modifying quorum rules may be especially pertinent in states with constitutions that require the legislature to meet in person to pass laws. However, there are often creative solutions that may be preferable to more radical changes. For example, it may be possible to conduct a blended live-plus-virtual meeting, in which a small number of members meet in person while others attend virtually and are recognized for quorum purposes.68 As long as all members have an equal right and ability to attend (virtually or in person) and the rules are not otherwise altered, these arrangements are preferable to altering quorum requirements.69

Continue tabulating individual votes. Even as legislatures move to remote sessions, they should continue to tabulate individual legislators’ votes as they ordinarily would. In the rush to enact laws while dealing with public health concerns, several states have been tempted either to suspend recorded votes or even to presume how a member votes (for example, by treating a failure to vote “no” as an affirmative vote).70 These actions, however well-intentioned, undermine democratic accountability and should be avoided. Recorded votes on important legislation require representatives to take a clear position, for which their constituents can hold them accountable. Especially given other changes already in place like virtual meetings and modified quorum requirements, an emergency is not an adequate justification for doing away with such an important component of the representative process.

Use proxy voting only when necessary and with clear limits. It may be necessary in some circumstances to permit voting by proxy. In general, proxies are discouraged for the same reason that individual vote tallies are preferred. Under normal circumstances, lawmakers are expected to show up, take part in debate, and then cast their votes in person so that there is no doubt of their accountability for each vote.71

States that are able to establish a coherent virtual legislation system should not permit proxy voting. But as noted, several states are constrained by constitutional provisions that appear to bar virtual meetings. In those limited instances—or if moving to a full virtual session is simply not politically feasible—some form of proxy voting may be needed on a temporary basis.

In the rare circumstances when proxy voting is necessary, proxy rules should be tightly crafted to ensure that votes are clearly recorded for each legislator and to prevent using the proxy system as a way to hand over votes en masse. For example, in some cases, proxy voting rules have allowed legislators to authorize a designee to vote as he or she “sees fit.”72 This undifferentiated proxy vote authorization should not be permitted. The better approach is the one taken by the Arkansas House of Representatives, whose Covid-19 emergency procedures require legislators to indicate specific proxy votes in writing ahead of time. The emergency rules recently adopted by the U.S. House of Representatives contain a similar requirement.73

Avoid delegating additional power to legislative leaders. Some legislatures have crafted new or emergency procedures granting legislative leadership significant new power to set priorities and alter procedures during the crisis.74 Such changes that concentrate legislative power among a small number of members serving in leadership should be avoided or minimized.

In most states, and certainly in Congress, legislative leaders already have significant agenda-setting and procedural authority.75 That power is often necessary, but it can also be used to cut off consideration of important issues a leader personally disfavors. For instance, in recent weeks, both federal and state legislative leaders have received criticism for attempting to limit consideration of certain relief legislation and other efforts to mitigate the effects of the pandemic.76

Despite these concerns, the understandable desire to focus on priority issues and to conserve strained legislative capacity during emergencies has led several states to pass rules or laws that give their legislative leadership more power to control the agenda. For example, Colorado’s emergency law creates an Executive Committee that has the power to determine what legislation is mission-critical and to cut off legislators from calling up for consideration more than a particular number of bills. In California, the head of the Senate is allowed to summarily remove or replace members of any standing committee.77

No matter how well-intentioned, these expanded powers are ripe for abuse. Leaders who already wield significant power should not have the ability to arbitrarily cut off opposing views. Concentrating more authority in the hands of a small number of members can also exacerbate the risk of corruption.78

The risks associated with granting leaders more power are likely to substantially outweigh the benefits. This is especially true given the substantial power most legislative leaders already enjoy, the potential for virtual meetings and technology to enable something approaching normal order, and the possibility that the Covid-19 pandemic may continue in some form or another for years, as previously noted. Non-emergency business will need to continue even while emergency procedures are in place, and legislative leaders should not be able to stifle democratic debates on those matters.

That being said, there is one circumstance in which legislative leadership should be given additional power in an emergency. In some states, the legislature is constitutionally limited to convening for a set number of days or during a particular date range, and only the governor has the power to call it into emergency session.79 Where feasible, states should vest that power in legislative leaders, as Utah recently did.80

B. Transparency and Openness

Beyond delineating the basic mechanics of meeting and legislating, emergency legislative continuity procedures must preserve transparency and opportunities for public participation in the legislative process—which are often among the first casualties of emergency lawmaking. Many state legislatures have closed their capitol buildings or public galleries.81 Others have adopted virtual session procedures but have made no clear provisions for how the public or press are to have access and provide input.82 In some cases, states have suspended their open government laws, though it appears in most cases that these moves are bluntly crafted efforts to facilitate virtual meetings more than they are motivated by a desire to act in secrecy.83

Given the available technological capabilities, the public has every right to expect that the legislators will continue to operate with roughly the same degree of transparency and openness that would exist in ordinary circumstances. Several organizations have put forward thoughtful suggestions for how they can do so, with which we largely concur.84 In our view, the most important guidelines are the following:

- Provide ample public notice for all proceedings. There should be widespread public notice of scheduled proceedings, including committee hearings.

- Preserve real-time public access. The public should have the ability to easily observe meetings live and be given opportunities to participate equivalent to doing so in person—ideally via video conference but in the very least by telephone and through written testimony. If audio or video coverage of a meeting or proceeding is interrupted, the meeting should be suspended absent clear extenuating circumstances.

- Clearly identify all participating legislators. Legislatures should ensure that members of any public body are clearly identified and audible, and that the chair of the proceeding clearly states which members are participating remotely, both at the beginning of and throughout the meeting.

- Make recordings and other documents publicly available. All open sessions or meetings should be recorded. The recordings should promptly be made available to the public via a government website. Public documents used during proceedings, including testimony or legislative language, should also be made available, as they would under normal circumstances.

Implementing these recommendations will give the public the ability to continue participating in legislative proceedings and holding their elected representatives accountable during a critical time.

Conclusion

The United States cannot effectively confront emergencies without its legislatures. In 1861, after confederate forces started the Civil War by firing on Fort Sumter, President Lincoln took two actions simultaneously. One was to muster the state militias. The second was to call Congress into emergency session “to consider, and determine, such measures as, in their wisdom, the public safety, and interest, may seem to demand.”85 When the nation confronted its greatest crisis more than 150 year ago, Congress was indispensable to preserving the Union.

Today, amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, Congress and state legislatures must similarly remain fully engaged in the business of governing, and take the steps necessary to fulfill their constitutional roles.

The authors thank Brennan Center Research and Program Associate Gareth Fowler for outstanding research and technical assistance, and Brennan Center Staff Writer Timothy Lau, Web Producer Justin Charles, and the rest of the Center’s Communications team for their help in editing this paper and readying it for publication. Brennan Center Vice President for Democracy Wendy Weiser helped develop the original idea for this paper and contributed important insights. Brennan Center President Michael Waldman also provided valuable feedback and ideas, as did Policy Counsel Maya Efrati. All errors are the responsibility of the authors.

Endnotes

-

1

As of May 13, 2020. National Conference of State Legislatures, “2020 State Legislative Session Calendar,” accessed May 13, 2020, https://www.ncsl.org/research/about-state-legislatures/2020-state-legislative-session-calendar.aspx. -

2

Mike DeBonis and Paul Kane, “Senate to Return to Washington as Congress Struggles to Reconcile Constitutional Duties with Risk of Pandemic,” Washington Post, May 2, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/senate-to-return-to-washington-with-congress-struggling-to-reconcile-constitutional-duties-with-risk-of-pandemic/2020/05/02/fba5a35c-8bd7–11ea-ac8a-fe9b8088e101_story.html. -

3

Andrew DeMillo, “Arkansas Lawmakers Meet at Arena over Coronavirus Concerns,” AP, Mar. 26, 2020, https://apnews.com/a8f4d3abe4f9769eca1f7c578da80b45. -

4

Paul Egan and Kathleen Gray, “Michigan Legislature Extends Emergency Declaration Through April 30,” Detroit Free Press, Apr. 7, 2020, https://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/2020/04/07/watch-live-michigan-house-senate-reconvene/2960049001/. -

5

Jacob Pramuk, “House Set to Pass $484 Billion Coronavirus Bill to Boost Small Business, Hospitals and Testing,” CNBC, Apr. 23, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/23/coronavirus-updates-house-to-pass-small-business-relief-bill.html. -

6

Ben Winslow, “The Utah State Legislature’s Virtual Special Session Dealing with COVID-19 is Under Way,” FOX 13, Apr. 17, 2020, https://www.fox13now.com/news/coronavirus/local-coronavirus-news/the-utah-state-legislatures-virtual-special-session-dealing-with-covid-19-is-under-way. -

7

William Booth, “U.K.’s Zoom Parliament Launches with a Few Glitches but Shows That Virtual Democracy May Work for a While,” Washington Post, Apr. 22, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/uk-zoom-parliament/2020/04/22/d3a38682–8496–11ea-81a3–9690c9881111_story.html; Ryan Tumilty, “COVID-19 Canada: First ‘Virtual Parliament’ Brings Accountability with a Few Technical Glitches,” National Post, Apr. 29, 2020, https://nationalpost.com/news/politics/covid-19-canadian-politics-first-virtual-parliament-brings-accountability-with-a-few-technical-headaches. -

8

Authorizing Remote Voting by Proxy in the House of Representatives and Providing for Official Remote Committee Proceedings During a Public Health Emergency Due to a Novel Coronavirus, and for Other Purposes., H.Res.965, 116th Cong. (2020), available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-resolution/965. -

9

Katelyn Burns, “Pressure is Growing to Allow Members of Congress to Vote Remotely Amid Coronavirus Concerns,” Vox, Mar. 18, 2020, https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2020/3/18/21185412/congress-vote-remotely-coronavirus-katie-porter; Scott R. Anderson and Margaret Taylor, “Congress Dawdles on Remote Voting,” Lawfare, May 6, 2020, https://www.lawfareblog.com/congress-dawdles-remote-voting. -

10

National Conference of State Legislatures, “COVID-19: State Actions Related to Legislative Operations,” accessed May 13, 2020, https://www.ncsl.org/research/about-state-legislatures/covid-19-state-actions-related-to-legislative-operations.aspx. -

11

Juliegrace Brufke, “Coronavirus in Congress: Lawmakers who Have Tested Positive,” The Hill, last updated Apr. 9, 2020, https://thehill.com/homenews/news/489911-coronavirus-in-congress-lawmakers-who-have-tested-positive. -

12

Ballotpedia, “Government Official, Politician, and Candidate Deaths, Diagnoses, and Quarantine Due to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic, 2020,” accessed May 13, 2020, https://ballotpedia.org/Government_official,_politician,_and_candidate_deaths,_diagnoses,_and_quarantines_due_to_the_coronavirus_(COVID-19)_pandemic,_2020. -

13

James Madison, “Federalist #44,” retrieved from Congress,gov, “The Federalist Papers,” https://www.congress.gov/resources/display/content/The+Federalist+Papers#TheFederalistPapers-44. -

14

U.S. Const. art. I, §§ 7–9. -

15

Benjamin Ginsberg and Kathryn Wagner Hill, Congress: The First Branch (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 13–14, 43–45. See also Josh Chafetz, Congress’s Constitution: Legislative Authority and the Separation of Powers (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017). -

16

All 50 states have a government structure that mimics to some degree the three branches of the federal government; some have suggested that the federal Constitution may require this model for the states. However, there is a great deal of variation across the states in terms of the balance of power between the different branches. See Michael C. Dorf, “The Relevance of Federal Norms for State Separation of Powers,” Roger Williams University Law Review 4 (1998): 52. See National Conference of State Legislatures, State Legislative Policymaking in an Age of Political Polarization, Center for Legislative Strengthening, 2018, https://www.ncsl.org/Portals/1/Documents/About_State_Legislatures/Partisanship_030818.pdf; National Conference of State Legislatures and National Legislative Program Evaluation Society, Ensuring the Public Trust 2015: Program Policy Evaluation’s Role in Serving State Legislatures, 2015, https://www.ncsl.org/Portals/1/Documents/nlpes/NLPESEnsuringThePublicTrust2015_3.pdf. -

17

Our colleague Elizabeth Goitein has explored the threat that unfettered executive authority can pose to liberal democratic values in the context of the president’s emergency powers. See Elizabeth Goitein, “The Alarming Scope of the President’s Emergency Powers,” The Atlantic, Jan./Feb. 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/01/presidential-emergency-powers/576418/. While a genuine crisis often does require executive officials to exercise increased authority, their power must still be cabined and appropriately checked. See Elizabeth Goitein, “The Coronavirus is a Real Crisis. The Border Wall Obviously Wasn’t,” Washington Post, Mar. 18, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/03/18/coronavirus-is-real-crisis-border-fence-obviously-wasnt/. This is a concern at the state level as well. According to an analysis prepared by CDC experts during a declared emergency “35 states … explicitly permit governors to suspend or amend both statutes and regulations.” Gregory Sunshine et al., “An Assessment of State Laws Providing Gubernatorial Authority to Remove Legal Barriers to Emergency Response,” Health Security 17 (2019): 156, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30942620. -

18

The recent controversy over Wisconsin’s April 7 election is a case in point. After the legislature refused to act, the state’s governor issued an executive order postponing in-person voting, an action that was overturned by the state’s supreme court. Natasha Korecki and Zach Montellaro, “Wisconsin Supreme Court Overturns Governor, Orders Tuesday Elections to Proceed,” Politico, Apr. 6, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/2020/04/06/wisconsin-governor-orders-stop-to-in-person-voting-on-eve-of-election-168527. -

19

See Amy Gutmann and Dennis Thompson, Why Deliberative Democracy? (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 20; Jeremy Waldon, “Principles of Legislation,” in The Least Examined Branch: The Role of Legislatures in the Constitutional State, ed. Richard W. Bauman and Tsvi Kahana (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 22– 23. This is not to discount the significance of extreme gerrymandering and other problems that undermine the representative character of particular legislative bodies. See Michael Li and Annie Lo, “What Is Extreme Gerrymandering?,” Brennan Center for Justice, Mar. 22, 2019, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/what-extreme-gerrymandering. -

20

Carl Hulse and Nicholas Fandos, “As Lawmakers Report Exposure, Congress Grapples with Virus Response,” New York Times, Mar, 12, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/09/us/congress-coronavirus.html; Adam Beam, “California Legislature Suspends until April 13 Amid Outbreak,” AP, Mar. 17, 2020, https://apnews.com/5e7be7d1b9c8bc3d44817001e04de05f; and Meghan Lopez, “Colorado Lawmakers Considering Possibility of Suspending Legislative Session,” Denver Channel, Mar. 13, 2020, https://www.thedenverchannel.com/news/national/coronavirus/colorado-lawmakers-considering-possibility-of-suspending-legislative-session. In response to the Spanish influenza pandemic, the House of Representatives agreed to an extended series of recesses interspersed with brief pro forma sessions where it often lacked the members necessary to form a quorum. In one such session, with fewer than 50 members present, congressional leaders from both parties agreed to consider a bill to recruit more doctors to the Public Health Service under a unanimous consent agreement where all members agreed not to ask for a quorum call. The rule was adopted 29–19, and the bill passed without objection. See United States House of Representatives, “Sick Days,” Dec. 17, 2018, https://history.house.gov/Blog/2018/December/12–14-Flu/. While such rule changes may have been necessary for the House to continue functioning in 1918, modern communications technologies should allow Congress to respond to the present crisis without extreme alterations of quorum practices. -

21

For example, Congress stayed in session and passed laws through early July of 1864, even as Confederate troops in the Shenandoah Valley prepared to launch an attack on Washington, DC. Confederate and Union forces fought the Battle of Fort Stevens, within the District of Columbia, on July 11–12. See “Statutes at Large: 38th Congress,” Library of Congress, accessed May 7, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/38th-congress.php; Leah Binkovitz, “The Battle in Our Backyard: Remembering Fort Stevens,” Smithsonian Magazine, July 11, 2012, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/the-battle-in-our-backyard-remembering-fort-stevens-1693525/. -

22

National Conference of State Legislatures, “Continuity of Legislature During Emergency,” accessed May 7, 2020, https://www.ncsl.org/research/about-state-legislatures/continuity-of-legislature-during-emergency.aspx. -

23

Paul Kane, “Congress in Grip of Confusion, Fear over Coronavirus Unsure Whether to Stay or Go,” Washington Post, Mar. 10, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/powerpost/congress-in-grip-of-confusion-fear-over-coronavirus-unsure-whether-to-stay-or-go/2020/03/09/2528a34c-6233–11ea-845d-e35b0234b136_story.html. -

24

The California state legislature stayed in session through the summer of 2018 as multiple wildfires ravaged parts of the state, blowing smoke into the state capital of Sacramento. The legislature ultimately passed a major wildfire prevention bill in August. Jordan Cutler-Tietjen, “Here’s the Air Quality Outlook for July 4 and Beyond, Amid Northern California Wildfires,” Sacramento Bee, July 3, 2018, https://www.sacbee.com/news/california/fires/article214265469.html; Katy Murphy, “California Wildfire Legislation Includes PG&E ‘Bailout,’” Mercury News, Aug. 31, 2018, https://www.mercurynews.com/2018/08/31/california-passes-net-neutrality-bill-on-final-day-of-legislative-session/. Following Hurricane Katrina, the Louisiana state legislature was in joint session in Baton Rouge a few weeks after the hurricane hit New Orleans. Louisiana State Senate, “LA Senate & House to Hold Special Meeting to Receive an Update on Hurricane Katrina Recovery from Governor Blanco,” Sept. 13, 2005, http://senate.legis.state.la.us/CommunicationOffice/NewsReleases/2005/09–13–2005.htm; “Louisiana’s Blanco Vows to Rebuild,” CNN, Sept. 15, 2005, http://edition.cnn.com/2005/POLITICS/09/14/katrina.gov.blanco/. The state legislature then met again in October, after Hurricane Rita hit Baton Rouge, and was called into an extraordinary legislative session in November of that year to mass major relief legislation. Louisiana State Senate, “Joint Budget Committee Takes On Key Role In Approval of Appropriations of Federal Disaster Aid to State Agencies & Local Governments,” Oct. 4, 2005, http://senate.legis.state.la.us/CommunicationOffice/NewsReleases/2005/10–04–2005.htm; Louisiana House Legislative Services, Highlights of the 2005 First Extraordinary Session and the 2006 First Extraordinary Session of the Louisiana Legislature, 2006, https://house.louisiana.gov/H_Highlights/Highlights_051ES_061ES.pdf; and Louisiana State Legislature, “Session Information for the 2005 First Extraordinary Session,” accessed May 7, 2020, https://www.legis.la.gov/Legis/SessionInfo/SessionInfo_051ES.aspx. -

25

See, e.g. U.S. Const. art. I, § 8. Both federal and state laws do sometimes allow executive officers to redirect appropriated funds, but as noted there are compelling reasons to limit such circumstances. See note 17. -

26

“Coronavirus: Congress Passes $484bn Economic Relief Bill,” BBC, Apr. 24, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52398980. -

27

National Conference of State Legislatures, “State Action on Coronavirus (COVID-19),” accessed May 7, 2020, https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-action-on-coronavirus-covid-19.aspx. -

28

Jesse Pound, “State and Local Governments Face Budget Crunch, Hurting Hopes for a Quick Economic Recovery,” CNBC, Apr. 12, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/12/state-and-local-governments-face-budget-crunch-hurting-hopes-for-a-quick-economic-recovery.html; Allan Smith, “Financial Doomsday: State, Local Governments Face Layoffs, Service Cuts, Projects Derailed,” NBC, Apr. 22, 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/financial-doomsday-state-local-governments-face-layoffs-service-cuts-projects-n1188246; and Tony Room, “Cities and States Brace for Economic ‘Reckoning,’ Eyeing Major Cuts and Fearing Federal Coronavirus Aid Isn’t Enough,” Washington Post, Apr. 10, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/10/cities-states-coronavirus-budgets/. -

29

Dr. Anthony Fauci, interview by Jake Tapper, State of the Union, CNN, Apr. 12, 2020, available at http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/2004/12/sotu.01.html; Hites Ahir, Nicholas Bloom, and David Furceri, “Global Uncertainty Related to Coronavirus at Record High,” IMFBlog, Apr. 4, 2020, https://blogs.imf.org/2020/04/04/global-uncertainty-related-to-coronavirus-at-record-high/. -

30

Claudia Grisales, “Trump To Sign $8 Billion Coronavirus Response Package Friday,” NPR, Mar. 4, 2020 https://www.npr.org/2020/03/04/812109864/bipartisan-negotiators-reach-deal-for-roughly-8-billion-for-coronavirus-response; Claudia Grisales, Susan Davis, and Kelsey Snell, “President Trump Signs Coronavirus Emergency Aid Package,” NPR, Mar. 18, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/03/18/817737690/senate-passes-coronavirus-emergency-aid-sending-plan-to-president; and “What’s in the $2 Trillion Coronavirus Stimulus Bill,” CNN, Mar. 26, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/25/politics/stimulus-package-details-coronavirus/index.html. -

31

E.g. Lewis Kamb, “Inslee Suspends Some Parts of Open-Government Laws Amid Coronavirus Crisis,” Seattle Times, Mar. 25, 2020, https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/inslee-suspends-some-parts-of-open-government-laws-amid-coronavirus-crisis/; Laura Bednar, “Independence Shifts to Online Platform for Public Meetings Due to Coronavirus Crisis,” Cleveland.com, Apr. 18, 2020, https://www.cleveland.com/community/2020/04/independence-shifts-to-online-platform-for-public-meetings.html; Scott Logan, “Idaho Lawmakers OK $1.3 Million to Ensure Government Services in Coronavirus Crisis,” IdahoNews, Mar. 16, 2020, https://idahonews.com/news/coronavirus/jfac-oks-13-million-to-ensure-essential-government-services-in-crisis; and “Kentucky Lawmakers Pass COVID-19 Relief for Schools,” WKYT, Mar. 19, 2020, https://www.wkyt.com/content/news/Kentucky-lawmakers-pass-COVID-19-relief-for-schools-568951711.html. -

32

Cole Lauterbach, “Ducey Signs Bill Expanding Access to Unemployment Due to COVID-19,” The Center Square, Mar. 27, 2020, https://www.thecentersquare.com/arizona/ducey-signs-bill-expanding-access-to-unemployment-due-to-covid-19/article_815afd9c-7073–11ea-b3d2–433d99119219.html; Christopher Gavin, “An Eviction and Foreclosure Moratorium is Now in Effect in Mass. During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Here’s What to Know,” Boston.com, Apr. 21, 2020, https://www.boston.com/news/coronavirus/2020/04/21/massachusetts-eviction-foreclosure-moratorium-coronavirus. -

33

Wendy R. Weiser and Max Feldman, “How to Protect the 2020 Vote from the Coronavirus,” Brennan Center for Justice, Mar. 16, 2020, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/policy-solutions/how-protect-2020-vote-coronavirus. -

34

E.g. Audrey Hackett, “Ohio Moves to Mail-In Voting,” Yellow Springs News, Apr. 6, 2020, https://ysnews.com/news/2020/04/ohio-moves-to-mail-in-voting; Lindsay Whitehurst, “Utah OKs Holding Primary Entirely by Mail Amid Coronavirus,” AP, Apr. 16, 2020, https://apnews.com/26002ad8b3a1eef41deef71e00c69ae7; and Fritz Esker, “La. Legislature Approves Emergency Election Plan,” Louisiana Weekly, May 4, 2020, http://www.louisianaweekly.com/la-legislature-approves-emergency-election-plan/. -

35

Brennan Center for Justice, “Preparing Your State for an Election Under Pandemic Conditions,” last updated Apr. 27, 2020, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/preparing-your-state-election-under-pandemic-conditions. -

36

Lawrence Norden et al., “Estimated Costs of Covid-19 Election Resiliency Measures,” Brennan Center for Justice, last updated Apr. 18, 2020, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/estimated-costs-covid-19-election-resiliency-measures. -

37

L. Elaine Halchin and Frederick M. Kaiser, Congressional Oversight, Congressional Research Service, 2012, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/97–936.pdf. -

38

Telford Taylor, Grand Inquest: The Story of Congressional Investigations (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1955); “Truman Committee Exposes Housing Mess,” Life, Nov. 30, 1942, available at https://books.google.com/books?id=RkEEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA45#v=onepage&q&f=false; and U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Subcommittee on Management, Integration, and Oversight of the Committee on Homeland Security, An Examination of Federal 9/11 Assistance to New York: Lessons Learned in Preventing Waste, Fraud, Abuse, and Lax Management, 109th Cong., 2006, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CPRT-109HPRT20452/html/CPRT-109HPRT20452.htm. -

39

Neil M. Barofsky, “Why We Desperately Need Oversight of the Coronavirus Stimulus Spending,” New York Times, Apr. 13, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/13/opinion/coronavirus-stimulus-oversight.html. -

40

Bharat Ramamurti, “I’m Overseeing the Coronavirus Relief Bill. The Strings Aren’t Attached.,” Washington Post, Apr. 16, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/16/opinion/coronavirus-oversight-congress-trillions.html; Zachary Cohen et al., “Amid Coronavirus, Trump Seizes Chance to Carry out a Long-Desired Purge of Government Watchdogs,” CNN, Apr. 8, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/08/politics/trump-attacks-watchdog-inspectors-general-government-oversight/index.html; and Mike DeBonis and John Hudson, “Fired Inspector General Was Examining Whether Pompeo Had a Staffer Walk His Dog, Handle Dry Cleaning, Officials Say,” Washington Post, May 17, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/state-department-inspector-general-steve-linick-mike-pompeo/2020/05/17/daf5170a-98a7–11ea-b60c-3be060a4f8e1_story.html. -

41

Adam Beam, “California Legislature OKs $1 Billion for Coronavirus,” KPBS, Mar. 16, 2020, https://www.kpbs.org/news/2020/mar/16/california-legislature-oks-1-billion-coronavirus/; Jim Brennan, “State Budget Includes Extensive Cutbacks but We Don’t Know What They Are Yet,” Gotham Gazette, Apr. 16, 2020, https://www.gothamgazette.com/opinion/9309-new-york-state-budget-extensive-cutbacks-mystery-transparency; and Craig Mauger, “Whitmer Signs Emergency COVID-19 Response Bills, Vetoes Nearly $80M in Other Spending,” Detroit News, Mar. 30, 2020, https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/michigan/2020/03/30/whitmer-signs-emergency-covid-19-response-bills-limits-other-spending/5085760002/. -

42

E.g., Or. Const. art. X-A, § 2. -

43

Robert Kuznia, “The Timetable for a Coronavirus Vaccine is 18 Months. Experts Say That’s Risky,” CNN, Apr. 1, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/31/us/coronavirus-vaccine-timetable-concerns-experts-invs/index.html. -

44

Rosie Perper, “A Federal Plan to Tackle the Coronavirus Pandemic Warns It 'Will Last 18 Months or Longer’ and Could Include ‘Multiple Waves’,” Business Insider, Mar. 17, 2020, https://www.businessinsider.com/us-coronavirus-warning-pandemic-will-last-18-months-multiple-waves-2020–3. -

45

At least 13 states had some emergency rule changes pre-positioned long before the current public health crisis. But many of the states that had the foresight to deal with potential emergencies limited their laws’ applicability to “enemy attacks.” See National Conference of State Legislatures, More Resources for NCSL’s Website on Continuity of the Legislature During an Emergency, 2020, 8–12, https://www.ncsl.org/Documents/About_State_Legislatures/more_resources_COG_Legislatures.pdfhttps://www.ncsl.org/Documents/About_State_Legislatures/more_resources_COG_Legislatures.pdf. States that do not have established emergency procedures should consider creating them now, and the states that already do should review them to make sure that they cover a broad range of events, including pandemics. Both Washington and Oregon have recently done so and may provide useful models. Washington state amended its constitution in 2019 to add “catastrophic incidents” to provisions regarding legislative powers in an emergency. Joseph O’Sullivan, “Washington Voters Saying Yes to Constitutional Amendment for Stronger State Disaster-Planning,” Seattle Times, Nov. 6, 2019, https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/politics/election-results-2019-senate-joint-resolution-8200-constitutional-amendment-disaster-earthquake-planning-washington-state/. In Oregon, “catastrophic disaster” legislative procedures include “natural or human-caused event[s] that: (a) Results in extraordinary levels of death, injury, property damage or disruption of daily life in this state; and (b) Severely affects the population, infrastructure, environment, economy or government functioning of this state.” Or. Const. art. X-A, § 4. Likewise, in Wisconsin, disaster “means a severe or prolonged, natural or human-caused, occurrence that threatens or negatively impacts life, health, property, infrastructure, the environment, the security of this state or a portion of this state, or critical systems, including computer, telecommunications, or agricultural systems.” Wis. Stat. § 13.42 (2009); see also Continuity of Government Commission, Preserving Our Institutions: The Continuity of Congress, 2003,https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/continuityofgovernment.pdf (focusing on mass casualty events in the wake of a terrorism attack and the need to rapidly reconstitute Congress). -

46

Walter J. Oleszek et al., Congressional Procedures and the Policy Process, 11th ed. (Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2019), 8; see also Robert C. Byrd, The Senate, 1789–1989: Addresses on the History of the United States Senate (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1989). -

47

Oleszek et al., Congressional Procedures, 8. -

48

Thomas Jefferson, Manual of Parliamentary Practice (Carlisle, MA: Applewood Books, 1993), 2–3. -

49

Waldron, “Principles of Legislation,” 22–23; Jane Schacter, “Political Accountability, Proxy Accountability and the Democratic Legitimacy of Legislatures,” in The Least Examined Branch: The Role of Legislatures in the Constitutional State, ed. Richard W. Bauman and Tsvi Kahana (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 45–50 (elaborating on the accountability axiom and questioning its practical implementation). -

50

See Kenneth A. Shepsle and Barry R. Weingast, “Positive Theories of Congressional Institutions,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 19(2) (1994): 149–153. -

51

Gary W. Cox, “On the Effects of Legislative Rules,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 25 (2000): 187; Oleszek et al., Congressional Procedures, 416–417. -

52

At least one legislator called for legislative leadership to act creatively to avoid an in-person meeting. Mallory McMorrow, “State Senator: Legislature’s In-Person Meeting Puts Michigan at Risk,” Detroit Free Press, Apr. 3, 2020, https://www.freep.com/story/opinion/contributors/2020/04/03/coronavirus-michigan-legislature-social-distancing/2940162001/. The decision whether and how to convene devolved into partisan bickering. Abigail Censky, “Lawmakers Defy Warnings, Continue to Meet In Capitols Across the Country,” NPR, Apr. 8, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/04/08/828952509/lawmakers-defy-warnings-continue-to-meet-in-capitals-across-the-country. -

53

See National Conference of State Legislatures, “Continuity of Government in Constitutions,” accessed May 7, 2020, https://www.ncsl.org/research/about-state-legislatures/examples-of-constitutional-provisions-relating-to-continuity-of-government.aspx. Some have suggested that the U.S. Constitution may require in-person meetings, but as one scholar has noted, the Constitution gives each house of Congress broad discretion to “determine the Rules of its Proceedings,” which are generally unreviewable in court. While the framers could not have anticipated virtual attendance by members, the same is true for many other procedures used by Congress today whose constitutionality has never been questioned. See Deborah Pearlstein, “Zoom Congress Is Perfectly Constitutional,” The Atlantic, Apr. 16, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/zoom-congress-perfectly-constitutional/610057/ (quoting U.S. Const. art. I, § 5). See also Daniel Hemel, “Congress Can’t Meet Remotely. The Coronavirus Might Mean It Has To.,” Washington Post, Mar. 10, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/03/10/coronavirus-congress-quorum/; United States v. Ballin, 144 U.S. 1 (1892) (holding that the U.S. Constitution gives the Speaker of the House broad leeway in how she recognizes attendance for purposes of assessing a quorum). -

54

U.S. Const. art. I, § 5. -

55

Many have suggested that the pandemic could lead to broader acceptance of remote work under normal circumstances, but it is not clear to us that this logic should extend to Congress or state legislatures. This issue may merit further study, but we do not believe the pandemic should be a catalyst for any permanent changes to regular legislative operations. -

56

At least one Senate committee recently was forced to rapidly alter its traditional in-person hearing practice when multiple attendees—senators and witnesses—were forced to self-quarantine after exposure to the coronavirus. See David Lim, “Alexander to Remotely Chair Coronavirus Hearing after Staffer Tests Positive for Virus,” Politico, May 10, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/2020/05/10/alexander-coronavirus-hearing-staffer-positive-248512. In addition, several states have begun efforts to operate remotely. See, e.g. Lee Davidson, “Amid Coronavirus Threat, Utah Legislature Moves to Allow Remote Meetings,” Salt Lake Tribune, Mar. 11, 2020, https://www.sltrib.com/news/politics/2020/03/11/amid-coronavirus-threat/; Jonathan Mohr, “Remote Rules Meeting a Likely Preview for Things to Come,” Minnesota House of Representatives, Apr. 1, 2020, https://www.house.leg.state.mn.us/SessionDaily/Story/15213; and Jon Evans, “General Assembly to Begin Video Streaming of NC House Remote Committee Meetings,” WECT, Apr. 9, 2020, https://www.wect.com/2020/04/09/general-assembly-begin-video-streaming-nc-house-remote-committee-meetings/. -

57

Not only have other national legislatures moved to virtual meetings in response to the pandemic, but the House itself already uses technology for certain critical functions, like tabulating votes. See Frederick Hill, “If Parliament Can Vote Remotely, Congress Can Too,” Washington Post, Apr. 23, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/04/23/congress-remote-proxy-voting-coronavirus/. -

58

Timothy LaPira and James Wallner, “In Congress, Assembled: A Virtual Congress Creates More Problems Than It Solves,” LegBranch, Mar. 26, 2020, https://www.legbranch.org/in-congress-assembled-a-virtual-congress-creates-more-problems-than-it-solves/; see also Joshua Huder, “Remote Voting by Congress? Not So Fast,” LegBranch, Mar. 16, 2020, https://www.legbranch.org/remote-voting-by-congress-not-so-fast/. -

59

Several members of Congress have engaged in mock virtual hearings in recent weeks in order to demonstrate their feasibility. Margaret Taylor, “Former Congressman Brian Baird and Daniel Schuman on How Congress Can Continue to Function Remotely,” The Lawfare Podcast, Podcast audio, Apr. 20, 2020, https://www.lawfareblog.com/lawfare-podcast-former-congressman-brian-baird-and-daniel-schuman-how-congress-can-continue-function. See also Rachel Orey and Michael Thorning, “Five New Recommendations for Virtual Congressional Hearings,” LegBranch, May 11, 2020, https://www.legbranch.org/five-new-recommendations-for-virtual-congressional-hearings/. -

60

A proposal in Louisiana does exactly that. H.R. 18, 2020 Leg., 2020 Reg. Sess. (La. 2020), available at https://www.legis.la.gov/legis/ViewDocument.aspx?d=1167905. New York’s Assembly passed a provision restricting members to only one opportunity to speak and only for 15 minutes. Assemb. E00854, 203rd Leg., 2020 Legis. Sess. (N.Y. 2020), available at https://nyassembly.gov/leg/?default_fld=&leg_video=&bn=E00854&term=2019&Summary=Y&Actions=Y&Text=Y. Colorado’s law limits the number of bills that its members may introduce during the emergency. Colo. General Assemb. J. Rule 44(c)(2), available at https://www.leg.state.co.us/CLICS/cslFrontPages.nsf/FileAttachVw/2019Rules/$File/2019CombinedLegislativeRules.pdf. -

61

If there is one lesson to take away from the crisis, it is the importance of planning ahead both logistically and procedurally. In 2009, the Wisconsin state legislature passed a law setting up a system for virtual legislature and committee meetings. S.B. 227, 99th Leg., Reg. Sess. (Wis. 2010), available at https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2009/related/acts/363. The law established a clear system for conducting virtual meetings and made only light changes to procedures, for example requiring that each senator’s identity be verified, that all participating members be able to simultaneously hear or read proceedings, and that all documents be available to the lawmakers. As a result of the longstanding law, when the scope of the coronavirus crisis became clear more than a decade later, a political settlement between the parties on how to proceed was already in place. In late March, the state’s House majority leader and Senate president held several dress rehearsals for a virtual legislative meeting. Rather than disputing procedure, only thing Wisconsin had to deal with during the dress rehearsal was technical difficulties. Riley Verrerkind, “State Senate Holds Dress Rehearsal in Anticipation of Wisconsin’s First-Ever Virtual Session,” Wisconsin State Journal, Mar. 26, 2020, https://madison.com/wsj/news/local/govt-and-politics/state-senate-holds-dress-rehearsal-in-anticipation-of-wisconsin-s/article_dd3e87c6–14f4–5b04–9ce1–146e29621f5f.html. Of course, such planning does not necessarily result in wise decision-making overall. Notwithstanding the foresight of Wisconsin’s past legislative leaders in planning for emergencies, the current legislature’s actual conduct with respect to various aspects of the Covid-19 crisis has been widely criticized. See Felicia Sonmez, “Wisconsin Legislature Comes under Fire for ‘Unconscionable’ Decision to Hold Primary Amid Coronavirus Pandemic,” Washington Post, Apr. 5, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/wisconsin-legislature-comes-under-fire-for-unconscionable-decision-to-hold-primary-amid-coronavirus-pandemic/2020/04/05/06016460–7780–11ea-9bee-c5bf9d2e3288_story.html. But the ability to convene and conduct business is a necessary predicate to any action, good or bad. -

62

For instance, while we sympathize with a New York Assembly provision providing that “no technical failure on the part of an individual member or a group of members that breaks their remote connection to the proceedings shall invalidate any action taken by a majority of the Assembly,” it probably goes too far in excusing problems that undermine the integrity of proceedings. Assemb. E00854, 203rd Leg., 2020 Legis. Sess. (N.Y. 2020). -

63

There is debate over what proportion of a representative assembly should be required as a quorum. During the constitutional convention, George Mason and Maryland’s John Mercer debated different proportions. Mercer worried that a high proportion would hobble the ability of the legislature to act since it would “put it in the power of a few by seceding at a critical moment.” George Mason argued the reverse, concerned that a lower quorum requirement would “allow a small number of members of the two houses to make laws.” The debate continues to this day. See Mike Dorf, “Super-majority Quorum Requirements,” Dorf on Law, Feb. 21, 2011, http://www.dorfonlaw.org/2011/02/super-majority-quorum-requirements.html. However, the consensus proportion is one half. See John Bryan Williams, “How to Survive a Terrorist Attack: The Constitution’s Majority Quorum Requirement and the Continuity of Congress,” William & Mary Law Review 48 (2006): 1025, 1033, https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol48/iss3/5. We express no opinion on this other than to remark that current rules, whatever they may be, should hold presumptive sway. We also note that in some bodies in which members are divided into parties, specific quorum rules also serve to prevent single-party action, by explicitly requiring that a proportion of the membership be present and that at least one of them be a member of the minority party. See, e.g. the rules of the Senate Judiciary Committee, which requires that two members of the minority party be present for transacting business. United States S. Comm. on the Judiciary Rule III(1), available at https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/about/rules. This is not the time to substantively alter such critical rules. -

64

U.S. Const. art. I, § 5. -

65

Karl Kurtz, “Legislative Walkouts are Nothing New,” The Thicket at State Legislatures, Feb. 18, 2011, https://ncsl.typepad.com/the_thicket/2011/02/legislative-walkouts-are-nothing-new.html. (Noting that in Indiana, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, and Vermont, two-thirds of the members make up a quorum, and in Wisconsin, three-fifths of the members are required to act on budget and tax bills). -

66

For example, Georgia’s emergency or disaster procedure law allows for its General Assembly to “suspend the operation of any and all constitutional rules governing the procedure of both the House of Representatives and the Senate as it deems necessary during the period of emergency or disaster.” Ga. Code Ann. § 38–3–53; see also Continuity of Government Commission, Preserving Our Institutions. -

67

Or. Const. art. X-A, § 4. This year, after the coronavirus outbreak, Oregon’s legislature considered a proposal to drop its quorum requirement but rejected it. S.J.Res. 201, 2020 Legis. Assemb., 2020 Sess. (Or. 2020), available at https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2020R1/Measures/Overview/SJR201. -

68

For instance, the U.S. Constitution gives the Speaker of the House broad leeway in how she recognizes attendance for purposes of assessing a quorum. Ballin, 144 U.S. 1; Pearlstein, “Zoom Congress.” -

69

In Massachusetts, for example, Republican and Democratic legislators held extended negotiations over the state legislature’s proposed virtual voting and debate procedures. An early version of the rule changes would have limited legislators’ opportunities to engage in debate and created other procedural barriers to full participation. Ultimately, the Democratic majority agreed to a series of changes that satisfied the Republican caucus. See State House News Service, “Lawmakers Set Rules for Debate, Voting in Remote Sessions Amid Coronavirus Pandemic,” Boston Herald, May 5, 2020, https://www.bostonherald.com/2020/05/05/lawmakers-set-rules-for-debate-voting-in-remote-sessions-amid-coronavirus-pandemic/. -

70

See, e.g., Assemb. E00854, 203rd Leg., 2020 Legis. Sess. (N.Y. 2020) (deeming all legislators to have voted in the affirmative unless they specifically enter a negative vote). In Missouri, the legislature contemplated grouped votes in lieu of roll-call votes. Kaitlyn Schallhorn, “Lawmakers Returning to Capitol: What to Know about Procedural Changes,” Missouri Times, Apr. 6, 2020, https://themissouritimes.com/lawmakers-returning-to-capitol-what-to-know-about-procedural-changes/. -

71

The Brennan Center has criticized unrestricted proxy voting in New York legislative committees for promoting absenteeism and lack of accountability. See Jeremy M. Creelan and Laura M. Moulton, “The New York State Legislative Process: An Evaluation and Blueprint for Reform,” Brennan Center for Justice, July 21, 2004, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/new-york-state-legislative-process-evaluation-and-blueprint-reform. -

72

See, e.g., Congressional Research Service, Proxy Voting and Polling in Senate Committee, 2015, 4–5, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RS/RS22952. -

73

H.R. 1001, 92nd General Assemb., First Extraordinary Sess. (Ark. 2020), available at https://www.arkleg.state.ar.us/Bills/FTPDocument?path=%2FBills%2F2020S1%2FPublic%2FHR1001.pdf; Authorizing Remote Voting by Proxy, H.Res.965. -

74

In Colorado, for example, its emergency law creates an Executive Committee that has the power to determine what legislation is mission-critical and to cut off legislators from calling up for consideration more than a particular number of bills. More Resources for NCSL’s Website, 2–4. In California, the head of the Senate is allowed to summarily remove or replace members of any standing committee. S.R. 86, 2019–2020 S., 2019 –2020 Reg. Sess. (Cal. 2020), available at http://custom.statenet.com/public/resources.cgi?id=ID:bill:CA2019000SR86&ciq=ncsl&client_md=1f47bfb94477c8bec421c383433a31c1&mode=current_text. -

75

See Rick Rojas, “Back in Session, State Legislatures Challenge Governors’ Authority,” New York Times, May 9, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/08/us/coronavirus-state-legislatures.html; Jordain Carney and Maggie Miller, “McConnell under Fire for Burying Election bills in ‘Legislative Graveyard,’” The Hill, July 27, 2019, https://thehill.com/homenews/senate/454967-mcconnell-under-fire-for-burying-election-security-bills-in-legislative-graveyard. -

76

See, e.g., Allan Smith and Julie Tsirkin, “McConnell Taps Brakes on Next Round of Coronavirus Aid as State, Local Governments Plead for Help,” NBC, Apr. 23, 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/congress/mcconnell-taps-breaks-next-round-coronavirus-aid-state-local-governments-n1189541; Sonmez, “Wisconsin Legislature Comes under Fire.” -

77

S.R. 86, 2019–2020 S., 2019 –2020 Reg. Sess. (Cal. 2020). -

78

Corruption among past legislative leaders has been a significant problem, including, for instance, in New York, where legislative leaders already wield more power than those in most other bodies around the country. See Joseph Ax, “Former N.Y. State Legislative Leaders to Face Corruption Trials in November,” Reuters, July 30, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-crime-corruption/former-n-y-state-legislative-leaders-to-face-corruption-trials-in-november-idUSKCN0Q428E20150730. -

79

National Conference of State Legislatures, “Special Sessions,” accessed May 8, 2020, https://www.ncsl.org/research/about-state-legislatures/special-sessions472.aspx. -

80

Dennis Romboy, “2 of 3 Utah Constitutional Amendments Pass,” Deseret News, Nov. 6, 2018, https://www.deseret.com/2018/11/7/20658067/2-of-3-utah-constitutional-amendments-pass. -

81

See, e.g., Tres Savage, “Three Key Questions Hover over the Oklahoma Capitol,” NonDoc, Apr. 27, 2020, https://nondoc.com/2020/04/27/three-key-questions-hover-over-the-oklahoma-capitol/; Ben Winslow, “Economy, Local Health Orders, Re-Opening Utah on Tap for the Legislature’s COVID-19 Special Session,” Fox 13 Salt Lake City, Apr. 15, 2020, https://www.fox13now.com/news/coronavirus/local-coronavirus-news/economy-local-health-orders-re-opening-utah-on-tap-for-the-legislatures-covid-19-special-session; and Jaclyn Driscoll, “Missouri Lawmakers Uncertain When They’ll Return To State Capitol,” KCUR, Mar. 30, 2020, https://www.kcur.org/2020–03–30/missouri-lawmakers-uncertain-when-theyll-return-to-state-capitol. -

82

Annie McDonough, “Will the State Legislature Actually Go Virtual?,” City & State New York, Apr. 5, 2020, https://www.cityandstateny.com/articles/politics/new-york-state/will-state-legislature-actually-go-virtual.html; Briana Bierschbach, “Era of Coronavirus Tests Openness in Minnesota Legislature,” Star Tribune, Mar. 30, 2020, https://www.startribune.com/governing-in-the-era-of-coronavirus-tests-openness/569165092/. -

83

Nick Grube, “Suspension Of Hawaii’s Open Government Laws More Extreme Than Other States,” Honolulu Civil Beat, Mar. 30, 2020, https://www.civilbeat.org/2020/03/suspension-of-hawaiis-open-government-laws-more-extreme-than-other-states/; Massachusetts Municipal Association, “Gov. Signs Order Suspending Parts of Open Meeting Law to Enable Local Decision-Making During COVID-19 Emergency,” accessed May 8, 2020, https://www.mma.org/gov-signs-order-suspending-parts-of-open-meeting-law-to-enable-local-decision-making-during-covid-19-emergency/; and Lewis Kamb, “Inslee Suspends Some Parts of Open-Government Laws Amid Coronavirus Crisis,” Seattle Times, Mar. 25, 2020, https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/inslee-suspends-some-parts-of-open-government-laws-amid-coronavirus-crisis/. -

84

See, e.g., Common Cause, “During COVID-19 State of Emergency, Transparency and Public Access to Government Proceedings Must Be Maintained,” Mar. 18, 2020, https://www.commoncause.org/press-release/during-covid-19-state-of-emergency-transparency-and-public-access-to-government-proceedings-must-be-maintained/; State Innovation Exchange, “Legislating in a Pandemic: Transparent & Remote Governance,” accessed May 8, 2020, https://stateinnovation.org/legislating-in-a-pandemic-transparent-remote-governance/. -

85

“Proclamation Calling Militia and Convening Congress,” Apr. 15, 1861, in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953) IV:332–33, available at https://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln4/1:527.1?rgn=div2;view=fulltext.