A New Vision for Domestic Intelligence

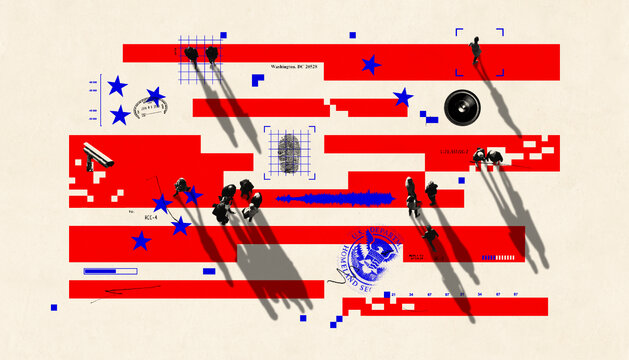

The Department of Homeland Security needs new rules and stronger oversight to better protect civil rights and civil liberties.

Part of

Built from 22 agencies with disparate missions, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) routinely gathers intelligence to guide its strategic and operational activities.1But in the two decades since its inception, scores of incidents have undermined the legitimacy of its intelligence programs.

Congress and the department’s own general counsel and inspector general, among others, have shown that DHS intelligence officers abused their counterterrorism authorities to suppress racial justice protests after the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a police officer.2In support of the Trump administration’s goals to undermine the Black Lives Matter movement and spin an election-season story of anarchy, DHS sent intelligence officers to Portland, Oregon, to surveil protestors, create dossiers on dissidents, and enable U.S. Border Patrol special forces to whisk demonstrators away in unmarked vehicles. DHS’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis (I&A) also surveilled prominent national security journalists and issued intelligence reports on their tweets. This political targeting was enabled by expansive intelligence authorities and a lack of meaningful checks on discretion.

While investigations into the department’s response to the Portland protests provide a rare, detailed look at its operations, the concerns they raise are hardly limited to a single administration. Throughout its history, I&A has generated poorly sourced analysis heavily reliant on social media and on conjecture and caricature to draw sweeping conclusions. Its intelligence products are widely circulated to tens of thousands of police and other government officials nationwide, influencing their threat evaluations and responses to protests and social movements.

Other parts of DHS also raise concerns.3U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has used high-tech surveillance tools to target its critics. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has monitored protestors. These programs, along with those run by other DHS components, operate with an opaque patchwork of rules that has proved both inadequate to counter abuses and resistant to transparency.

The time has come to rethink DHS intelligence operations and build safeguards that permit the department to provide its leadership with the information it needs while protecting civil rights and civil liberties. This report charts a course for doing so. It focuses initially on I&A, explaining how the office has veered from its counterterrorism mission into tracking social and political movements, often distributing shoddy information and analysis. It then turns to other parts of DHS’s intelligence infrastructure, highlighting significant operations run by CBP and ICE as well as situational awareness initiatives, which have often targeted Americans exercising their First Amendment rights. Finally, it explains why the departmental oversight bodies created by Congress to protect civil rights and liberties consistently fail to prevent intelligence abuses at DHS.

The report concludes with concrete recommendations to end the department’s practice of broadcasting unreliable reports, implement better guardrails to protect civil rights and civil liberties, and create a robust and unified oversight structure. The secretary of homeland security should undertake these changes now, and Congress should codify reforms to ensure that limits on DHS endure across administrations.

Notas al Pie

-

1

By intelligence, we mean the accessing, collecting, retaining, analyzing, or disseminating of information by any component of the Department of Homeland Security (regardless of U.S. Intelligence Community membership) to inform operational, policy, or strategic decisions not directly connected to a predicated criminal investigation, including for purposes such as situational awareness (e.g., to identify and keep abreast of breaking events, including emerging crises); threat detection (e.g., to identify potential threats of violence and terrorism, including by specific individuals); tip and lead generation; civil enforcement of immigration laws; and substantively similar purposes. -

2

Office of Inspector General (hereinafter OIG), The Office of Intelligence and Analysis Needs to Improve Its Open Source Intelligence Reporting, Department of Homeland Security (hereinafter DHS), July 6, 2022, https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2022–07/OIG-22–50-July22.pdf (hereinafter OIG, I&A Needs to Improve Its Open Source Intelligence Reporting); Office of Intelligence and Analysis (hereinafter I&A), Office of Intelligence and Analysis Operations in Portland, DHS, April 20, 2021, https://www.wyden.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/I&A%20and%20OGC%20Portland%20Reports.pdf (hereinafter I&A, I&A Operations in Portland); and Office of the General Counsel (hereinafter OGC), Report on DHS Administrative Review into I&A Open Source Collection and Dissemination Activities During Civil Unrest: Portland, Oregon, June Through July 2020, DHS, January 6, 2021, 13, https://www.wyden.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/I&A%20and%20OGC%20Portland%20Reports.pdf (hereinafter OGC, Administrative Review into I&A Open Source Collection). (Heavily redacted versions of I&A’s and OGC’s reports regarding I&A’s activities in Portland were previously released in 2021. In October 2022, Senator Wyden released new versions of the reports, both of which are compiled in one document. The OGC report begins on page 13 of the compiled document; page numbers cited are the document’s, not the original report’s.) -

3

DHS offices are divided into operational and support components. Operational components are agencies such as CBP and ICE, while support components — sometimes referred to as headquarters offices — provide “specific assistance” to DHS operations, including legal, policy, liaison, and intelligence support. These distinctions are largely technical in nature: support components such as I&A run operations and operational components such as CBP have legal and policy subdivisions. DHS, “Organization of the Department of Homeland Security,” March 31, 2009, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/mgmt/human-resources/mgmt-dir_252–01-organization-of-the-dhs_rev-00.pdf.

Más sobre la Reform Agenda for the Department of Homeland Security series

-

Ending Fusion Center Abuses

The federal government provides state and local intelligence hubs with funding, personnel, and database access — all without adequate oversight. -

Stronger Rules Against Bias

A patchwork of nondiscrimination policies has left the Department of Homeland Security with a profiling problem. Our proposed guidance would close the gaps. -

A Course Correction for Homeland Security

Twenty years after its founding, the Department of Homeland Security struggles to carry out its sweeping counterterrorism mission effectively and equitably.