The redrawing of legislative districts is a process that balances multiple interests and geographic considerations. How map drawers treat counties, the major geographic divisions of states, depends not just on a state’s population but on how state law prioritizes counties in the process.1 In this study, we assess the extent to which a state’s legislative districts respect county lines on the basis of state law requirements to do so.

Our inquiry is designed to measure the efficacy of statutory and constitutional directives related to county preservation in the redistricting process. We refrain from imposing any normative judgment on the practice of splitting or preserving counties. We expect that states with legal directives to keep counties together will do so, that states with no such requirements will tend to split counties more often, and that states in which county preservation is discretionary (typically instructing map drawers to preserve counties where “feasible,” “possible,” or similar) will fall somewhere between these two categories.

Prior to the 1964 U.S. Supreme Court cases Reynolds v. Sims and WMCA, Inc. v. Lomenzo, legislative districts typically contained whole counties, regardless of population differences.2 In Utah, for an illustrative example, a joint resolution in the early 1950s would have allocated 31.6 percent of the state house seats to Salt Lake County (home to 39.9 percent of the state population at the time) and only one seat (or 3.4 percent) in the 29-member state senate.3 In addition, malapportionment across districts — which were infrequently redrawn — would increase over time following population shifts toward urban centers.4

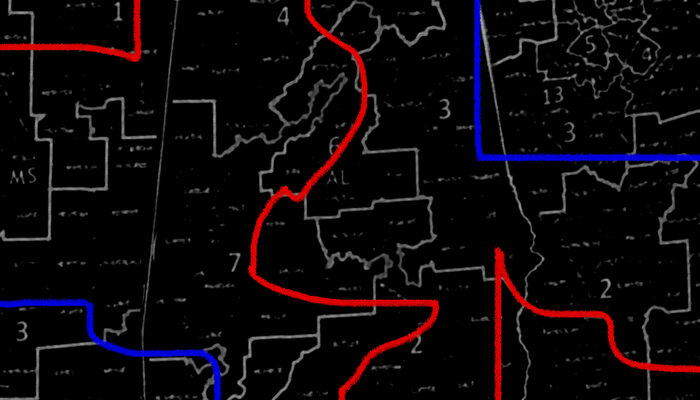

Reynolds held that state legislative districts must be drawn with roughly equal populations. At question was the redistricting process in Alabama, which apportioned one seat in the state house to each county and then distributed the remaining seats in the chamber among the counties on the basis of population; the state senate seats each represented a single county. Similarly, WMCA found that New York State’s apportionment process was unconstitutional because it did not use an equitable population basis.

Through these and other decisions premised on regular redrawing in order to maintain equal population across districts, the Court dispensed with biased redistricting processes across the country.5 What followed was a “redistricting revolution.”6One effect of this new population-equality standard was an increase in the frequency of districts that contained parts of multiple counties.7 How this requirement operates across states with different standards of county preservation has been, until now, unknown.

Here we examine the relationship between the legal requirements related to county preservation and the frequency of counties that are divided across districts.8 Whether states have no requirements, discretionary preservation, or mandatory preservation results in different patterns in state house and senate districts. Mandatory county preservation has kept counties whole at a significantly higher rate than have the other categories in lower chamber districts since 1990, and in upper chamber districts since 2000. At the same time, in upper chamber districts, states with discretionary criteria had fewer county splits, on average, than states with no mention of county preservation in the 1990, 2000, and 2020 redistricting cycles. Contrary to our expectations, however, in lower chamber districts, states with discretionary criteria differed only slightly, if at all, from states with no county preservation requirements.

Endnotes

-

1

We use the term county throughout this article for the sake of consistency. At the same time, we recognize that the subdivisions in Louisiana are referred to as parishes and in Alaska are called boroughs. We also recognize that counties within Connecticut, Rhode Island, and parts of Massachusetts are geographic units that have no separate legal authority. For the purposes of this report, we treat counties primarily as geographic units put through the redistricting process.

-

2

Both decisions were announced on June 15; the Court also rejected legislative plans in Colorado, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia on the same day.

-

3

Frank Jonas and Brad Hainsworth, “Utah,” in Impact of Reapportionment on the Thirteen Western States, ed. Eleanore Bushnell (University of Utah Press, 1970), 268.

-

4

See, e.g., Nathaniel Persily, Thad Kousser, and Patrick Egan, “The Complicated Impact of One Person, One Vote on Political Competition and Representation,” North Carolina Law Review 80, no. 4 (2002): 1343.

-

5

See, e.g., Charles S. Bullock III, Redistricting: The Most Political Activity in America (Rowman & Littlefield, 2010), 30–31, table 2.1 (showing wide differences in district populations in each of the state legislative chambers).

-

6

See, e.g., Gary W. Cox and Jonathan N. Katz, Elbridge Gerry’s Salamander: The Electoral Consequences of the Reapportionment Revolution (Cambridge University Press, 2002), 3 (describing the Court’s intervention in the redistricting process as “arguably the most important change in the practice of American gerrymandering since its invention”). The Supreme Court most recently considered the question of population equality in legislative redistricting in Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, 578 U.S. 253 (2016), finding that deviations of less than 5 percent from the ideal population are permitted if the deviation is caused by legitimate considerations.

-

7

See, e.g., Bullock, Redistricting, 40.

-

8

A related 2009 study found fewer uncontested legislative elections in states with standards protecting political subdivisions within a state. See Richard Forgette, Andrew Garner, and John Winkle, “Do Redistricting Principles and Practices Affect U.S. State Legislative Electoral Competition?,” State Politics and Policy Quarterly 9, no. 2 (Summer 2009): 151–75, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40421634.