The White House Office of Management and Budget has updated the way federal surveys ask about race and ethnicity, the first comprehensive changes to those questions since 1997. This long-awaited overhaul will help the U.S. Census Bureau produce data that is more representative of our increasingly diverse country. But the burden is now on the bureau to implement these changes in ways that will make the 2030 count as easy and inclusive as possible.

The newly announced changes focus on Statistical Policy Directive No. 15, a policy that governs how all federal surveys, including the census, ask about race and ethnicity. The Office of Management and Budget announced three major revisions to the questions.

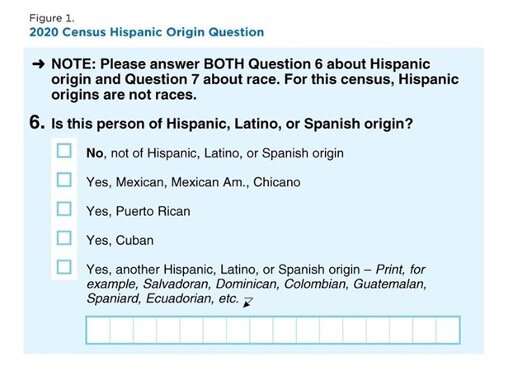

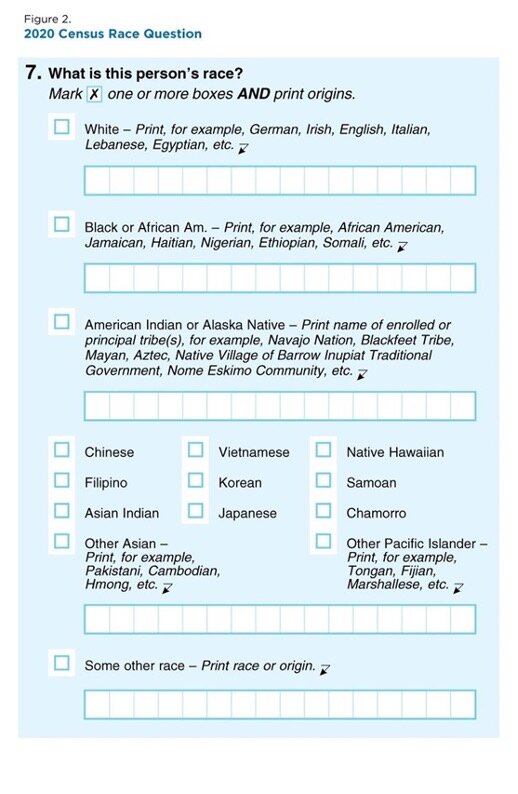

First, the directive requires surveys to ask about race and ethnicity using a single question. Recent censuses asked about these topics using two separate questions. The first asked whether someone was of “Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin.” The second asked respondents to select their race from five primary categories: White; Black or African American; American Indian or Alaskan Native; Asian; or Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. Respondents could also select “Some Other Race.” This is how the questions were displayed on the 2020 Census:

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Many individuals do not think of their race and ethnicity as distinct, so asking about race and ethnicity separately created problems for collecting accurate data about how people self-identify. For example, many Latino people see their primary identity as Latino, so when asked a separate question about their race, they often end up selecting “some other race.”

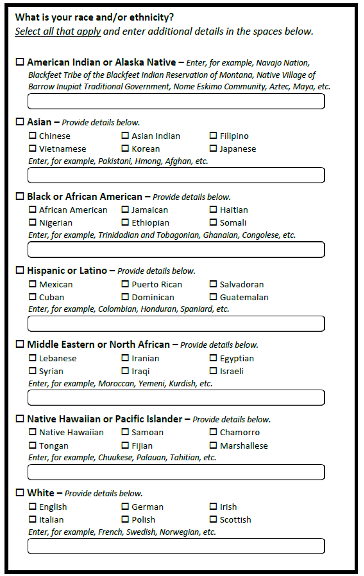

Under the new directive, the 2030 Census form might look something like this example from OMB’s announcement:

Source: White House Office of Management and Budget

Source: White House Office of Management and Budget

Merging the questions and encouraging respondents to select as many categories as apply to them will lead to more detailed self-identification, fewer people selecting “some other race,” and fewer people skipping the question altogether.

Second, surveys will now include “Middle Eastern or North African,” or “MENA,” as a new “minimum” category in the combined race and ethnicity question. The lack of a MENA category in older surveys essentially rendered these communities invisible in federal data and denied Middle Eastern and North African people a collective voice in political representation. This new revision will help remedy this gap in the data.

Third, the directive requires surveys to collect data on race and ethnicity at higher levels of specificity than the “minimum categories.” The older directive allowed, but did not require, agencies to collect information about racial and ethnic subgroup identities. As a result, agencies often did not go beyond collecting the minimum. The lack of detailed data masked important differences that exist across subgroups.

The new policy directive requires federal surveys, when possible, to collect detailed identifications within each race and ethnicity category. It also standardizes subgroup checkboxes and write-in options. Now, for example, a respondent can select “Asian,” and within that category, check a box to indicate that they are “Vietnamese” or write in their identification if it is not reflected in a checkbox (e.g., “Cambodian”).

These revisions will produce data that more accurately reflects how people identify, which is critical as the nation becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, more people identify as more than one race or ethnicity, and migration patterns change. More accurate data, in turn, promises to increase the political, legal, and economic power of communities that have long been undercounted — or even statistically invisible — by giving them a greater share of the political representation and federal funding that are determined by the census numbers.

The job is not finished, however. The Census Bureau will still have to translate the revised directive into a new census form and engage in significant testing and consultation to ensure that the form will produce the best data. And the bureau will have to invest in public outreach and education to ensure that the census is conducted in an inclusive way that makes it easy for everyone living in the country to respond.