In my last post examining the British election and that nation’s laws on money and politics, I fretted. If the United Kingdom, with its already strict rules, its high voter disgust, its ample scandals to justify reform, and a much friendlier constitutional climate can’t tighten the rules, what chance does the United States have?

It could drive me to despair. But I’m not yet ready to learn how to fly a gyrocopter.

Three things give me hope: improved disclosure, intensifying public concern, and sharper policy proposals. I’m only going to discuss disclosure this go round and will turn to the last two points next time.

For many years, the only policy proposals to gain traction in the corridors of political power have turned on transparency. You know the line: “sunshine is the best disinfectant.” Hard to argue with that.

Disclosure provisions have one paramount virtue. They have a shot at implementation, unlike every other proposed remedy (I’m looking at you public campaign financing). Not only are legislatures willing to pass transparency laws, but transparency laws rarely have constitutional infirmities.

There’s a problem though. It doesn’t work.

The disclosure regime has many purported roles: empowering an informed electorate, inhibiting corruption, and enabling enforcement. From the reformers’ standpoint, they all aim in one direction, diminish the role of money in politics.

The vision goes something like this, I suppose: voter sees an attack ad, for example, learns (via disclosure) that the ad’s funders are not a sweet band of citizen grandmas, discounts the attack ad, and then votes for the virtuous—and therefore victorious (?)—candidate. Chastened politician sees that excessive attachment to money means political death and therefore alters his behavior.

Bad news. Money in politics is increasing. Voters are not much better informed. They’re just more disgusted and disengaged. And their solution to the problem is devastating: stopping voting.

(One important exception: disclosure seems to have an appreciable impact on referenda voting and on some corporate behavior.)

Why is disclosure failing and how can we improve it? We need to know if we ever want to deploy one of the few arrows left in the reformers’ quiver.

Today, there’s a virtual campaign finance data gusher thanks to the accomplishments of the reform movement. And we are asking voters and citizens to drink from a fire hydrant.

No wonder disclosure is not having an appreciable impact on money in politics. Reading most campaign finance disclosure has about as much appeal as perusing a drug packaging insert. It’s dense, full of jargon, rarely actionable or comprehensible. Plenty scary though.

There are glimmers of hope. The rise of data journalism and app culture have unleashed a wave of innovation that may help make disclosure more digestible.

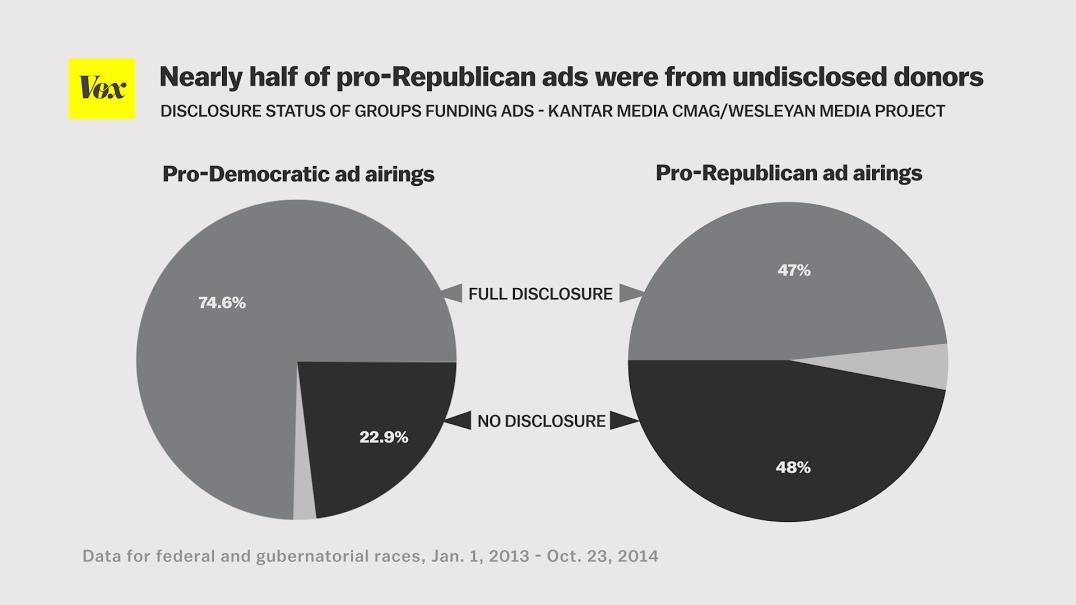

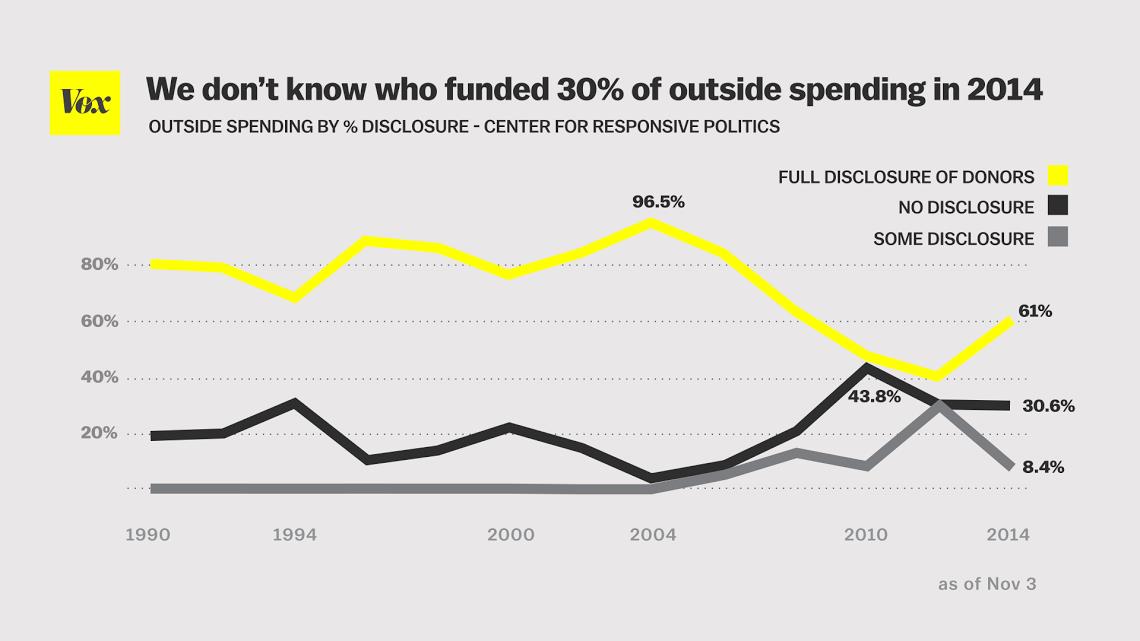

Consider for example the work of one of the leading practitioners of data journalism: Vox. They do great work. Their charts/reporting on the 2014 election provide comprehensible insight into money in politics. Moreover, they provide context and begin to establish baselines.

But if you were a voter who cared about these issues, Vox is not a solution. It does not provide a steady feed of easy-to-find data. The publication only reports on the issues occasionally and usually at very high altitude.

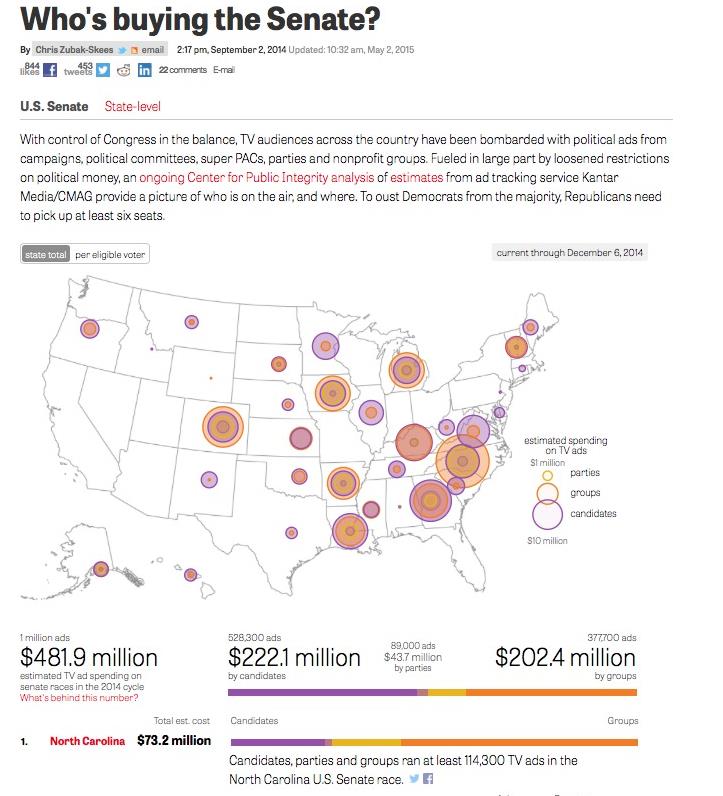

Fortunately, the Pulitzer-prize winning Center for Public Integrity provides a steadier and more granular diet of information. Here’s an example of some of its work:

Both organizations, however, are journalistic. They’re not in the business of motivating voters or directly pushing reform. Consequently, they’re not consistently providing data the way a voter could use to judge candidates or issues. Moreover, their reporting almost always occurs after the election is over.

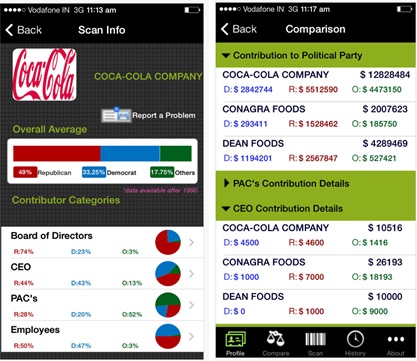

That’s where app culture could step in. Two mobile apps illustrate the promise (and flaws) of providing a steady feed of data to consumers/voters.

One of my favorite apps last year was BuyPartisan. Such a simple premise: scan the barcode of an item you’re interested in buying and then see a wealth of information on the political activity of the manufacturer.

It has issues. It only has data for about 250 companies. And, um, it hasn’t been working recently.

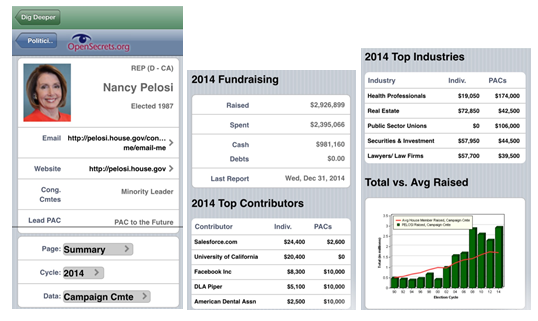

Meanwhile, Open Secrets’ app, Dollarocracy, provides a data gusher but not a lot of context.

I don’t mean to turn this into a tech review. And I’m not highlighting these charts to make a substantive point about Super PAC spending or how much Nancy Pelosi raises from a particular industry. These four items make the point that there’s real promise in how we make disclosure work for the consumer (i.e., the voter).

It’s a start.

The reform movement needs to hone in on the problem and understand its consumer. It needs to stop throwing terabytes of data at voters. It needs to develop a consistent vocabulary and a refined, simple set of metrics to help empower voters. There’s a substantial body of literature on effective disclosure programs. It’s time to dig in.

If the disclosure option is going to be more than magical thinking, it’s time to focus on making it work for voters.

______________

(An aside: astute readers of the charts from Vox will note increased non-disclosure spending. By and large, money is flowing to non-disclosure groups not so much because of privacy concerns but because donations to those groups are unlimited or virtually unlimited. In any event, forcing disclosure from super-PACs is a top priority of the reform movement so my point still stands. It should be. But say super-PACs do start disclosing donors. Then what?)

The views expressed are the author’s own and not necessarily those of the Brennan Center for Justice.

Follow the author’s Tumblr page: Electoral Dysfunction