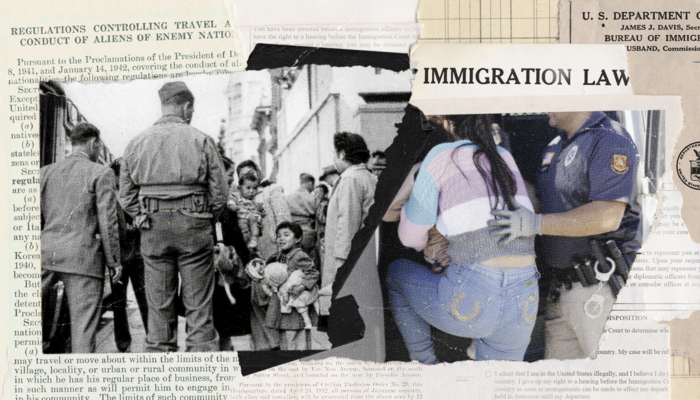

In wartime, the United States must protect its people and territory. Doing so may require actions that might not pass legal or political muster in peacetime, such as the preventive detention of enemy combatants for the duration of the war. But the Alien Enemies Act, an authority that permits summarily detaining and deporting civilians merely on the basis of their ancestry, goes too far and must be reconsidered. Passed in 1798 as a part of the notorious Alien and Sedition Acts, the Alien Enemies Act is a deeply flawed authority with a sordid history.

The law was last invoked in World War II as the legal authority for interning noncitizens of Japanese, German, and Italian descent. Those internments — along with internments during previous wars — were shameful episodes in our nation’s past. The Alien Enemies Act and complementing authorities have allowed presidents to target people on the basis of their identity, not their conduct or the threat they pose to national security. 1 In 1988, when Congress apologized and provided reparations for Japanese internment, it acknowledged that the policy was rooted in “racial prejudice” and “wartime hysteria,” not valid security concerns. 2 Congress would later describe Italian internment as a “fundamental injustice,” 3 and the Department of Justice would recognize that German noncitizens had been targeted “based on their ancestry.” 4

Notwithstanding this widespread condemnation, the Alien Enemies Act was not repealed or amended after the war. Indeed, the law has not been substantially modified since its adoption. If the United States were to declare war in the future, the president would be able to invoke the Alien Enemies Act’s vast detention and deportation power. Worse still, the language of the law is broad enough that a president might be able to wield the authority in peacetime as an end run around the requirements of criminal and immigration law.

This is precisely what politicians and groups who want to restrict immigration propose doing. 5 Most notably, former President Donald Trump has promised to invoke the Alien Enemies Act and wield it as a super-charged deportation authority. 6 Anti-immigration advocates believe that the law allows the president to bypass the substantive and procedural protections for noncitizens, such as the right to seek asylum. 7 And they have sought to weaponize the Alien Enemies Act against immigrants from countries they dislike, particularly Mexico. 8

It is unclear whether the courts would intervene to stop such an abuse. In general, the courts are loath to second-guess presidents’ decisions on sensitive foreign policy and national security matters, such as the appropriate application of wartime authorities. The last time the Alien Enemies Act was challenged, in Ludecke v. Watkins in 1948, the Supreme Court upheld President Harry S. Truman’s extended reliance on the law three years after the end of World War II. 9 The Court reasoned that the question of when a war terminates and wartime authorities expire is too “political” for judicial resolution.

There may, however, be another way for courts to exercise a check on Alien Enemies Act invocations. Summary detentions and deportations under the law conflict with contemporary understandings of equal protection and due process. These understandings developed as a part of the civil rights revolution that remade the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments — well after the law was last invoked. Reconceived, equal protection and due process led courts and the public to reject Korematsu v. United States, the 1944 case that upheld Japanese internment, as well as other judicial precedents upholding discrimination against noncitizens based on their ancestry. 10 Because equal protection and due process challenges would be legal, not political, in nature, the courts would have to resolve these challenges on the merits instead of categorically deferring to the president.

Of course, the surest way to prevent abuse of the Alien Enemies Act — and to address its problematic reliance on ancestry — is through preemptive repeal. For decades, lawmakers on Capitol Hill have proposed measures to repeal or reconsider the Alien Enemies Act as a symbolic reparation for the internment of Japanese, German, and Italian noncitizens during World War II. 11 Repealing the law would no longer be merely symbolic, given recent proposals to use it for mass deportations in peacetime. Indeed, repeal is crucial to preventing presidential overreach and safeguarding civil liberties.

This report offers a framework for overturning or substantially modifying the Alien Enemies Act, through either litigation or legislation. Part I examines the Alien Enemies Act’s text, history, and potential for abuse. Part II explores possible equal protection and due process challenges to the law’s constitutionality. Part III provides an overview of existing alternatives to the Alien Enemies Act that can more appropriately safeguard the nation against espionage, sabotage, and other malign activities in wartime.

An earlier version of this report described the Alien Enemies Act as the authority for interning “immigrants” of Japanese, German, and Italian descent. The report was updated on October 16, 2024, to clarify that the law applied only to immigrants who had not become citizens of the United States.

Endnotes

-

1

The Alien Enemies Act does not apply to U.S. citizens, irrespective of whether they are the natives or dual citizens of a foreign belligerent. Japanese internment, however, targeted both U.S. citizens and noncitizens of Japanese descent. Insofar as the Roosevelt administration interned U.S. citizens of Japanese descent, it relied on World War II–era executive orders, military orders, and legislation — specifically the Act to Provide a Penalty for Violation of Restrictions or Orders with Respect to Persons Entering, Remaining in, Leaving, or Committing Any Act in Military Areas or Zones. Pub. L. 77–503, 56 Stat. 173 (1942), https://govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/56/STATUTE-56-Pg173b.pdf. These World War II–era authorities are no longer on the books.

-

2

Civil Liberties Act of 1988, Pub. L. 100–383, 102 Stat. 903 (1988), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-102/pdf/STATUTE-102-Pg903.pdf. The 1988 reparations law covers not only U.S. citizens of Japanese descent but also noncitizen internees. It apologizes for detentions undertaken pursuant to executive and military orders, World War II–era laws, and also presidential proclamations — a category that includes President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s invocation of the Alien Enemies Act.

-

3

Wartime Violation of Italian American Civil Liberties Act, Pub. L. 106–451, 114 Stat. 1947 (2000), https://www.congress.gov/106/plaws/publ451/PLAW-106publ451.pdf.

-

4

U.S. Department of Justice, “A Review of the Restrictions on Persons of Italian Ancestry During World War II,” November 15,

2001, 15, https://www.tunacanyon.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/A-Review-of-the-Restrictions-on-Persons-of-Italian-Ancestry-During-World-War-II-2.pdf. -

5

American Presidency Project, “2024 GOP Platform Make America Great Again!,” University of California, Santa Barbara, accessed August 14, 2024, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/2024-republican-party-platform; and George Fishman, “The 225-Year-Old ‘Alien Enemies Act’ Needs to Come Out of Retirement,” Center for Immigration Studies, October 10, 2023, https://cis.org/Report/225yearold-Alien-Enemies-Act-Needs-Come-Out-Retirement.

-

6

Asawin Suebsaeng and Adam Rawnsley, “Trump’s Bonkers Plan to Weaponize an Archaic Law for Mass Deportations,” Rolling Stone, January 8, 2024, https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-features/trump-archaic-law-mass-deportations-1234941671/; and Donald Trump, “This Is How I Will End Joe Biden’s Border Disaster

on Day One,” Des Moines Register, January 3, 2024, https://www.desmoinesregister.com/story/opinion/columnists/caucus/2024/01/03/donald-trump-joe-biden-border-disaster/72093156007/. -

7

Ed Pilkington, “Mass Deportations, Detention Camps, Troops on the Street: Trump Spells Out Migrant Plan,” Guardian, May 3, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/article/2024/may/03/trump-mass-deportations-detention-camps-military-migrants.

-

8

Fishman, “The 225-Year-Old ‘Alien Enemies Act’”; George Fishman, “Iran and the Alien Enemies Act,” Center for Immigration Studies, May 7, 2024, https://cis.org/Report/Iran-and-Alien-Enemies-Act; and Suebsaeng and Rawnsley, “Trump’s Bonkers Plan.”

-

9

Ludecke v. Watkins, 335 U.S. 160 (1948).

-

10

Adarand Constructors v. Pena, 515 U.S. 200 (1995); Jamal Greene, “The Anticanon,” Harvard Law Review 125, no. 2 (December 2011), https://harvardlawreview.org/print/vol-125/the-anticanon/; and Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944). Also see, e.g., Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948); and Fujii v. California, 38 Cal.2d 718 (C.A. 1952).

-

11

Neighbors Not Enemies Act, S. 3690, 117th Cong. (2022), https://www.congress.gov/117/bills/s3690/BILLS-117s3690is.pdf; and Wartime Treatment Study Act, S. 1691, 108th Cong. (2003), https://www.congress.gov/108/bills/s1691/BILLS-108s1691rs.pdf.