Introduction

This report was updated in March 2020 to reflect Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s new policy concerning border searches of electronic devices.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is rapidly expanding its collection of social media information and using it to evaluate the security risks posed by foreign and American travelers. This year marks a major expansion. The visa applications vetted by DHS will include social media handles that the State Department is set to collect from some 15 million travelers per year. 1 Social media can provide a vast trove of information about individuals, including their personal preferences, political and religious views, physical and mental health, and the identity of their friends and family. But it is susceptible to misinterpretation, and wholesale monitoring of social media creates serious risks to privacy and free speech. Moreover, despite the rush to implement these programs, there is scant evidence that they actually meet the goals for which they are deployed.

While officials regularly testify before Congress to highlight some of the ways in which DHS is using social media, they rarely give a full picture or discuss either the effectiveness of such programs or their risks. The extent to which DHS exploits social media information is buried in jargon-filled notices about changes to document storage systems that impart only the vaguest outlines of the underlying activities.

To fill this gap, this report seeks to map out the department’s collection, use, and sharing of social media information by piecing together press reports, information obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests, Privacy Impact Assessments, 2 System of Records Notices (SORNs), 3 departmental handbooks, government contracts, and other publicly available documents.

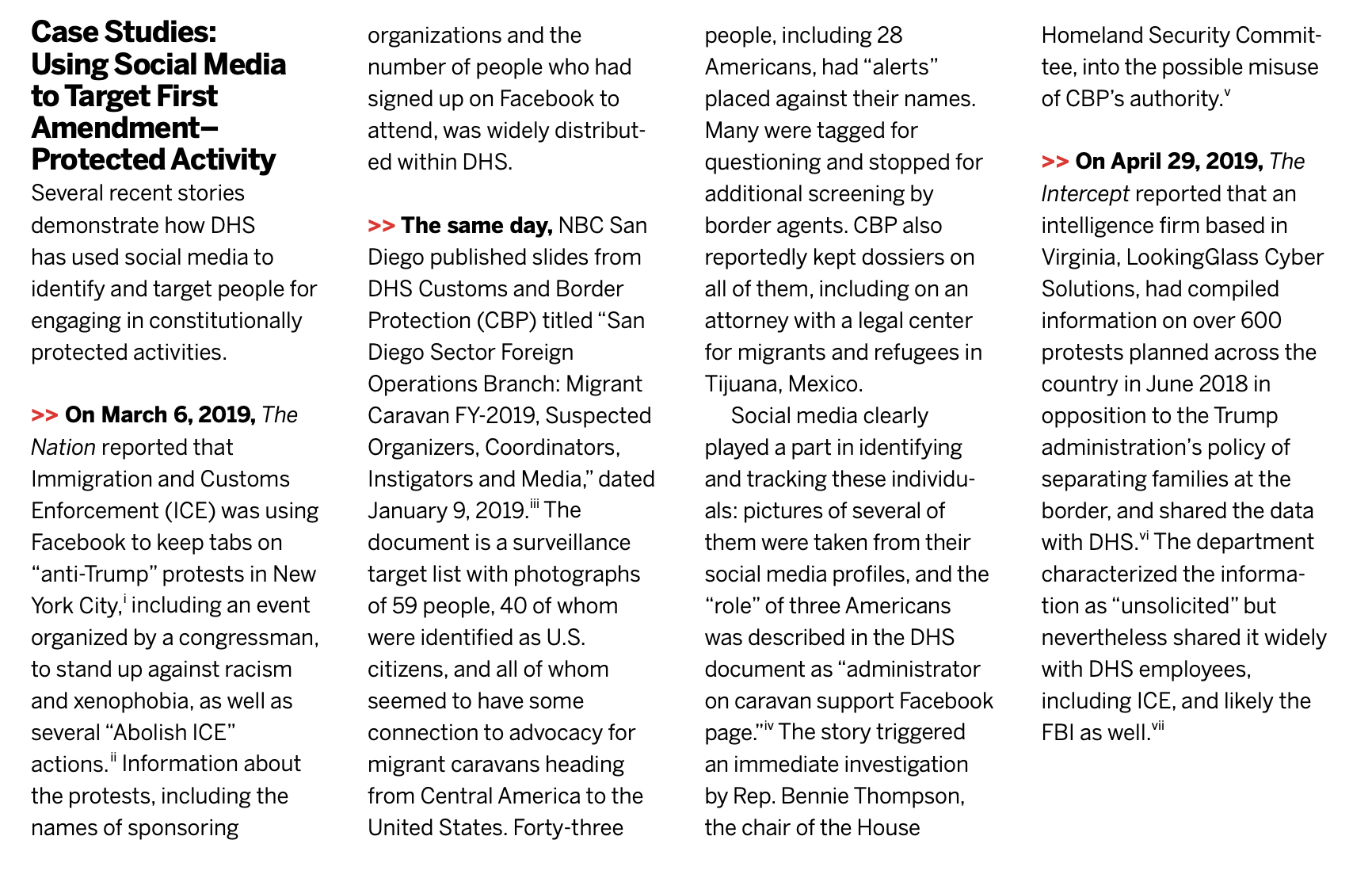

In light of DHS’s expanding use of social media monitoring programs, understanding the ways in which the department exploits social media is critical. Personal information gleaned from social media posts has been used to target dissent and subject religious and ethnic minorities to enhanced vetting and surveillance. Some DHS programs are targeted at travelers, both Americans and those from other countries. And while the department’s immigration vetting programs ostensibly target foreigners, they also sweep up information about American friends, family members, and business associates, either deliberately or as a consequence of their broad scope.

Muslims are particularly vulnerable to targeting. According to a 2011 Pew survey (which was followed by a similar survey in 2017), more than a third of Muslim Americans who traveled by air reported that they had been singled out by airport security for their faith, suggesting a connection between being a devout Muslim and engaging in terrorism that has long been debunked. 4 A legal challenge to this practice is pending. 5 According to government documents, one of the plaintiffs, Hassan Shibly, executive director of the Florida chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, was pulled aside for secondary screening at the border at least 20 times from 2004 to 2011. 6 He says he was asked questions like “Are you part of any Islamic tribes?” and “Do you attend a particular mosque?” 7 Shibly’s story is hardly unique. 8

Concerns about such screenings are even more urgent under the Trump administration, which has made excluding Muslims a centerpiece of its immigration agenda through policies such as the Muslim ban and implementation of “extreme vetting” for refugee and visa applicants, primarily those from the Muslim world. 9 A leaked DHS draft report from 2018 suggests that the administration is considering tagging young Muslim men as “at-risk persons” who should be subjected to intensive screening and ongoing monitoring. 10 If implemented, such a policy would affect hundreds of thousands of people. 11 DHS’s social media monitoring pilot programs seem to have focused in large part on Muslims: at least two targeted Syrian refugees, one targeted both Syrian and Iraqi refugees, and the analytical tool used in at least two pilots was tailored to Arabic speakers. 12

More generally, social media monitoring — like other forms of surveillance — will impact what people say online, leading to self-censorship of people applying for visas as well as their family members and friends. The deleterious effect of surveillance on free speech has been well documented in empirical research; one recent study found that awareness or fear of government surveillance of the internet had a substantial chilling effect among both U.S. Muslims and broader U.S. samples of internet users. 13 Even people who said they had nothing to hide were highly likely to self-censor online when they knew the government was watching. 14 As Justice Sonia Sotomayor warned in a 2012 Supreme Court case challenging the warrantless use of GPS tracking technology, “[a]wareness that the Government may be watching chills associational and expressive freedoms. And the Government’s unrestrained power to assemble data that reveals private aspects of identity is susceptible to abuse.” 15

DHS’s pilot programs for monitoring social media have been notably unsuccessful in identifying threats to national security. 16 In 2016, DHS piloted several social media monitoring programs, one run by ICE and five by United States Customs and Immigration Services (USCIS). 17 A February 2017 DHS inspector general audit of these pilot programs found that the department had not measured their effectiveness, rendering them an inadequate basis on which to build broader initiatives. 18

Even more damning are USCIS’s own evaluations of the programs, which showed them to be largely ineffective. According to a brief prepared by DHS for the incoming administration at the end of 2016, for three out of the four programs used to vet refugees, “the information in the accounts did not yield clear, articulable links to national security concerns, even for those applicants who were found to pose a potential national security threat based on other security screening results.” 19 The brief does show that USCIS complied with its own rules, which prohibit denying benefits solely on the basis of public-source information — such as that derived from social media — due to “its inherent lack of data integrity.” 20 The department reviewed 1,500 immigration benefits cases and found that none were denied “solely or primarily because of information uncovered through social media vetting.” 21 But this information provided scant insights in any event: out of the 12,000 refugee applicants and 1,500 immigration benefit applicants screened, USCIS found social media information helpful only in “a small number of cases,” where it “had a limited impact on the processing of those cases — specifically in developing additional lines of inquiry.” 22

In fact, a key takeaway from the pilot programs was that they were unable to reliably match social media accounts to the individual being vetted, and even where the correct accounts were found, it was hard to determine “with any level of certainty” the “authenticity, veracity, [or] social context” of the data, as well as whether there were “indicators of fraud, public safety, or national security concern.” 23 The brief explicitly questioned the overall value of the programs, noting that dedicating personnel “to mass social media screening diverts them away from conducting the more targeted enhanced vetting they are well trained and equipped to do.” 24

The difficulties faced by DHS personnel are hardly surprising; attempts to make judgments based on social media are inevitably plagued by problems of interpretation. 25 In 2012, for example, a British national was denied entry at a Los Angeles airport when DHS agents misinterpreted his posting on Twitter that he was going to “destroy America” — slang for partying — and “dig up Marilyn Monroe’s grave” — a joking reference to a television show. 26 As the USCIS pilot programs demonstrate, interpretation is even harder when the language used is not English and the cultural context is unfamiliar. If the State Department’s current plans to undertake social media screening for 15 million travelers are implemented, government agencies will have to be able to understand the languages (more than 7,000) and cultural norms of 193 countries. 27

Nonverbal communications on social media pose yet another set of challenges. As the Brennan Center and 34 other civil rights and civil liberties organizations pointed out in a May 2017 letter to the State Department:

“If a Facebook user posts an article about the FBI persuading young, isolated Muslims to make statements in support of ISIS, and another user ‘loves’ the article, is he sending appreciation that the article was posted, signaling support for the FBI’s practices, or sending love to a friend whose family has been affected?” 28

All of these difficulties, already substantial, are compounded when the process of reviewing posts is automated. Obviously, using simple keyword searches in an effort to identify threats would be useless because they would return an overwhelming number of results, many of them irrelevant. One American police department learned this lesson the hard way when efforts to unearth bomb threats online instead turned up references to “bomb” (i.e., excellent) pizza. 29 Natural language processing, the tool used to judge the meaning of text, is not nearly accurate enough to do the job either. Studies show that the highest accuracy rate achieved by these tools is around 80 percent, with top-rated tools generally achieving 70–75 percent accuracy. 30 This means that 20–30 percent of posts analyzed through natural language processing would be misinterpreted.

Algorithmic tone and sentiment analysis, which senior DHS officials have suggested is being used to analyze social media, is even less accurate. 31 A recent study concluded that it could make accurate predictions of political ideology based on users’ Twitter posts only 27 percent of the time, observing that the predictive exercise was “harder and more nuanced than previously reported.” 32 Accuracy plummets even further when the speech being analyzed is not standard English. 33 Indeed, even English speakers using nonstandard dialects or lingo may be misidentified by automated tools as speaking in a different language. One tool flagged posts in English by black and Hispanic users — like “Bored af den my phone finna die!!!!” (which can be loosely translated as “I’m bored as f*** and then my phone is going to die”) — as Danish with 99.9 percent confidence. 34

Crucially — as the USCIS pilot programs discussed above demonstrated — algorithms are generally incapable of making the types of subjective evaluations that are required in many DHS immigration programs, such as whether someone poses a threat to public safety or national security or whether certain information is “derogatory.” Moreover, because these types of threats are difficult to define and measure, makers of algorithms will turn to “proxies” that are more easily observed. But there is a risk that the proxies will bear little or no relationship to the task and that they will instead reflect stereotypes and assumptions. The questioning of Muslim travelers about their religious practice as a means of judging the threat they pose shows that unfounded and biased assumptions are already entrenched at DHS. It would be easy enough to embed them in an algorithm.

Despite these serious shortcomings in terms of effectiveness and critics’ well-founded concerns about the potential for targeting certain political views and faiths, DHS is proceeding with programs for monitoring social media. 35 The department’s attitude is perhaps best summed up by an ICE official who acknowledged that while they had not yet found anything on social media, “you never know, the day may come when social media will actually find someone that wasn’t in the government systems we check.” 36

The consequences of allowing these types of programs to continue unchecked are too grave to ignore. In addition to responding to particular cases of abuse, Congress needs to fully address the risks of social media monitoring in immigration decisions. This requires understanding the overall system by which DHS collects this type of information, how it is used, how it is shared with other agencies, and how it is retained – often for decades – in government databases. Accordingly, this paper maps social media exploitation by the four parts of DHS that are most central to immigration: Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). It also examines DHS’s cooperation with the Department of State, which plays a key role in immigration vetting.

Notas al Pie

-

1

U.S. Department of State, “60-Day Notice of Proposed Information Collection: Application for Nonimmigrant Visa,” 83 Fed. Reg. 13807, 13808 (March 30, 2018), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=DOS-2018–0002–0001; Department of State, “60-Day Notice of Proposed Information Collection: Application for Immigrant Visa and Alien Registration,” 83 Fed. Reg. 13806, 13807 (March 30, 2018), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=DOS-2018–0003–0001; this proposed collection was approved on April 11, 2019. OMB, Notice of Office of Management and Budget Action, “Online Application for Nonimmigrant Visa,” April 11, 2019, https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/DownloadNOA?requestID=292517; OMB, Notice of Office of Management and Budget Action, “Electronic Application for Immigrant Visa and Alien Registration,” April 11, 2019, https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/PRAViewICR?ref_nbr=201808–1405–004. See also Brennan Center for Justice et al., Comments to Department of State, “Re: DS-160 and DS-156, Application for Nonimmigrant Visa, OMB Control No. 1405–0182; DS-260, Electronic Application for Immigrant Visa and Alien Registration, OMB Control No. 1405–185,” May 29, 2018, https://www.scribd.com/document/380580064/Brennan-Center-Urges-State-Department-to-Abandon-the-Collection-of-Social-Media-and-Other-Data-from-Visa-Applicants. Department of State visa applications are vetted using DHS’s Automated Targeting System (ATS). DHS, Privacy Impact Assessment Update for the Automated Targeting System, DHS/CBP/PIA-006(e), January 13, 2017 (hereinafter ATS 2017 PIA), 8–9, 35, 59–60, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/privacy-pia-cbp006-ats-december2018.pdf. The social media identifiers that the State Department collects via visa applications will be stored in the department’s Consolidated Consular Database, which is ingested into ATS and becomes available to DHS personnel. ATS 2017 PIA, 3, 8–9, 12. For more on DHS involvement in State Department visa vetting, see infra text accompanying notes 118–131. -

2

Section 208 of the E-Government Act of 2002 requires privacy impact assessments (PIAs) for all information technology that uses, maintains, or disseminates personally identifiable information or when initiating a new collection of personally identifiable information from 10 or more individuals in the public. E-Government Act of 2002, PL 107–347, December 17, 2002, 116 Stat 2899, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-107publ347/pdf/PLAW-107publ347.pdf; DHS, “Privacy Compliance,” accessed April 25, 2019, https://www.dhs.gov/compliance. DHS is required to publish or update existing privacy impact assessments when developing or procuring any new program or system that will handle or collect personally identifiable information; for budget submissions to the Office of Management and Budget that affect personally identifiable information; with pilot tests that affect personally identifiable information; when developing program or system revisions that affect personally identifiable information; or when issuing a new or updated rulemaking that involves the collection, use, and maintenance of personally identifiable information. Because revisions that affect personally identifiable information are common, DHS often issues multiple, updated privacy impact assessments for a single program or system. -

3

A System of Records Notice (SORN) is required whenever the department has a “system of records” — a group of records from which information is retrieved by a personal identifier, such as one’s name. SORNs, formal notices to the public published in the Federal Register, identify the purpose for which personally identifiable information is collected, what type of information is collected and from whom, how personally identifiable information is shared externally (routine uses), and how to access and correct any personally identifiable information maintained by DHS. DHS, “Privacy Compliance.” -

4

Pew Research Center, Muslim Americans: No Signs of Growth in Alienation or Support for Extremism, August 30, 2011, 108, http://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/legacy-pdf/Muslim-American-Report-10–02–12-fix.pdf (41 percent of American Muslims surveyed said they had not taken a flight in the past year, and 21 percent of those surveyed had been singled out by airport security, meaning that almost 36 percent of those surveyed who had taken a flight were singled out at security); Pew Research Center, U.S. Muslims Concerned About Their Place in Society, but Continue to Believe in the American Dream, July 26, 2017, 13, https://www.pewforum.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2017/07/U.S.-MUSLIMS-FULL-REPORT-with-population-update-v2.pdf (reporting that 18 percent of American Muslims were singled out at airport security in the previous year, but not indicating the percentage of American Muslims who did not travel by air in the previous year); Faiza Patel, Rethinking Radicalization, Brennan Center for Justice, March 2011, https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/RethinkingRadicalization.pdf; Marc Sageman, Misunderstanding Terrorism (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016); Jamie Bartless, Jonathan Birdwell, and Michael King, The Edge of Violence, Demos, December 2010, https://www.demos.co.uk/files/Edge_of_Violence_-_full_-_web.pdf?1291806916. -

5

Cherri v. Mueller, 951 F. Supp. 2d 918 (E.D. Mich. 2013). -

6

Kari Huus, “Muslim Travelers Say They’re Still Saddled With 9/11 Baggage,” NBC News, September 9, 2011, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/44334738/ns/us_news-9_11_ten_years_later/t/muslim-travelers-say-theyre-still-saddled-baggage/#.XH61NcBKhpg. -

7

ACLU and Muslim Advocates to DHS Inspector General Richard L. Skinner, December 16, 2010, https://www.aclu.org/letter/aclu-and-muslim-advocates-letter-department-homeland-security-inspector-general-richard. -

8

See Amanda Holpuch and Ashifa Kassam, “Canadian Muslim Grilled About Her Faith and View on Trump at U.S. Border Stop,” Guardian, February 10, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/feb/10/canadian-muslim-us-border-questioning; Emma Graham-Harrison, “US Border Agents Ask Muhammad Ali’s Son, ‘Are You a Muslim?’ ” Guardian, February 25, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/feb/25/muhammad-ali-son-detained-questioned-us-border-control; ACLU and Muslim Advocates to Skinner (highlighting the experiences of four other Muslim Americans who faced persistent religious questioning by CBP). See also Pew Research Center, Muslim Americans, 2. -

9

See Faiza Patel and Harsha Panduranga, “Trump’s Latest Half-Baked Muslim Ban,” Daily Beast, June 12, 2017, https://www.thedailybeast.com/trumps-latest-half-baked-muslim-ban (noting that the administration’s “extreme vetting” rules are aimed at the same pool of people as the Muslim ban); Harsha Panduranga, Faiza Patel, and Michael W. Price, Extreme Vetting and the Muslim Ban, Brennan Center for Justice, 2017, 2, 16, https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/publications/extreme_vetting_full_10.2_0.pdf. Brennan Center for Justice et al., Comments to Department of State, “Re: DS-160 and DS-156, Application for Nonimmigrant Visa, OMB Control No. 1405–0182; DS-260, Electronic Application for Immigrant Visa and Alien Registration, OMB Control No. 1405–185,” 7–8 (noting that the State Department’s proposed collection of social media information from visa applicants would disproportionately burden Muslims). See infra note 120 and text accompanying notes 118–131. -

10

DHS, “Demographic Profile of Perpetrators of Terrorist Attacks in the United States Since September 2001 Attacks Reveals Screening and Vetting Implications,” 2018, https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/4366754/Text-of-CPB-Report.pdf. The draft report, published by Foreign Policy, was produced at the request of the commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to “inform United States foreign visitor screening, immigrant vetting and on-going evaluations of United States-based individuals who might have a higher risk of becoming radicalized and conducting a violent attack.” It examined 29 individuals who, according to CBP, carried out terrorist incidents in the United States “driven by radical Sunni Islamist militancy.” Given the data set the report focused on, it unsurprisingly found that this cohort of people were mostly young, Muslim, and male. Ignoring the fact that hundreds of thousands of people who meet this description travel to the United States each year, CBP concluded that these characteristics provided a “baseline to identify at-risk persons.” In fact, CBP even suggested that in addition to initial screenings, this enormous group of people should be “continuously evaluate[d],” for example when they applied for visa renewals or immigration benefits. Ibid., 4. -

11

The Department of State issued more than 900,000 immigrant and nonimmigrant visas to individuals from Muslim-majority countries in FY 2018, which likely included hundreds of thousands of young Muslim men. See Department of State, Report of the Visa Office 2018, Table III and Table XVIII, https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/legal/visa-law0/visa-statistics/annual-reports/report-of-the-visa-office-2018.html. -

12

See infra text accompanying note 428. -

13

Elizabeth Stoycheff et al., “Privacy and the Panopticon: Online Mass Surveillance’s Deterrence and Chilling Effects,” New Media & Society 21, no. 3 (2018): 1–18, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1461444818801317. See also Dawinder S. Sidhu, “The Chilling Effect of Government Surveillance Programs on the Use of the Internet by Muslim-Americans,” University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender and Class 7, no. 2 (2007), https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/56358880.pdf. -

14

Elizabeth Stoycheff, “Under Surveillance: Examining Facebook’s Spiral of Silence Effects in the Wake of NSA Internet Monitoring,” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 93, no. 2 (2016): 296–311, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1077699016630255. Similarly, in a survey of a representative sample of U.S. internet users, 62 percent reported that they would be much less or somewhat less likely to touch on certain topics if the government was watching, with 78 percent of respondents agreeing that they would be more cautious about what they said online. J. W. Penney, “Internet Surveillance, Regulation, and Chilling Effects Online: A Comparative Case Study,” Internet Policy Review 6, no. 2 (2017), https://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/internet-surveillance-regulation-and-chilling-effects-online-comparative-case. Another study measured how internet users in 11 countries reacted when they found out that DHS was keeping track of searches of terms that it regarded as suspicious, such as “state of emergency” and “drug war.” Users were less likely to search using terms that they believed might get them in trouble with the U.S. government. Alex Marthews and Catherine Tucker, “Government Surveillance and Internet Search Behavior,” February 17, 2017, https://ssrn.com/abstract=2412564. The study analyzed the search prevalence of select keywords compiled by the Media Monitoring Capability section of the National Operations Center of DHS. The list of keywords was publicized in 2012 as “suspicious” selectors that might lead to a particular user being flagged for analysis by the National Security Agency (NSA). See DHS, National Operations Center Media Monitoring Capability, “Analyst’s Desktop Binder,” 20, https://epic.org/foia/epic-v-dhs-media-monitoring/Analyst-Desktop-Binder-REDACTED.pdf. The authors later expanded their study to 41 countries and found that, for terms that users believed might get them in trouble with the U.S. government, the search prevalence fell by about 4 percent across the countries studied. Alex Marthews and Catherine Tucker, “The Impact of Online Surveillance on Behavior” in The Cambridge Handbook of Surveillance Law, ed. David Gray and Stephen E. Henderson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 446. See also Human Rights Watch, With Liberty to Monitor All: How Large-Scale U.S. Surveillance Is Harming Journalism, Law, and American Democracy, July 28, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/07/28/liberty-monitor-all/how-large-scale-us-surveillance-harming-journalism-law-and; PEN America Center, Chilling Effects: NSA Surveillance Drives U.S. Writers to Self-Censor, November 12, 2013, https://pen.org/sites/default/files/2014–08–01_Full%20Report_Chilling%20Effects%20w%20Color%20cover-UPDATED.pdf (finding that 28 percent of writers reported “curtailed social media activities” in response to the Snowden revelations, 24 percent reported that they “deliberately avoided certain topics in phone or email conversations,” and 16 percent reported that they “avoided writing or speaking about a particular topic”). -

15

United States v. Jones, 565 U.S. 400 (2012) (Sotomayor, J., concurring). -

16

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Social Media,” in U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Briefing Book, (hereinafter USCIS Briefing Book) 181, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/USCIS%20Presidential%20Transition%20Records.pdf. -

17

Office of Inspector General, DHS’ Pilots for Social Media Screening Need Increased Rigor to Ensure Scalability and Long-term Success (Redacted), February 27, 2017, https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2017/OIG-17–40-Feb17.pdf. -

18

Ibid. In a letter to the inspector general sent in response to the investigation, which was included in the publicly available report, DHS personnel noted that CBP also conducted a pilot program, with another soon to be initiated as of December 2016, but there is no publicly available information about either. Ibid., 7. -

19

USCIS Briefing Book, 181. -

20

Ibid., 183; DHS, Privacy Impact Assessment for the Fraud Detection and National Security Directorate, DHS/USCIS/PIA-013–01, December 16, 2014 (hereinafter FDNS 2014 PIA), 14, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/privacy-pia-uscis-fdns-november2016_0.pdf. -

21

USCIS Briefing Book, 183. -

22

Ibid., 183. -

23

Ibid., 183. Additional problems identified were the fact that refugee applicants had only a “minimal presence” on social media platforms accessible through social media monitoring programs and that the content was often not in English. Ibid., 181, 184. -

24

Ibid., 184. -

25

See Alexandra Olteanu et al., “Social Data: Biases, Methodological Pitfalls, and Ethical Boundaries,” December 20, 2016, http://kiciman.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/SSRN-id2886526.pdf; Brennan Center for Justice et al., Comments to Department of State Regarding “Notice of Information Collection Under OMB Emergency Review: Supplemental Questions for Visa Applicants,” May 18, 2017, https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/analysis/State%20Dept%20Information%20Collection%20Comments%20-%2051817_3.pdf. -

26

See J. David Goodman, “Travelers Say They Were Denied Entry to U.S. for Twitter Jokes,” New York Times, January 30, 2012, https://thelede.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/01/30/travelers-say-they-were-denied-entry-to-u-s-for-twitter-jokes/. FBI agents and even courts have erroneously interpreted tweets of rap lyrics as threatening messages. See, for example, Natasha Lennard, “The Way Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s Tweets Are Being Used in the Boston Bombing Trial Is Very Dangerous,” Fusion, March 12, 2015, http://fusion.net/story/102297/the-use-of-dzhokhar-tsarnaevs-tweets-inthe-bostonbombing-trial-is-very-dangerous/; a Pennsylvania man was even sentenced to more than three years in prison for rap-style lyrics he posted to Facebook. The Supreme Court reversed the conviction in 2015. United States v. Elonis, 2011 WL 5024284 (E.D. Pa. Oct. 20, 2011), aff’d, 730 F.3d 321 (3d Cir. 2013), rev’d and remanded, 135 S. Ct. 2001 (2015), and aff’d, 841 F.3d 589 (3d Cir. 2016). -

27

The total number of world languages is disputed. One widely cited estimate is that there are about 7,111 living languages, of which 3,995 have a developed writing system. These numbers are based on the definition of language (as opposed to dialect) as a speech variety that is not mutually intelligible with other speech varieties. See David M. Eberhard, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.), Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 22nd ed. (Dallas, Texas: SIL International, 2019), https://www.ethnologue.com/enterprise-faq/how-many-languages-world-are-unwritten-0. The Department of State issues nonimmigrant visas to individuals from every country in the world annually. See Department of State, Report of the Visa Office 2018, Table XVIII: “Nonimmigrant Visas Issued by Nationality (Including Border Crossing Cards) Fiscal Year 2009–2018,” https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/visas/Statistics/AnnualReports/FY2018AnnualReport/FY18AnnualReport%20-%20TableXVIII.pdf. -

28

Brennan Center for Justice et al., Comments to Department of State Regarding “Notice of Information Collection Under OMB Emergency Review,” 4–5. -

29

Ben Conarck, “Sheriff’s Office’s Social Media Tool Regularly Yielded False Alarms,” Jacksonville, May 30, 2017, https://www.jacksonville.com/news/public-safety/metro/2017–05–30/sheriff-s-office-s-social-media-tool-regularly-yielded-false. -

30

Natasha Duarte, Emma Llanso, and Anna Loup, Mixed Messages? The Limits of Automated Social Media Content Analysis, Center for Democracy and Technology, 2017, 5, https://cdt.org/files/2017/11/Mixed-Messages-Paper.pdf; Shervin Malmasi and Marcos Zampieri, “Challenges in Discriminating Profanity From Hate Speech,” Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence 30, no. 2 (2018): 1–16, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1803.05495.pdf (reporting an 80 percent accuracy rate in distinguishing general profanity from hate speech in social media). Irene Kwok and Yuzhou Wang, “Locate the Hate: Detecting Tweets Against Blacks,” Proceedings of the 27th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2013), https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/db55/11e90b2f4d650067ebf934294617eff81eca.pdf (finding an average 76 percent accuracy rate classifying hate speech on Twitter); Bo Han, “Improving the Utility of Social Media With Natural Language Processing” (PhD dissertation, University of Melbourne, February 2014), https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/fd66/afb9d50c4770a529e7d125809053586b28dd.pdf (showing that natural language processing tools used to normalize “out-of-vocabulary” words, such as slang and abbreviations common on social media, into standard English achieved a 71.2 percent accuracy rate). In fact, accuracy itself is a somewhat slippery concept in these studies — it measures whether the tool came to the same conclusion that a human would have, but it does not take into account the possibility of human error or subjectivity. Duarte, Llanso, and Loup, Mixed Messages? 5, 17–18. -

31

See Aaron Cantú and George Joseph, “Trump’s Border Security May Search Your Social Media by ‘Tone,’ ” The Nation, August 23, 2017, https://www.thenation.com/article/trumps-border-security-may-search-your-social-media-by-tone/ (noting that a senior DHS official touted the department’s capacity to search its data sets, including social media data, “by tone”). Ahmed Abbasi, Ammar Hassan, and Milan Dhar, “Benchmarking Twitter Sentiment Analysis Tools,” Proceedings of the Ninth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (2014), https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ammar_Hassan6/publication/273000042_Benchmarking_Twitter_Sentiment_Analysis_Tools/links/54f484d70cf2ba6150634593.pdf (finding that the best-performing sentiment analysis tools attain overall accuracies between 65 percent and 71 percent on average, while many low-performing tools yield accuracies below 50 percent); Mark Cieliebak et al., “A Twitter Corpus and Benchmark Resources for German Sentiment Analysis,” Proceedings of the Fifth International Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Social Media (2017): 49, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a050/90ea0393284e83e961f199ea6cd03d13354f.pdf (finding that state-of-the-art systems for sentiment analysis in German achieve only around 60 percent accuracy in most cases, even when a system is trained and tested on the same corpus). -

32

Daniel Preotiuc-Pietro, Ye Liu, Daniel J. Hopkins, Lyle Ungar, “Beyond Binary Labels: Political Ideology Prediction of Twitter Users,” Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (2017), https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/P17–1068. -

33

Diana Maynard, Kalina Bontcheva, and Dominic Rout, “Challenges in Developing Opinion Mining Tools for Social Media,” Proceedings of @NLP can u tag #user_generated_content?! (2012), http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2012/workshops/21.LREC2012%20NLP4UGC%20Proceedings.pdf#page=20 (showing that the accuracy of language and sentiment identification decreases when tools are used to analyze tweets because tweets tend to have greater language variation, tend to be less grammatical than longer posts, contain unorthodox capitalizations, and make frequent use of emoticons, abbreviations, and hashtags); Joan Codina and Jordi Atserias, “What Is the Text of a Tweet?” Proceedings of @NLP can u tag #user_generated_content?! (2012), http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2012/workshops/21.LREC2012%20NLP4UGC%20Proceedings.pdf (arguing that the use of nonstandard language, emoticons, spelling errors, letter casing, unusual punctuation, and more makes applying natural language processing tools to user-generated social media content an unresolved issue); Dirk Von Grunigen et al., “Potential Limitations of Cross-Domain Sentiment Classification,” Proceedings of the Fifth International Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Social Media (2017), http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W17–1103 (finding that sentiment analysis tools trained for one domain performed poorly in other domains). See generally Will Knight, “AI’s Language Problem,” MIT Technology Review, August 9, 2016, https://www.technologyreview.com/s/602094/ais-language-problem/. -

34

Su Lin Blodgett and Brendan O’Connor, “Racial Disparity in Natural Language Processing: A Case Study of Social Media African-American English,” Proceedings of the Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency in Machine Learning Conference (2017): 2, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1707.00061.pdf. -

35

DHS, “DHS Transition Issue Paper: Screening and Vetting,” 1, in Strategic Issue Paper Summaries: Presidential Transition 2016–2017, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/TSA%20Presidential%20Transition%20Records.pdf#page=205 (“DHS is working to expand its current uses of social media to enhance existing vetting processes . . . [and] established a Social Media Task Force in December 2015 to examine current and potential uses of social media and how DHS could best expand its use”). -

36

George Joseph, “Extreme Digital Vetting of Visitors to the U.S. Moves Forward Under a New Name,” ProPublica, November 22, 2017, https://www.propublica.org/article/extreme-digital-vetting-of-visitors-to-the-u-s-moves-forward-under-a-new-name/a>.