Visitors to the Smithsonian in Washington can marvel at many artifacts that reflect our country’s story. One item on display changed the course of history itself: the “butterfly ballot” that Palm Beach County, Florida, used in the 2000 presidential election. In December of that year, the Supreme Court stopped the state’s recount, handing the presidency to George W. Bush.

But for that poorly designed ballot — and the resulting 5–4 decision — Al Gore would have become president. What’s more, Bush v. Gore changed the trajectory of election law and painted the Court in a partisan light like never before.

Bruce Weaver/Getty

Bruce Weaver/Getty

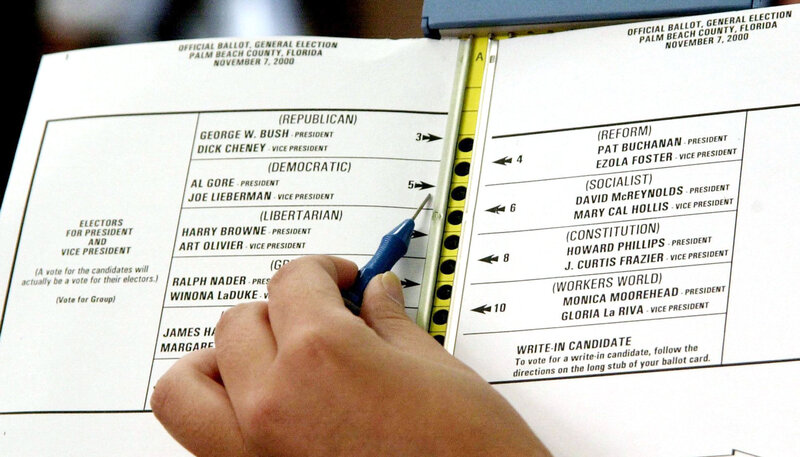

It all started with that infamous ballot. Presidential candidates from major and minor parties appeared on either side of a line of holes down the center of the ballot for voters to punch through with a stylus to indicate their pick. On the left, the first two names were Republican George W. Bush and Democrat Al Gore, but confusingly they corresponded to the first and third holes.

In addition to the layout problems was an issue with how the ballots recorded votes: Some voters punched cleanly through the card, while others left only dimples that election workers later examined with magnifying glasses to determine voter intent. Some ballots presented the issue of the “hanging chad,” where a piece of the ballot was left clinging by a corner or two. (The Smithsonian also has a bag of these.)

Studies indicate that at least 2,000 Palm Beach County voters accidentally selected Reform Party candidate Pat Buchanan when they meant to vote for Gore, who lost Florida — and therefore the Electoral College — by just 537 votes.

The Supreme Court’s opinion noted how the “controversy seems to revolve around ballot cards designed to be perforated by a stylus but which, either through error or deliberate omission, have not been perforated with sufficient precision for a machine to register the perforations.” That was true. But the majority created an unprecedented firestorm when it reversed the Florida Supreme Court’s decision to order a recount based on Florida election law, shutting down those efforts over concerns about a timely resolution of the election.

Two dissenting justices otherwise agreed that there were constitutional problems with differing standards used to determine voter intent given the poor ballot design, but they thought there was enough time to allow the recount to proceed. “The extraordinary setting of this case has obscured the ordinary principle that dictates its proper resolution,” wrote Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in dissent. “Federal courts defer to a state high court’s interpretations of the State’s own law.”

At the time, public trust in the Court had been relatively stable for decades. Approval was at 62 percent four months before Bush v. Gore, dipping only slightly thereafter but then rebounding for several years. Even after such a contentious and bitter postelection process, the Court had a well of public confidence to draw on that had not run dry. The peaceful transfer of power proceeded, and as vice president, Gore presided over the joint session of Congress that certified Bush as the Electoral College winner on January 6, 2001.

The seeds of skepticism had been planted, though. A partisan divide emerged between Republicans and Democrats after the decision, with 80 percent of Republicans viewing the Court favorably and 62 percent of Democrats doing so when Bush took office.

That gap has waxed and waned a bit over the following two decades. Two of President George W. Bush’s appointments to the Supreme Court in his second term played pivotal roles in gutting the Voting Rights Act, deregulating campaign finance law, and greenlighting partisan gerrymandering. Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which took away the constitutional right to abortion, widened it even further.

Today, the Court’s favorability ratings among Democrats have slipped to 26 percent while Republican favorability is at 71 percent. And a June 2025 survey found that only 20 percent of Americans now view the Court as “politically neutral,” with majorities of both Republicans and Democrats disagreeing.

The Florida recount crisis did, however, spur some constructive reform. It sparked passage of the bipartisan Help America Vote Act to set basic national standards for certain aspects of election administration, such as requiring voting systems to have certain features to improve recounts and audits, and the law made a host of improvements to voter registration processes.

More recently, after Trump supporters tried to overturn the 2020 election by exploiting vulnerabilities in a 135-year-old law that governs Electoral College proceedings, Congress passed the Electoral Count Reform Act and closed several loopholes to clarify vague components of the prior law. These critical steps strengthened the law governing how presidential elections are certified but did not eliminate the possibility of another disputed election reaching the Supreme Court.

If a battle over another razor-thin presidential election were to land on its doorstep, the Court would bear a heavy burden of convincing a deeply polarized public that its decision is based on the law and not politics. Justice John Paul Stevens’s dissent in Bush v. Gore remains prescient: “Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year’s presidential election, the identity of the loser is perfectly clear. It is the Nation’s confidence in the judge as an impartial guardian of the rule of law.”

Twenty-five years later, that warning resonates.