When the Supreme Court sits for oral argument on October 3 in Gill v. Whitford, the Justices will have the benefit of dozens of amicus (or friend-of-the-court) briefs that have been filed in support of the voters who challenged Wisconsin’s state assembly map.

When the Supreme Court sits for oral argument on October 3 in Gill v. Whitford, the Justices will have the benefit of dozens of amicus (or friend-of-the-court) briefs that have been filed in support of the voters who challenged Wisconsin’s state assembly map.

The subjects covered by the briefs run the gamut, from describing how gerrymandering is profoundly at odds with the Framers’ vision for our democracy to warning the Court about how cutting-edge technology and “Big Data” will make gerrymandering much worse in the future if the Court doesn’t step in. The filers of the briefs are equally diverse. Their ranks include prominent Republicans and Democrats, civil rights groups, citizens in the states affected by extreme gerrymandering, and leading legal scholars, historians, and political scientists.

Here are highlights from some of the key briefs:

Both Republicans and Democrats Say Fixing Extreme Gerrymandering Isn’t about Democrats vs. Republicans

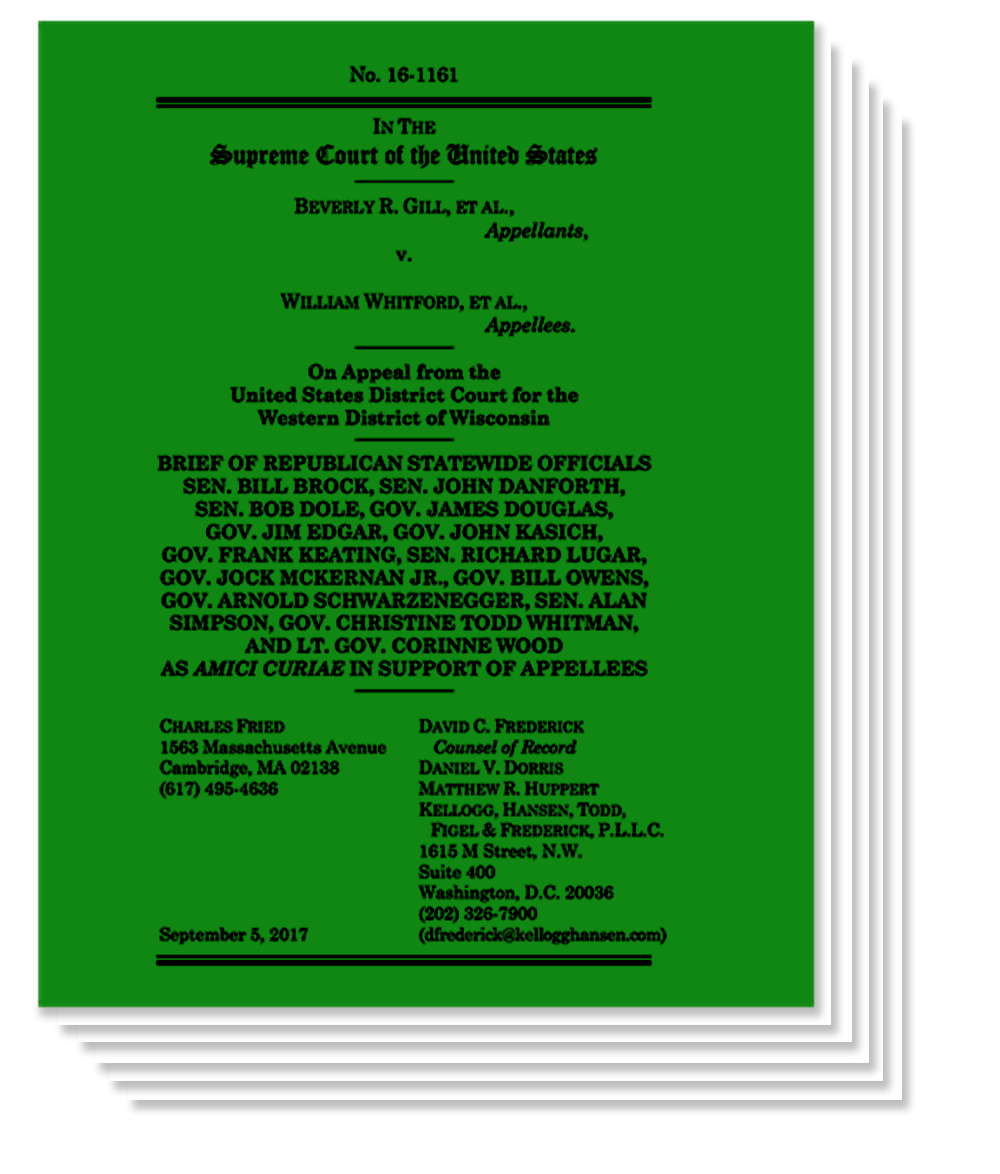

The briefs forcefully refute the familiar argument that partisan gerrymandering is mainly about whether Democrats or Republicans come out on top electorally. For example, a brief filed by prominent Republicans Arnold Schwarzenegger, John Kasich, Bob Dole, and Dick Lugar, among others, asserts that “[i]f th[e Supreme] Court does not stop partisan gerrymanders, partisan politicians will be emboldened to enact ever more egregious gerrymanders . . . That result would be devastating for our democracy.” Meanwhile, Senator John McCain—in a brief filed with Senator Whitehouse—warned that “[p]artisan gerrymandering has become a tool for powerful interests to distort the democratic process.” A bipartisan group of 65 current and former state lawmakers, and a bipartisan coalition of current and former members of Congress have also filed briefs in support of the plaintiffs.

What’s more, experts who have helped Republicans and Democrats draw maps in the past have come together to say that “the courts can, and should, play a role in policing improper partisan gerrymanders.”

The NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund and other civil rights groups also echo that gerrymandering isn’t just a political fight between the parties, powerfully reminding the Court that “[b]oth Democratic and Republican legislatures have used the power of the state to enact extreme partisan gerrymanders,” many “at least in part at the expense of minority voting rights.”

As these briefs make clear, when courts place limits on partisan gerrymandering, it is voters who win, not political parties.

The Problem of Extreme Gerrymandering is a Discrete and Manageable One

The briefs also provide important perspective on the challenge facing the Court by making clear that Whitford isn’t a referendum on all things that might be objectionable about redistricting and our legislatures.

Instead, as briefs such as the Brennan Center’s remind the Court, it’s about a relatively rare, but undoubtedly very serious, problem: “extreme partisan gerrymandering,” when one party “intentional[ly] manipulat[es] … the redistricting process to give itself a large majority in a legislature and to insulate that majority from future changes in voter preferences.” In an extreme partisan gerrymander, one party uses the redistricting process to entrench itself in power, engineering maps to give itself a majority—or even, in some cases, a supermajority—regardless of how voters actually vote.

This entrenchment theme is echoed by many of the briefs, from Republican statewide elected officials to the ACLU to leading historians. And, crucially, this problem doesn’t occur everywhere. By the Brennan Center’s estimates, it has reared its head in less than ten congressional maps this cycle, and perhaps a dozen or so state legislative maps in the same time period.

Extreme Partisan Gerrymandering Is a Real and Urgent Problem for Our Democracy – and about to Get Worse

But if extreme gerrymandering is rare, the briefs make clear that its effects are severe where it does occur and likely only to get worse if the courts don’t step in now to place some limits on how legislators can use partisanship to draw districts.

The briefs outline for the Court a staggering array of harms that extreme gerrymandering causes. A bipartisan group of 65 current and former state legislators notes that it undercuts incentives for legislators to collaborate and form bipartisan partnerships, breeding “distrust, dysfunction, and hostility” that spills over into legislative sessions.

The briefs also talk about the havoc extreme gerrymandering wreaks on the links between voters and their legislators. Civic organizations, democracy groups, and even elected officials themselves all emphasize that entrenchment undercuts legislators’ accountability to voters and the representativeness of legislatures. When maps are so carefully designed that they allow parties to maintain their hold on legislative power even with a minority of the vote, there’s no normal political solution to the problem.

Moreover—as leading constitutional law scholars, the ACLU, and others explain—extreme partisan gerrymanders override individual voters’ First Amendment rights of expression and association. As the constitutional law scholars demonstrate, partisan gerrymandering directly undercuts voters’ ability to band together in political parties to advance their common interests through the ballot.

And a brief by nearly twenty prominent political scientists warns that the recent explosion of voter data and advances in technology threatens to make “gerrymandering techniques that were only theoretical in the 2010 redistricting cycle … commonplace in the 2020 redistricting cycle and beyond.” Consequently, without some judge-made rules against partisan gerrymandering, “voters face a future of gerrymanders that are even more biased and more durable … than ever before.”

Partisan Gerrymandering Is Not a Time-Honored American Tradition

The briefs also offered important historical context for understanding gerrymandering. Gerrymanderers have long tried to justify their practices by arguing that politicians have been gerrymandering districts from very early on in the nation’s history. Wisconsin has offered the same defense in this case.

But, fifteen historians from leading universities told the Court that “any claim that partisan gerrymandering has been regarded as an acceptable characteristic of our democratic system is demonstrably ahistorical.” Indeed, “consistently since its inception, partisan gerrymandering has been forcefully denounced as unconstitutional, as a form of corruption that threatens American democracy, and as an infringement on voters’ rights.”

Extreme Partisan Gerrymandering Is Easy to Identify

Last but not least, if extreme gerrymandering is dire, the briefs assure the Court that judges have plenty of tools at their disposal to identify the worst maps.

A group of nearly twenty prominent social scientists explains that significant advances in the social sciences have produced a wealth of statistical and technological tools that make identifying gerrymanders easier and more reliable than ever before.

Many of these tools can help courts tell if maps have “partisan symmetry,” or, in other words, whether voters from each party have an equal opportunity to translate their votes into seats. As Yale Law School Dean Heather Gerken and a team of leading social scientists underscored for the Court, “Partisan symmetry is highly intuitive, deeply rooted in history, and accepted by virtually all social scientists.”

Although several different metrics for measuring partisan symmetry exist—including the “efficiency gap” measure that the plaintiffs used in Whitford to assess Wisconsin’s map—Gerken & Co. stress that “[u]nder any partisan-symmetry test, Wisconsin’s legislative districts are grossly asymmetrical.” This is important: Because Wisconsin’s map is wildly unbalanced by any measure, the Court doesn’t have to rely on the efficiency gap, or any other particular metric, to rule for the plaintiffs and can rest assured that the social science can help judges reliably identify the worst maps.

But it doesn’t stop with partisan symmetry. Courts can also use cutting-edge simulated mapping applications to smoke out the likely causes of partisan asymmetry. As a brief by political geography scholars who specialize in mapping applications explains, these applications illustrate that the asymmetry in Wisconsin’s electoral map is not the result of so-called “clustering”—the belief that Democrats huddle together in cities while Republicans spread out across the countryside.

And courts have more than top-notch social science at their disposal. The Brennan Center’s brief explains that “two straightforward, objective criteria … are highly correlated with” extreme gerrymanders: “single-party control of the redistricting process” and a “recent history of competitive statewide elections.” When these two factors are present, legislators have both “the motive and opportunity” to create an extreme gerrymander. These two factors alone would narrow down the range of potentially unconstitutional maps to just a handful this cycle.