Legislative Assaults on State Courts – 2018

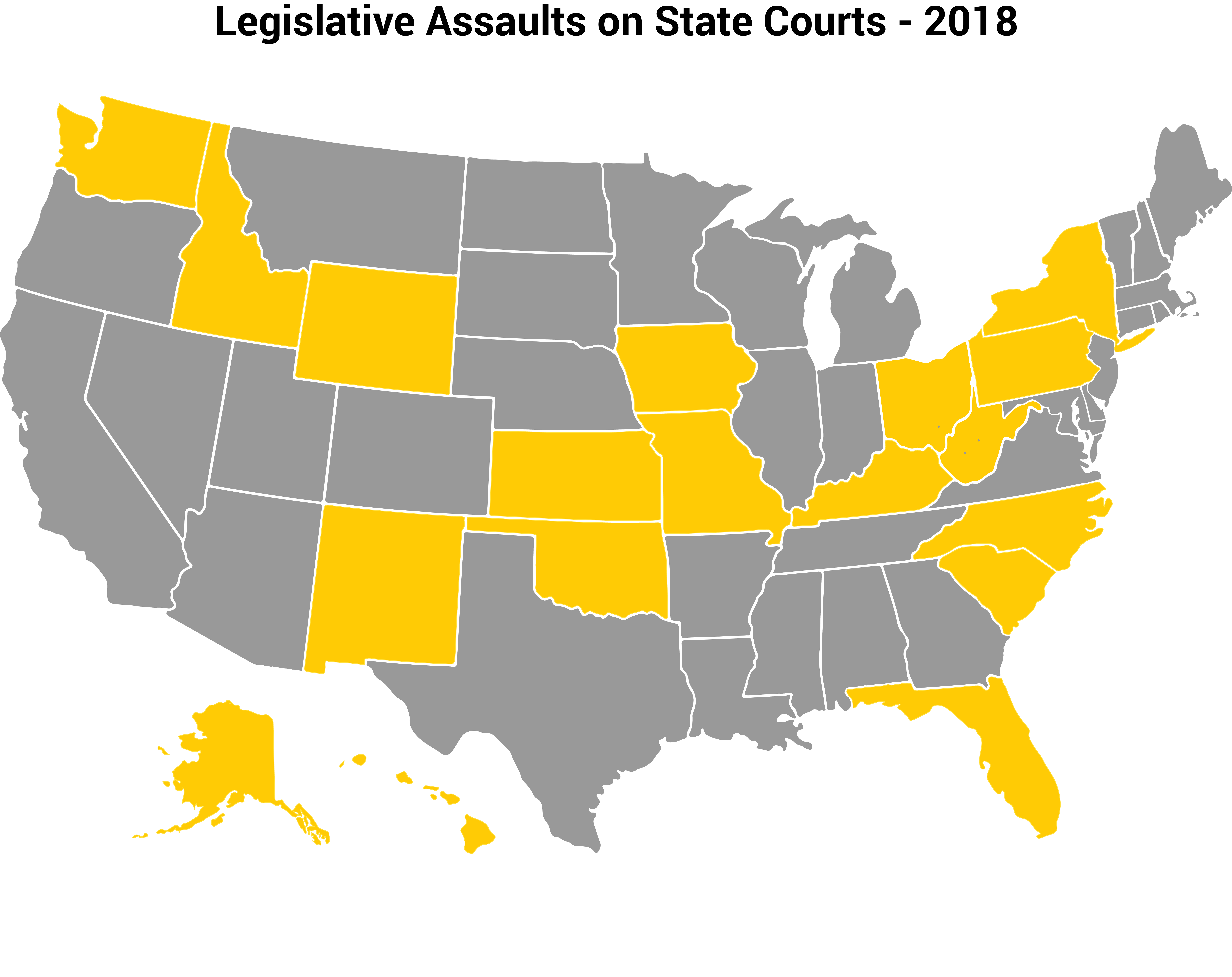

Legislatures in at least 18 states are considering legislation that would diminish the role or independence of the courts.

This post was updated on December 17, 2018. Read our summary of the findings.

In the Trump era, courts frequently appear to be the last line of defense against partisan overreach. But in many states, courts’ vital role in our democracy is under threat.

In our democratic system, judges serve as an independent check on the political branches, not a tool of the legislature or the governor. Courts are required to decide cases regardless of politics or external pressures, and to ensure that the other branches do not overstep their authority or encroach on individual rights.

Yet this year, legislators in at least 18 states considered at least 60 bills that would have diminished the role or independence of the judicial branch, or simply made it harder for judges to do their job — weakening the checks and balances that underlie our democratic system. To identify bills, the Brennan Center reviewed legislation identified by CQ StateTrack, provided by Piper Fund, media reports, and the National Center for State Court’s Gavel to Gavel website.

These bills threatened this balance of power in a variety of ways. Many sought to give the legislature or governor more power over judicial selection, often for partisan advantage; others gave the legislature the power to override court decisions and decide the constitutionality of laws they themselves wrote; still others exerted political, financial, or other pressures on courts to change the outcome of future cases.

In 2017, the Brennan Center documented several trends with respect to legislative assaults on the courts, including 45 bills introduced that year. In 2018, many of those trends continued, while new ones emerged.

In 2018, lawmakers in at least 18 states considered legislation that would have diminished the role or independence of the courts. This included brazen efforts to impeach justices in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, to give the legislature significant new authority over choosing judges in North Carolina, and to limit the state supreme court’s jurisdiction in Kansas:

- Twenty-seven bills in eight states would have injected more politics into how judges are selected

- Ten bills in seven states would have increased the likelihood of judges facing discipline or retribution for unpopular decisions, or would have politicized court rules or processes

- Six bills in three states would have cut judicial resources or established more political control over courts in exchange for resources

- Four bills in three states would have manipulated judicial terms, either immediately removing sitting judges or subjecting judges to more frequent political pressures

- Eleven bills in seven states would have restricted courts’ power to find legislative acts unconstitutional, or allowed the legislature to override court decisions

- Twelve bills advanced in significant ways in 2018, either passing favorably out of a committee or subcommittee, receiving a hearing, passing through one house of the legislature, or even going before voters as a constitutional amendment

Many of these efforts were concentrated in a handful of states. In two states, North Carolina and Oklahoma, numerous legislative proposals reflect a concerted effort by legislators to gain a partisan advantage in the courts. In North Carolina, these proposals followed Republicans’ loss of the governorship and a conservative majority on the state supreme court in 2016, while retaining a veto-proof legislative majority. In Oklahoma, bills followed high-profile rulings on the death penalty, abortion, and religion that ran against the state’s conservative politics. They continue a trend in the state which saw 15 bills to change how judges are selected in 2016 alone.

In Pennsylvania and Kansas, impeachment and jurisdiction-stripping proposals were introduced in direct response to individual court rulings interpreting the states’ constitutions. In Pennsylvania, the Supreme Court ruled in January that the state’s congressional map was an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander, prompting an impeachment effort. In Kansas, proposals to limit judicial jurisdiction over matters of public education funding came as the legislature faced a court-imposed deadline to fulfil its constitutional obligation to sufficiently fund the public education system.

Finally, in Iowa, a dispute between the Legislature and judiciary over allowing guns in courthouses at least partially fueled a number of proposals.

And, while these states may be the locus of anti-court legislation, legislative threats to courts can be seen across the country. These bills aim to:

Change Judicial Selection Systems: In eight states, 27 bills would have changed how judges are selected. In most cases, the result would have been to inject more politics into the selection process. States use a variety of methods to select judges, but the practices that best preserve judicial independence and integrity are those that insulate judges from the constant political and partisan pressures that other branches face. To this end, many states use nonpartisan judicial nominating commissions to vet and recommend judges for appointment. But a new legislative trend this year would keep those commissions in name while significantly shrinking their role.

Add politics to the selection process

- In Florida (HB 753, SB 1030) and Oklahoma (SB 700), bills would have taken away the ability of state bar associations to appoint members to the states’ judicial nominating commissions. Instead, both state legislatures proposed to give themselves the power to nominate or appoint those commissioners. In Iowa (SF 327), a bill would have left the bar’s representatives on the commission, but made them “nonvoting, advisory” members.

- In Hawaii (SB 673, HB 2563/SB 3039), proposed constitutional amendments would have required Senate confirmation of sitting judges’ reappointment. Currently Hawaii’s Judicial Selection Commission makes those decisions, but this proposal would have effectively given the Senate veto power over a process regarded as effective at insulating judges from political pressure.

- In Oklahoma (SJR 42), a proposed constitutional amendment, would have required that any election for the state’s appellate courts be partisan. Currently, Oklahoma appellate judges take part only in nonpartisan retention elections. In 2016 and 2017, North Carolina made a similar change, converting both Supreme Court and lower court elections to partisan races.

- Another proposed constitutional amendment in Oklahoma (SJR 14) would have required sitting judges standing for retention elections to attain 60 percent of the vote, rather than the current 50 percent of the vote. In 2016, four judges on Oklahoma’s highest courts stood for retention — two held their seats with less than 60 percent, and the other two won with less than 61.5 percent of the vote. The need to win a supermajority of the public’s support could make Oklahoma’s judges more reluctant to make controversial rulings.

- A bill in Oklahoma (SB 971), a conservative state with a majority of its Supreme Court appointed by former Democratic governors, would have required that the appointing governor’s name appear next to a candidate’s name when they stand for retention election. The proposal would have also required the ballot to show the age of the judge and the number of years the judge has served.

Weaken or eliminate nonpartisan judicial nominating commissions

- In Missouri (SJR 28), Oklahoma (SJR 43), and South Carolina (H 3204, H 3207, H 4043), proposed legislation would have left selection commissions in place, but significantly limited their role in the appointment process. Currently the commissions in those states recommend three candidates to the Governor, or to the Legislature in the case of South Carolina, to choose from for appointment. These bills would have required that commissions put forward every “qualified” applicant, substantially curtailing the commission’s role. Legislators in North Carolina floated a similar proposal this year.

- In Iowa (HJR 6, HJR 2004) and Missouri (HJR 47), proposed constitutional amendments would have eliminated the states’ judicial selection commissions, giving governors in those states the power to appoint judges without vetting by a commission.

Create a partisan advantage in judicial selection

- In North Carolina, the legislature placed a constitutional amendment before voters (H 3) to require the governor to select judges to fill interim vacancies from a list created by the legislature. Voters ultimately rejected the proposal which included a nominal role for a nominating commission. Two other bills (H 240, H 241) would have similarly transferred to the General Assembly (the state’s legislature) the governor’s current authority to appoint judges to fill interim district court vacancies and appoint special superior court judges. Another bill (H 335) would have required the governor, when filling a vacancy on the Supreme Court, Court of Appeals, or a superior court, to select from a list provided by the leaders of the political party of the vacating judge. These bills were introduced by Republicans in the General Assembly after a Democrat was elected governor.

- A bill in North Carolina (H 717) to redraw district court and superior court judicial districts would have disproportionately harmed voters of color and Democratic voters, amounting to judicial gerrymandering, according to analyses by NC Policy Watch and the Southern Coalition for Social Justice. Over-riding the governor’s veto, the Legislature passed a version of H 717 that redistricted only portions of the state, along with another bill (S 757) which redistricted several populous counties. Another bill (H 677) would have then added district court judges to the three-judge panels which, in North Carolina, hear high-stakes cases related to redistricting and challenges to the constitutionality of legislative acts.

- Proposed constitutional amendments in Pennsylvania (HB 829, SJR 1144, SJR 22) would have had voters elect Supreme Court justices by seven districts of equal population, rather than statewide. While districted elections are not necessarily harmful, they can open the door to gerrymandering and other partisan gamesmanship. HB 829 was introduced by a Republican legislator without explanation following an election in which Democrats gained a majority of seats on the state Supreme Court.

Politicize Judicial Rulings, Discipline, or Court Rules: Seven states considered legislation that would have put undesirable political pressure on judicial decisionmaking. Judges must be able to decide cases without fear of retribution, but some of these bills would increase the likelihood of a judge losing their job for making an unpopular ruling. Other proposals would empower politicians to alter court procedures for reasons other than fair and efficient decisionmaking.

- A bill in Alaska (HB 251) would have added “exercising legislative power” as grounds for judicial impeachment, and would have expressly exempted a finding of this kind of malfeasance from judicial review. This language is similar to a Kansas bill that failed to make it through the legislature in the 2015–2016 session. That bill provided that Supreme Court justices could be impeached for “attempting to usurp the power of the legislative or executive branch of government.”

- In Pennsylvania, twelve legislators co-sponsored resolutions (HR 766, HR 767, HR 768, HR 769) calling for the impeachment of four sitting Supreme Court justices. The resolutions were a response to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s decision striking down the state’s congressional map as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. The court’s decision likely cost Republicans seats in the 2018 election, and all twelve co-sponsors were Republicans.

- In West Virginia, the House voted (HR 202) to impeach the four justices that had not yet resigned in the wake of a scandal over use of state resources. While the allegations against some justices were troubling, the timing of the impeachment betrayed legislators’ goal of using the scandal to gain a political advantage on the court by clearing the bench and giving the conservative governor the ability to appoint multiple justices. Ultimately, two of the impeached justices managed to keep their seats on the court while the other two resigned their positions before their trial in the Senate.

- A pair of bills in Washington (HB 2636/SB 6405) would have required the state’s Office of Financial Management to produce, and issue by press release, a “fiscal note” estimating the costs of Washington Supreme Court decisions with a budgetary impact above $500,000. These bills were introduced in the middle of a prolonged battle between the court and the legislature resulting from a 2012 court decision finding that the state was inadequately funding its education system.

- A proposed constitutional amendment in New Mexico (HJR 6) would have transferred the power to set court rules and procedures from the judicial branch to the legislature. A similar proposal will appear on Arkansas’s ballot this November. Arkansas’s Legislature voted to put before voters a constitutional amendment which would, in addition to capping damages and attorney’s fees in certain lawsuits, allow the Legislature to override the Arkansas Supreme Court’s rules by a three-fifths vote.

- Bills in Idaho (HB 419) and Kentucky (SB 229) would have deemed a court ruling unenforceable if it relied in part on foreign law. This legislation is part of a national trend of bills put forward by anti-Muslim groups aimed at prohibiting Sharia law from being considered in state courts. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, 14 states have enacted such legislation since 2010. HB 419 passed the Idaho House.

Reduce or Control Court Resources: Three states would have significantly reduced judicial branch resources, or demanded increased control over the judicial branch in exchange for resources. When legislators threaten to cut judicial funding unless judges adhere to the legislature’s wishes, it violates the separation of powers principles that our democracy relies on. And actual losses of funding or resources have forced courts to close or led to case backlogs, making it harder to access justice.

- A bill in North Carolina (S 617) would have largely eliminated “emergency judges,” which lower courts had previously relied on to help alleviate backlogs. Last year, restrictions on the use of these judges forced courts to cancel court sessions.

- A series of bills in Iowa (SF 2044, SF 2052, SF 2104, HF 2036) responded to Iowa Chief Justice Mark Cady’s directive that the judicial branch would continue to enforce a courthouse weapons ban despite a new Iowa law allowing guns in courthouses. One proposal provided that, if an Iowa court enforces a weapons ban, the court must pay rent to the state and must pay for an armed security guard using funds from the chief judge’s salary. Two other bills would have expressly allowed persons to carry weapons in courthouses, regardless of any court prohibitions. Another would have reduced Supreme Court justice’s salaries to $25,000, an approximately 85 percent pay cut. The sponsor of the judicial salary bill said, “If the Supreme Court wants to act like legislators they need to start getting paid like legislators.” Iowa’s part-time legislators make $25,000 annually.

- A bill in New York (A 09505) would have, in exchange for giving the judicial branch an additional 0.5 percent budget increase, required that judges file monthly certifications that they worked for at least 8 hours on each workday of the preceding month. The bill would have also required periodic audits of judicial salaries and operating expenses by the state comptroller.

Alter Judicial Term Lengths and Limits: Proposals in three states would have altered judicial terms of office, expediting the removal of sitting judges and increasing the frequency of judicial elections. The shorter a judge’s term length, the greater the pressure that judge will feel to rule with electoral or political, rather than legal, considerations in mind. And, while term limits can be beneficial, judges must be allowed sufficient time to serve and should not be removed from the bench for partisan reasons.

- In North Carolina (S 698), where judges are elected in newly-partisan races, a bill would have reduced all judicial terms to two years, subjecting judges to perpetual campaigns and magnifying the reselection pressures judges already face. One legislator supporting the bill said, of judges, “if you’re going to act like a legislator, perhaps you should run like one.”

- In Iowa (HJR 2002), where appointed judges retain their seats via non-partisan retention elections, a proposed amendment to the constitution would have cut Supreme Court justices’ terms in half from eight years to four years.

- Another proposed constitutional amendment in Iowa (HJR 2001) would have maintained Supreme Court justices’ current eight-year terms, but limited justices to a single term. More than half the current justices, including all justices appointed by a Democratic governor, have served for more than eight years.

- A bill in Oklahoma (SB 699) would have required appellate judges and justices to retire when the sum of their years of judicial service and their age equals 80 years. If implemented, this bill would require the retirement of seven members of the nine-member Oklahoma Supreme Court.

Shield the Legislature from Court Rulings: Proposals in seven states would have made it more difficult, or impossible, for either state or federal courts to rule a legislative act unconstitutional. These bills undermine one of the core responsibilities of state courts, which is to ensure that the two other branches are adhering to the states’ constitution. Two would have put legislators’ interpretation of the United States Constitution above that of the United States Supreme Court.

- Bills in Iowa (HF 2106/SF 2153/SF 2282) would have prohibited the Iowa Supreme Court from finding a state law unconstitutional, unless a supermajority of justices — 5 of 7 — agreed. Currently, only 4 justices need to agree that a law is unconstitutional.

- A bill in Washington (HB 1072) would have allowed the Legislature to override, with a simple majority vote, any decision by a Washington court striking down a legislative act as unconstitutional.

- A bill in Idaho (HB 461) would have allowed the Legislature to declare a decision of any federal court, including the United States Supreme Court, unconstitutional. If the Legislature declared a decision unconstitutional, no Idaho official could enforce that decision. This bill was voted down in the House on February 19, 2018.

- Two proposed constitutional amendments in Kansas would have prohibited the judicial branch from fully enforcing the Kansas constitution’s requirement that the legislature provide for the education of its residents. Following a Kansas Supreme Court ruling that Kansas’s public school system is inadequately funded, the Legislature faced an April 30 deadline to provide additional funding or face the potential that the courts will close schools. One proposed amendment, SCR 1609, would have prohibited the judicial branch from closing school districts, while HCR 5029 would have potentially removed education funding questions from the court’s jurisdiction entirely by prohibiting any court from determining the amount of funding needed to satisfy the state constitution. Possibly anticipating a similar dispute, a proposed constitutional amendment in Wyoming (SJR 4) provided that while the judiciary may declare that insufficient public school funding violates the state constitution, a court cannot command that the Legislature take any remedial action.

- A proposed constitutional amendment in Missouri (HJR 92/HJR 94) would have allowed Missouri voters to vote on whether federal laws are constitutional. If the voters decided a federal law was unconstitutional, Missouri courts would have been prohibited from enforcing that law, and stripped of jurisdiction over any cases involving that law or any similar state law.

- A House Memorial in Florida (HM 137) asked the United States Congress to propose a constitutional amendment providing that Congress and state legislatures may overrule, by a 60 percent vote, court decisions striking down federal or state laws.

Change Size of Courts: Court packing and court shrinking, adding or removing seats from a court is another way for legislatures or governors to gain a partisan advantage in their state’s courts. In recent history, Georgia and Arizona added seats to their state supreme courts to do just that. But removing sitting justices from the bench can have a similar impact.

- In Oklahoma (HB 1699), a bill would have reduced the number of justices on the state Supreme Court from nine to five. The bill’s formula for determining which current justices retain their seats would most likely have resulted in changed ideological control of the court within two years.

Firearms in Courtrooms: Courts have also been pulled into broader debates about gun rights in public spaces. In addition to the Iowa Legislature’s response to the Chief Justice’s efforts to limit guns in courthouses, at least one state considered a bill that would make it easier to bring guns into courthouses or courtrooms.

-

In Ohio(HB 622), a bill would have authorized a judge or magistrate who is a concealed handgun licensee to carry a weapon in the courtroom.

Image: Eric Thayer / Getty