Voter Suppression Has Gone Digital

The public should be able to tell where these messages are coming from and how they are being targeted

This month’s elections were fought online to an unprecedented degree, with an estimated $900 million in digital ad spending — more than two and a half times the 2014 midterms. Not all of this spending was intended to persuade voters to favor one side or the other, however. Some online activity tried to keep people from voting altogether. My research team at the University of Wisconsin-Madison found hundreds of messages on Facebook and Twitter aimed at voter suppression — designed to discourage or prevent people from voting.

Online voter suppression in 2018 showed similarities to Russia’s interference in the 2016 presidential election. We found three categories of messages: deception about how or when to vote, calls to boycott the election, and attempts to threaten or intimidate potential voters.

Voter suppression messages appeared online despite the platforms’ efforts to stop them. In October, Facebook broadened its election integrity policies to combat voter suppression and committed to taking down such content. Just a few days prior to Election Day, Reuters reported that Twitter also purged more than 10,000 automated accounts that discouraged voting. Clearly, the problem has not yet been solved.

Has Voter Suppression Gone Digital?

Voter suppression has been taking place in various forms over the years. Piven and colleagues demonstrate that voter suppression tactics took the form of blatant violence and intimidation in the Reconstruction era but have since transformed into regulatory devices such as voter ID laws and racial gerrymandering. More recently, voter suppression takes the form of misinformation campaigns and deceptive practices such as lying about the time, place, and manner of voting.

Deceptive practices have traditionally been comprised of fliers and phone calls. Now voter suppression has truly gone digital. In the 2016 elections, my research team found that the Internet Research Agency, a Kremlin-linked, information campaign operation, ran paid Facebook ads to suppress the turnout of nonwhite voters, especially African Americans. The night before Election Day, ads appeared urging people to “boycott the election” because neither of the presidential candidates would serve black voters. The ads, sponsored by the Russian-backed duo Williams & Kalvin, specifically targeted African American voters. In another study, my team found that voter suppression ads targeting nonwhites residing in minority counties (counties where the proportion of nonwhites is more than 50 percent of the population) in battleground states (where 2016 vote margins were less than +/- 5 percent) were eight times larger than that of their counterparts. Consistent with the findings from our prior research, most of the voter suppression ads were sponsored by groups that had not registered with the FEC and publicly shared no information about who they were.

Voter Suppression in the 2018 Midterms

My team monitored the midterm elections in real time over the past several weeks by utilizing publicly accessible Facebook ads and Twitter. Unlike our 2016 digital ad tracking and analysis, which was based on large scale, consented-user-based tracking independent from digital platforms (we collected 87 million ads exposed to 17,000 users who represented the U.S. voting age population), the information provided here is anecdotal. As Facebook and Twitter proactively removed voter suppression messages in real time, the data provided by the digital platforms do not include posts or accounts that were taken down. Still, we found noticeable voter suppression campaigns online, especially on Twitter.

We specifically focused on three types of voter suppression campaigns: deception (lying about the time, place, and manner of voting); calls for boycott; and voter intimidation or threats.

Deception

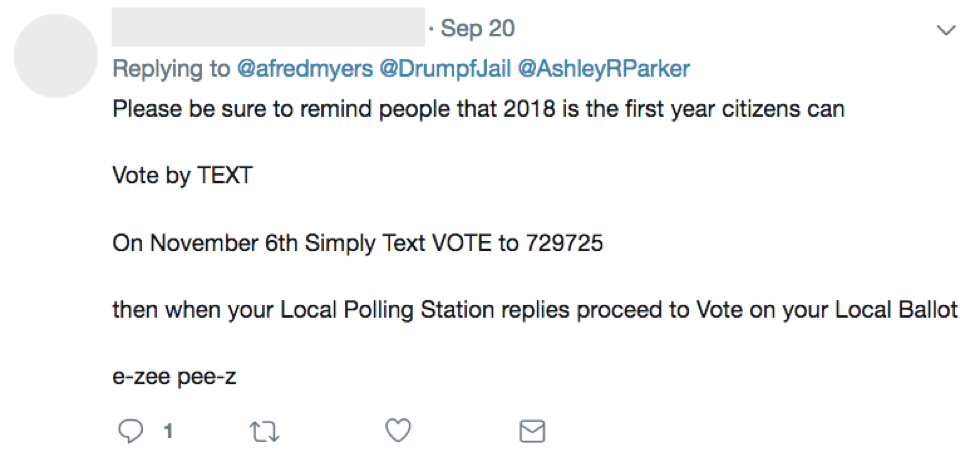

The provision of incorrect information about the election date was very common in unpaid posts on Twitter. Similar to Russian tactics reported in our previous study, some tweets encouraged people (more specifically, anti-Trump voters) to vote via text.

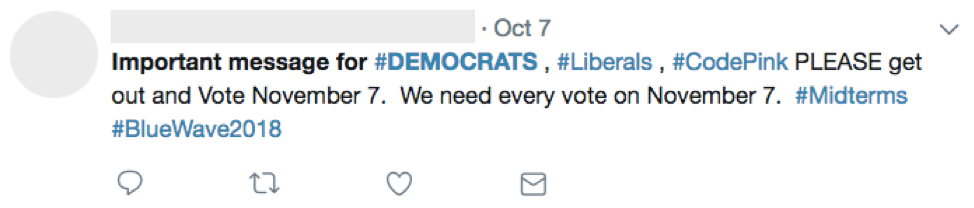

Especially, #votenovember7th, a hashtag that mobilized turnout but with incorrect election date information, was often paired with other hashtags designed for partisan mobilization such as #bluewave, #redwave, and such. We do not yet know who these users spreading misinformation were exactly.

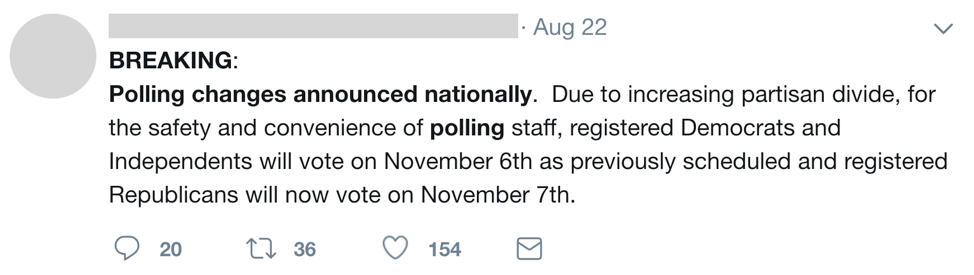

Many messages provided two different election dates — the correct one for their own party but the incorrect one for the opposing party. This type of message was tweeted by supporters of both parties.

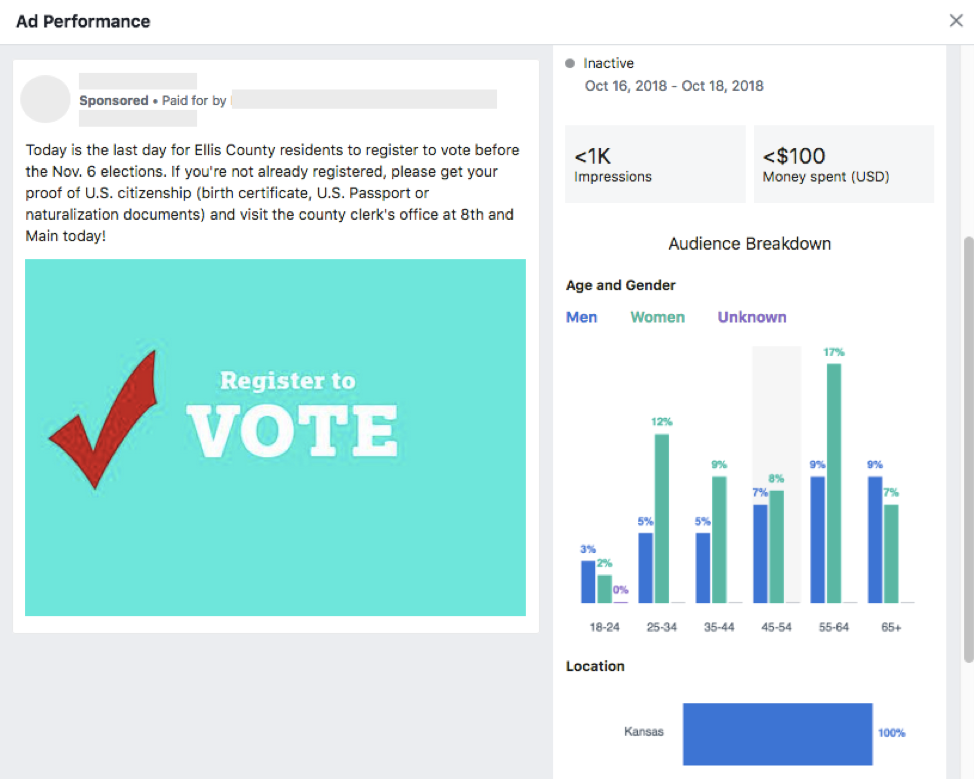

We did not find many paid ads containing incorrect information about the time, place, and manner of voting on Facebook. However, one ad targeting Kansas is worth noting. The ad indicated that voters would need a birth certificate or naturalization document to register. However, over the summer a court struck down the law requiring proof of citizenship. The ad was sponsored by a Republican candidate and primarily targeted women.

While many of these messages might have been circulated with innocuous intent, they are still worrying. Given the amplification potential of social media messages, they may confuse a large number of voters.

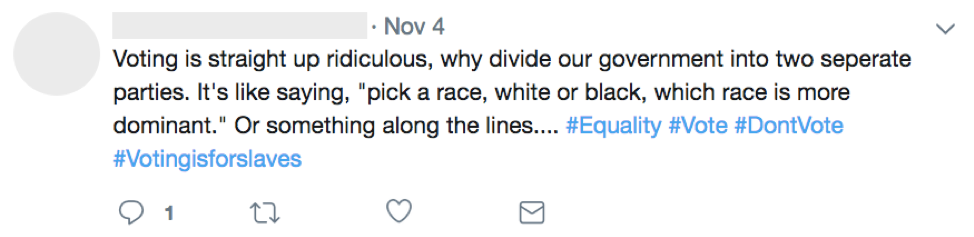

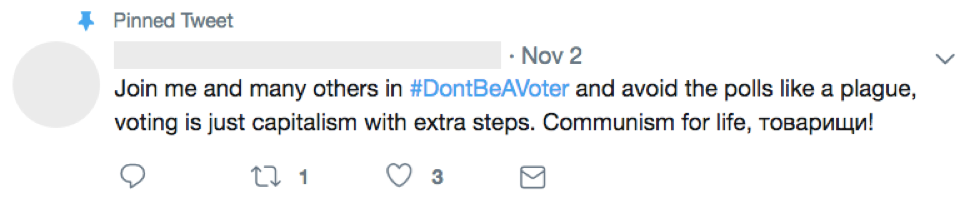

Demobilization and Calls to Boycott

We also found some voter suppression attempts to deter people from voting by saying that voting is pointless or that there is no difference between the parties. Many messages used hashtags like #dontvote and #dontbeavoter.

While the targeting of these calls to boycott was unclear in most cases (due to the limited information we have), some of the messages clearly targeted Latino and African American voters.

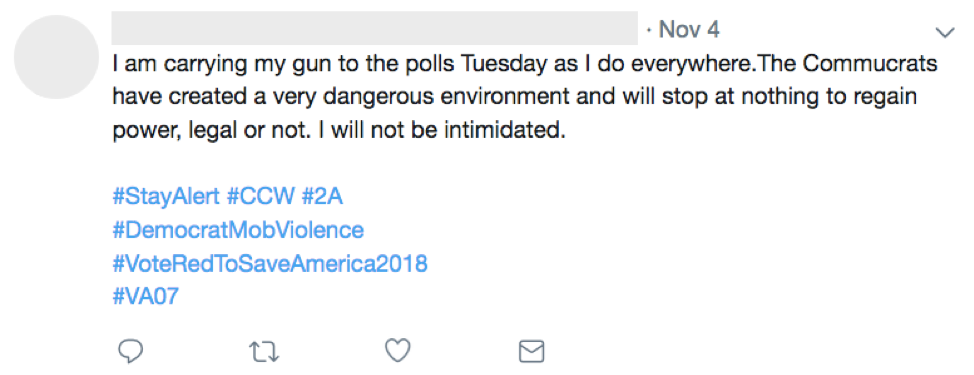

Voter Intimidation

In the 2018 elections, we found voter intimidation and threats attempting to organize violence at polling places.

After Nancy Pelosi’s mention of “collateral damage” on October 18, 2018, a Twitter user named “IllegalAlien” said, “if you are GOP, be SURE to BRING YOUR GUNS TO THE POLLS. Let’s show COLLATERAL DAMAGE.” This tweet itself did not have much traction.

However, after October 25, when the Nation Rifle Association’s spokesperson said on NRATV that gun supporters would need to bring guns to the polls to protect themselves from left wing mobs, tweets suggesting that NRA members or Republicans need to bring guns to the polls started trending.

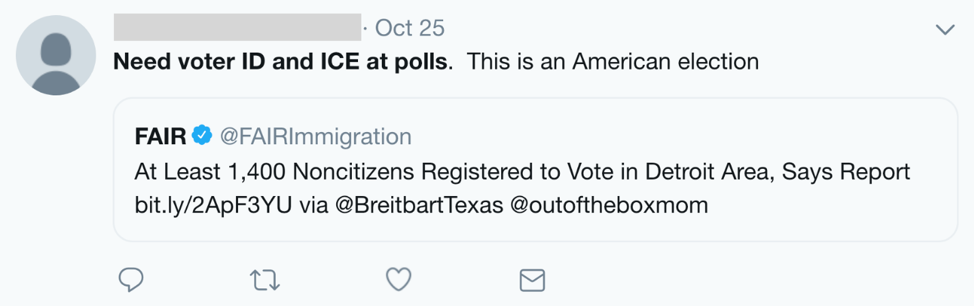

Voter intimidation messages were often paired with misinformation about voter fraud. We found many conspiratorial messages; for example, that George Soros organized migrant caravans to rig the election, and that ICE was showing up at the polls to deport immigrants.

What Should We Do?

In both the 2016 and 2018 elections, my research team has been observing various forms of voter suppression campaigns take place on digital platforms. Despite tech platforms’ proactive measures for combating voter suppression in the 2018 midterms, voter suppression messages still appear to be spreading rapidly.

Tech platforms’ voluntary, self-regulatory policies combating voter suppression are a very important first step. However, we need to consider consistent and systematic regulations to effectively address voter suppression campaigns. The policy response should be two-pronged: Deception about how to vote should be banned, and other messages about voting should be transparent.

First, Congress should explicitly define and prohibit deceptive practices like spreading false information about how or when to vote in order to keep people from voting. Although much of this type of conduct is already illegal, we need a federal law to clearly and comprehensively address it. The Deceptive Practices and Voter Intimidation Act, introduced this year in Congress, would accomplish this.

Second, online messages about voting and elections should be more transparent. The public should be able to tell where these messages are coming from and how they are being targeted. As my research has shown, most voter suppression campaigns online were sponsored by undisclosed groups. And demobilization frequently targets specific segments of the population in terms of race, gender, and income, potentially leading to discriminatory effects. Disclosure would discourage some from engaging in voter suppression and give the government, journalists, and civil society the chance to respond and counter suppressive messages. Before 2020, Congress should enact legislation that would provide clear, consistent guides for disclosure to address the issues described here.

(Image: Shutterstock.com)